Evolutionary Revolutionary Rotodyne

The Fairey Rotodyne still holds the world speed record for convertiplanes. It was a superb aircraft, with enormous potential. At one stage the order book was overflowing, but the project was killed off by managerial ineptitude and dithering.

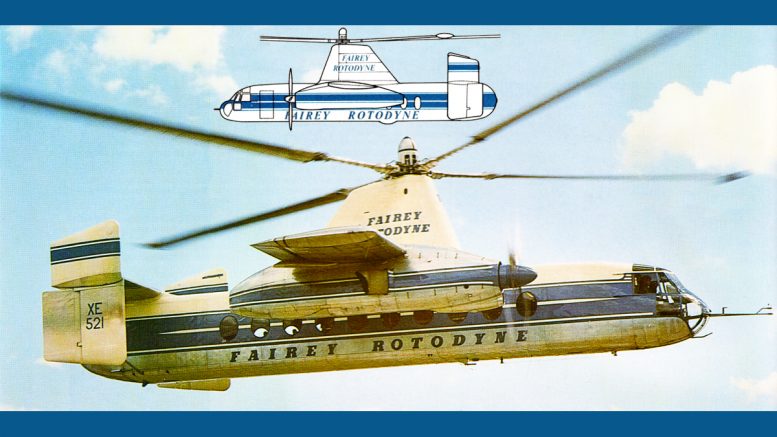

On 16 June 1959 a group of passengers boarded a turboprop airliner at London’s Heathrow airport and took off to fly to the Paris Air Show. Nothing particularly odd about that, except for one thing – this turboprop airliner was a helicopter.

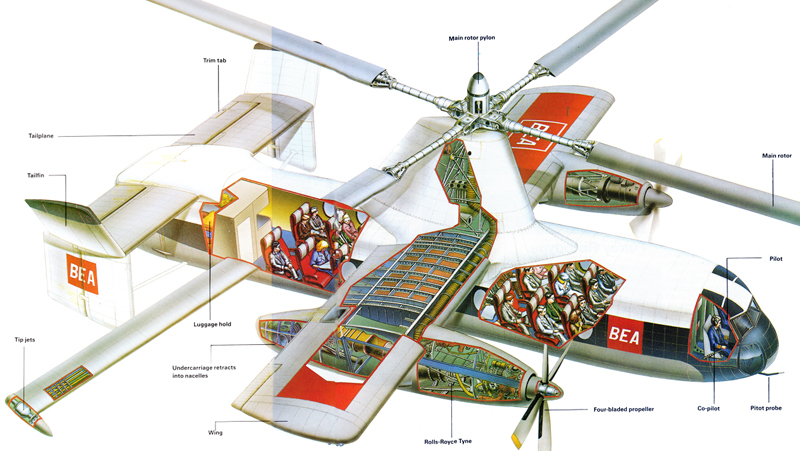

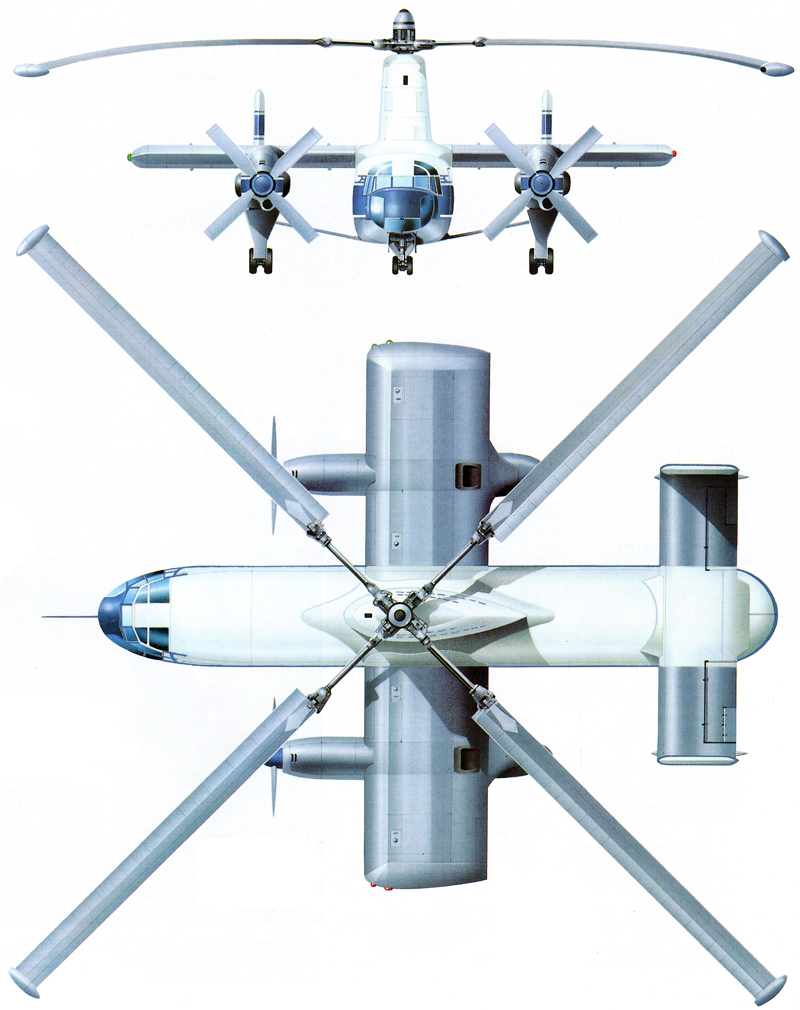

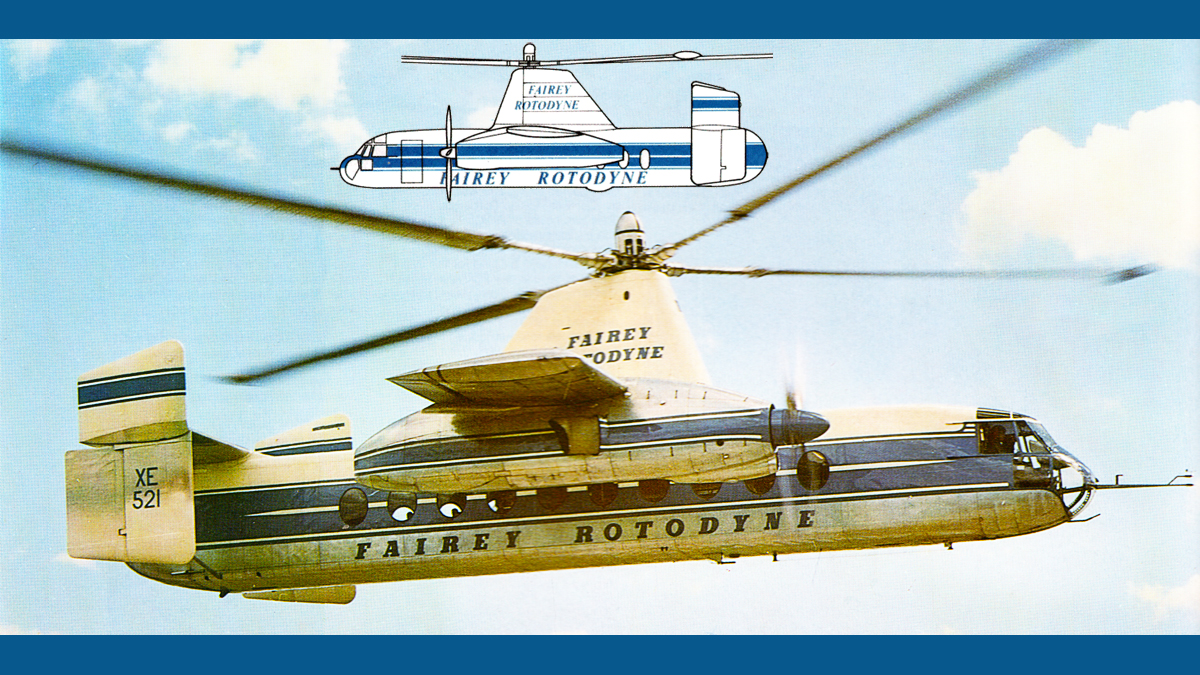

Inside the Rotodyne – The production version of the Fairey Rotodyne, dubbed Rotodyne Z, was to have had 10ft greater wingspan, with tapered outer panels, more powerful ailerons and four tailfins. New, more powerful engines would have been fitted, giving the production Rotodyne an even better performance and improved load-carrying capability.

It did not need to take off from Heathrow; in theory it could have taken off with 40 passengers from any small open space in the middle of London. It was, of course, the Fairey Rotodyne, the first aircraft ever built that combined VTOL capability with a capacious airline fuselage and conventional turboprop engines, a wing and a tail.

In fact it was not a simple helicopter, but a compound helicopter or convertiplane. It was evident as early as the 1930s that simple helicopters suffer from the fact that they rely totally upon their main rotor for lift and for propulsion. A rotor is less efficient than a wing in lifting the aircraft, but it is a necessary evil if you want VTOL.

Fairey Rotodyne – Gyrodyne

In cruising flight, however, it is nonsensical. It is an inefficient lifting system, an exceedingly inefficient propulsion system and a barrier to high speed, because of the excessive stalling angles reached by the retreating blade. The faster the helicopter goes, the worse the problem is, and it was clear that ordinary helicopters would be hard-pressed to reach 200 mph.

Only one Rotodyne was b

and it was unceremoniously

scrapped after the program ground to a close.

At the end of World War II Dr J. A. J. Bennett joined Fairey Aviation with a design for a neat helicopter, the Gyrodyne. The torque needed to drive the main rotor had to be reacted by an auxiliary rotor, and instead of being put at the tail this was put on the tip of the starboard wing, small wings being added to carry some of the lift in cruising flight.

Thus, while reacting the main-rotor drive torque, the auxiliary rotor served as a propeller, giving efficient forward thrust. In June 1948 the Gyrodyne set a world helicopter speed record at 125mph.

The Fairey helicopter team grew rapidly in strength, leaders being Dr G. S. Hislop, chief designer, and Captain A. G. Forsyth. Together with Bennett he schemed a compound helicopter which would combine the advantages of a helicopter’s VTOL capability with the advantages of an ordinary turboprop airliner in cruising flight.

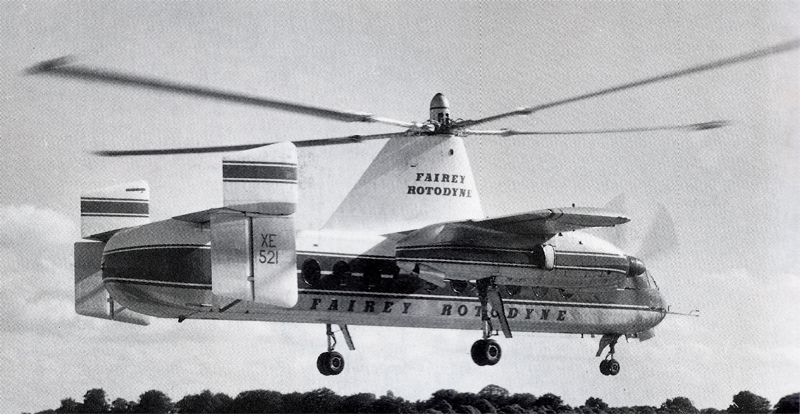

The Rotodyne appealed to military and civil customers. Here the prototype is seen lifting a girder bridge. Because the massive rotor could be driven by tip jets, and not freewheeling like that of an autogyro, the aircraft could hover.

To take off, the engines would drive powerful air compressors, which would pump air up to the rotor hub and along the hollow blades to pressure jets at the tips.

These pressure jets were fed with the compressed air and with fuel, similarly supplied along the blades. Each jet unit was very compact, causing only a small blister at the tip of the blade. The rotor could be started simply by blowing the compressed air.

Then, when the fuel was added and ignited, the rotor power was increased tremendously. By pulling up the collective pitch lever the helicopter could take off vertically.

It could then do what no aircraft had done previously: transition into forward flight, propelled by two pusher propellers on the tips of a small wing and lifted partly by the wing and partly by the freely windmilling rotor.

The Rotodyne showed enormous potential, offering helicopter like VTOL capability combined with speeds nudging 200mph.

The scheme was investigated by the Jet Gyrodyne, which made its first transition on 1 March 1955. Back in 1949 Bennett and Forsyth had schemed a big compound helicopter using this principle.

Three of the many apparent advantages were that the rotor was not driven by shaft power, so no bulky and heavy gearbox was needed, nor any anti – torque rotor; the wing unloaded the rotor in cruising flight, thus postponing the blade stall problem and making possible higher speeds; and propulsion was always by propellers.

Fairey Rotodyne VTOL airliner

Project designs proliferated, using such engines as the Alvis Leonides and Leonides Major, de Havilland H.7 shaft – turbines, Rolls-Royce Darts and Armstrong Siddeley Mambas.

But in December 1951 British European Airways, a bold promoter of new technology, issued a specification for a BEAline Bus, a helicopter able to carry 30 to 40 passengers at something like normal fares and still make a profit.

Today few airlines have any interest in serving city centers, but in 1951 the helicopter seemed to be maturing fast, and this far-sighted specification was hoped to lead fairly quickly to a true VTOL airliner.

By this time Fairey had done a lot of work on the compound helicopter idea, and in 1953 the company received a Ministry contract for a prototype to be called the Rotodyne. Numerous test rigs were built at the Hayes factory, at the White Waltham test airfield and at Boscombe Down.

Fairey Rotodyne Tip jets

The tip jets were actually known as Fairey High Pressure Combustion Chambers.

This last establishment was the location for what was virtually a complete Rotodyne, but initially with just one engine, propeller and pair of blades.

Later a second engine and pair of operative blades were added. The aircraft itself was assembled at White Waltham in summer 1957 and put through exhaustive static tests, one result of which was to show that in a single situation resonance could occur.

Fairey Rotodyne Main rotor

The four-bladed main rotor could autorotate, like that of an autogyro, during normal cruising speed, or could be driven by gas pressure jets for hovering, vertical take off or landing. The gas generator was based on the Rolls-Royce RB.162 lightweight lift jet.

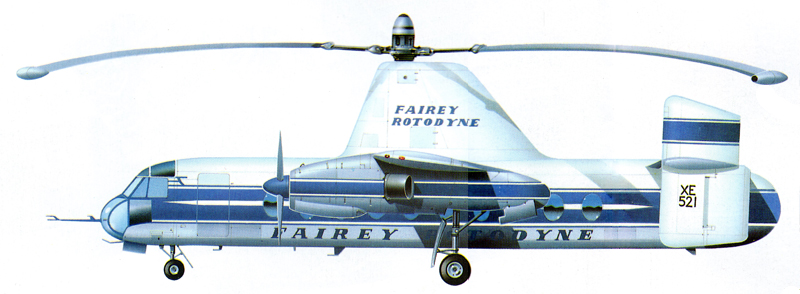

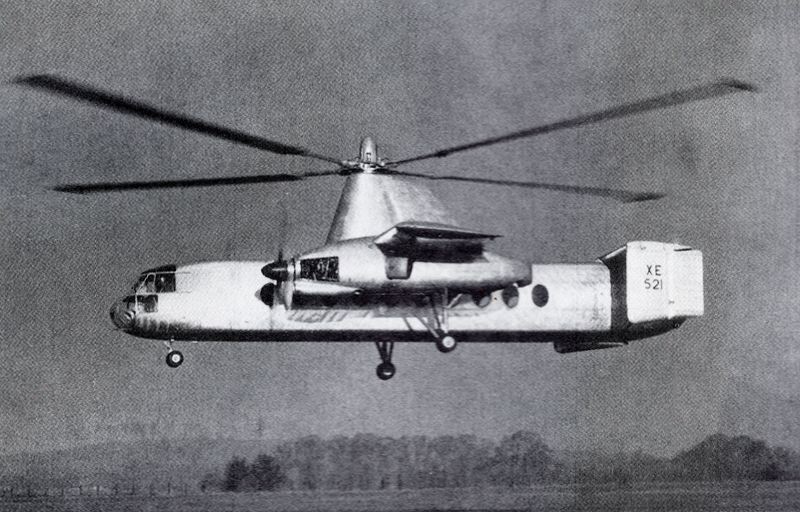

To eliminate the possibility a temporary fixed landing gear was fitted. In this condition, the Rotodyne was flown by Squadron Leader W. R. Gellatly on 6 November 1957. Nothing like it had been seen before. It had a box-like fuselage 58 ft 8 in long, with the two pilots in the extreme nose and a 46ft cabin behind.

Fairey Rotodyne Propellers

The prototype Rotodyne was fitted with a pair of Napier E and NE17 turboprops driving 13ft diameter Rotol propellers.

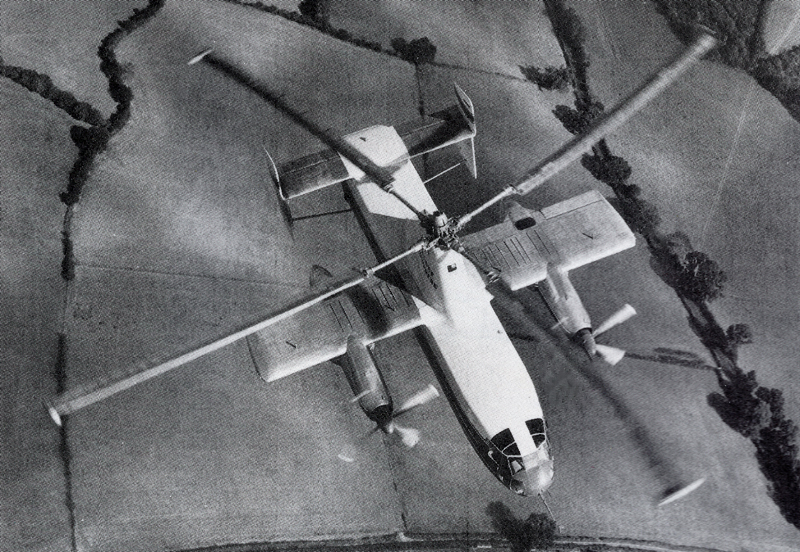

Above the fuselage was a stubby rectangular wing, carrying two engine nacelles. At the front of each nacelle was a 2,805-shp Napier Eland NE1.3 turboprop, with a permanent forward reduction gear to a four-blade Rotol propeller.

Fairey Rotodyne Wing

The stub wings provided lift in forward flight. The wing was fitted with trim tabs but no ailerons, roll control being obtained through the rotor head.

At the rear was a hydraulic clutch which, in the VTOL mode, drove a nine-stage auxiliary compressor, with an aft-facing inlet. The high-pressure air from this compressor was ducted up the rotor pylon and out along two of the blades (air from the other engine served the other two blades). At the rear was an aeroplane-type tail, with tailplane, tabbed elevators and twin fins and rudders.

An indication of how much trouble was encountered is provided by the fact that three flights were made on the first day! It had been intended during the first few weeks of flying to keep within the ground cushion, but, despite being at near maximum weight, the aircraft felt so good that on the final flight on the first day the pilots took it up to circuit height and flew quite a snappy circuit.

Fairey Rotodyne A proven vehicle

By 10 April 1958 speed had reached 155 mph and height 6,800ft, and on that day the first transitions were made to and from the autogyro/aeroplane cruising mode, with power to the rotor shut off, all engine torque going into the propellers.

Cruising speed had been expected to be about 130mph, but in no time the Rotodyne was flying at 170 mph and it was found that at its incidence setting of 4° the wing was overloaded and the rotor doing too little, resulting in blade flapping and inadequate control margins. Accordingly the wing was reset at 0° and fitted with ailerons.

OPERATORS

Launch customers for the Rotodyne were to have been Okanagan of Vancouver and Japan Air Lines, who signed letters of intent with Kaman Helicopters, who held the sales, service and manufacturing licenses in North America. New York Airways, the New York-based helicopter operator, also signed up for the Rotodyne, seduced by its high speed and ultra-low seat/mile costs. BEA was the main British customer for the aircraft.

Soon transitions were being made routinely down to blind instrument conditions at 300 ft. The landing gear was unbraced and allowed to retract, and by the end of 1958 it had been decided to set world speed record.

Though the Eland engines were somewhat down on power it was decided to set a record in the new E.2 Convertiplane category, round a 100-km closed circuit, between White Waltham and Hungerford.

Gellatly and Morton were the pilots, and on 5 January 1959 the Rotodyne set the circuit record at 190.9 mph, 49 mph faster than the existing circuit record and 30 mph above the straight-line helicopter record.

Thus, by 1959 the Rotodyne prototype was a proven vehicle which, with no more than cosmetic changes, could have gone into production for various civil and military transport purposes.

Predictably, as it was so far in advance of any other VTOL vehicle in the world, interest was worldwide. In 1958 Kaman Aircraft of Connecticut had negotiated a license for sales and service, and possible manufacture, in North America.

New York Airways, already operating helicopters on a big network around New York City at seat-mile costs of about 25c, had been searching for a bigger helicopter that could get costs down to about 12c now, with the Rotodyne, it looked as if costs could be brought down to around 4c, combined with much higher speed.

POWERPLANTS

The prototype Fairey Rotodyne was powered by a pair of Napier Eland turboprops, each rated at 3,000shp. The 70-seat production version was to have been powered by 5,250-shp Rolls-Royce Tynes, each driving a 14ft diameter de Havilland airscrew and delivering air to pressure jets at the rotor tips.

It promised better travel at subsidized fares similar to those for surface travel, all far beyond NYA’s wildest dreams. In March 1959 NYA, jointly with Kaman, signed a letter of intent for five, with a further 10 on option. The unit price was about $500,000, and delivery was due in spring 1964.

Unfortunately, as is invariably the case with any new development, by 1959 the original Rotodyne had begun to look rather small and low-powered. The original sponsor, BEA, judged that with what were initially meant to be fairly minor changes (the chief one was to switch from the Napier Eland engine to the Rolls-Royce Tyne) the Rotodyne could be upgraded to carry 70 passengers at 200 mph.

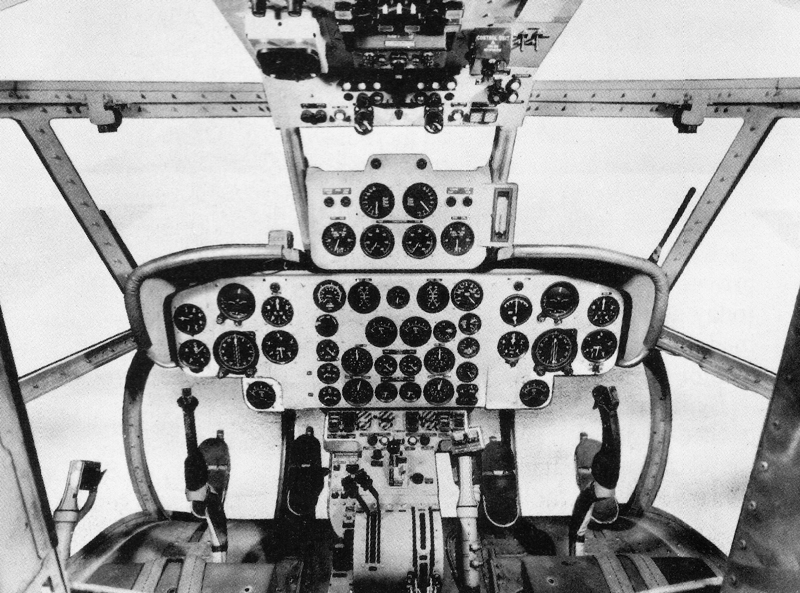

The cockpit of the Rotodyne was sparsely furnished even by the standards of the late 1950s, but the all round view was excellent. Like a helicopter, the pilots had a stick and a collective pitch lever.

This was unquestionably possible, and during the winter of 1958-59 Fairey schemed the FA.1, or Rotodyne Type Z, as the definitive production version. The Rotodyne Z had a more capacious fuselage, with the cabin length increased to 50ft.

The Tynes, each rated at 5,250 shp, drove the propellers only. At the rear was an RB.176 air compressor, this being a specially designed engine for this application. To this were added an extra independent LP turbine driving the auxiliary compressor for the Rotodyne rotor.

Fairey Rotodyne No lack of interest

Overall, weight was increased about 1,5001b, but rotor horsepower was almost doubled. Rotor diameter was increased to 104ft, and to reduce the formidable noise the pressure jets were made in two-dimensional form occupying the final 4ft of each blade.

These new pressure jets were proven in extensive ground testing. Even today no subsequent helicopter system has made it possible to put so much power into a rotor for so little weight and drag.

By the end of 1959 D. Napier & Son had ceased to develop aero engines, except for the Gazelle, which in 1960 was passed to Rolls-Royce, so the original Rotodyne power system was in any case no longer available. With the two Tynes and two RB.176 compressors the Rotodyne Z could certainly have been certificated at the new design weight of 53,5001b, at which it could have cruised at 205 mph whilst carrying 57 passengers and their baggage over a 250-mile sector with full allowances.

The prototype Rotodyne was unfurnished and full of test gear, but could have accommodated 10 rows of four seats, separated by a central isle.

Cargo payload would have been 18,500lb. A proposed military version, with almost the same airframe, would have been cleared to 60,0001b. It would have earned 70 troops or a 21,0001b payload.

At first there seemed every likelihood that the production Rotodyne would go ahead. The Government had said it would pay about half the estimated development cost of $8-$10 million, and the assurance of a development contract seemed certain after, on 8 February 1960, Fairey Aviation had merged its helicopter activities into Westland Aircraft, in accordance with the wishes of the politicians.

Westland also took over the helicopter activities of Bristol and Saunders-Roe Ltd, and thus instantly became the sole British helicopter company and the politically favored instrument.

There was certainly no lack of interest among customers all over the world, led by BEA at home and by NYA abroad. Thanks to sustained rig and tunnel testing there were almost no remaining unanswered problems, and the world seemed to be on the brink of what so many had wanted for so long: a really capable and economical VTOL airliner.

The Rotodyne originally flew with a fixed braced undercarriage and with three small fins under the tailplane. The noise was described as being like a heavy locomotive pulling a heavy train uphill.

Fairey Rotodyne Indecision

Unfortunately, what happened next was. that in true British fashion, those responsible for taking decisions simply dithered. Westland seemed to have so much on its plate it had little time to spare for its biggest and potentially most important product, and when it was approached by the many potential Rotodyne customers and licensees the Yeovil company exuded indecision and uncertainty. The result was predictable. In April 1960 Okanagan cancelled its order because the delivery schedule could not be met.

The 10-year saga of the Rotodyne, which had brought Britain to the point where all it had to do was go into production with a world-beater, was finally ended by cancellation of the program on 26 February 1962. Nothing much had been done in the previous two years. BEA had chickened out, and so had the Army, the RAF and Westland. The only people who had not were the foreign customers.

The Rotodyne soon gained larger tailfms, which extended above the tailplane and were initially canted outwards.

Be the first to comment on "Fairey Rotodyne Rotorcraft"