Helicopter Private Pilot License

How easy is it to become a helicopter pilot?

What do you need to know to be able to fly a rotorwing?

What can you do when you’ve gained your licence?

Derek Haynes reveals all… courtesy – UK Flyer February 1995

It’s probably true to say that of all available forms of flying machine, the helicopter is the most flexible. They can be fast, they can be slow; they can be used for serious place-to-place travel, or they can be used for detailed observation and surveying trips; they are welcome at big airports, and yet can land in tight spaces – at venues which often have a very high profile, such as horse racing, the Grand Prix and other large events.

The R22 is the basic helicopter training model.

Most helicopter designs have an all-round visibility which is vastly greater than that in most aeroplanes, and that gives you an unbeatable view of the countryside as you fly over it.

So why isn’t everybody up there chuntering around in helicopters? There are several reasons, but the two main ones are probably cost and confidence in obtaining your helicopter PPL. “A triumph of technology over aerodynamics is how you often hear helicopters described; a collection of spare parts in close proximity” is another popular description.

Many fixed wing pilots wouldn’t (or claim that they wouldn’t) be caught dead in a helicopter because “they don’t look safe”. Mind you, they usually change their tune when they are actually offered a flight…

How it works

Despite these reservations, and an occasionally bad press based upon such prejudice, helicopter flying is on the up with an increase in helicopter PPL completions. So what do you have to become a helicopter pilot and join this elite band of sky bandits?

To obtain your PPL(H), you must have flown at least 40 hours, of which 10 hours must have been solo. You will also have to have passed several ground papers, similar to those for the fixed wing PPL (so they cover aviation law, navigation, meteorology and human performance as well as the helicopter technical exam).

You will also have to pass a class 3 medical for your helicopter PPL – nothing to worry about if you are fit and healthy. The biggest part of the license requirements, though, are the flying hours.

In those 40 or so hours you will learn how to control the aircraft in the air; how to taxi; how to take-off, fly a circuit, hover and land; how to glide the helicopter (called autorotating’) so that, among other things, you will be prepared for an engine failure; navigating while flying the helicopter.

Finally for your helicopter PPL, you’ll learn advanced techniques including landing in a confined area, landing and lifting off from sloping ground, steep turns, quick stops and all manner of other things — including, probably, pirouettes and other balletic manoeuvres close to the ground which will teach you to keep better control of your helicopter close to the ground.

The culmination of the training is the flight test, which will make sure that you can control the aircraft and will be safe to fly as pilot and command and carry passengers.

The helicopter PPL: Manoeuvres

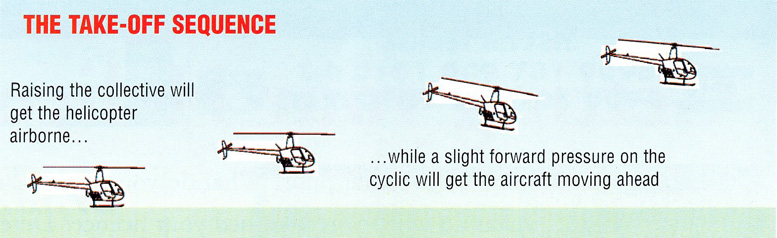

As with all flying, the crucial phases of flight are those that are in proximity to the ground: taking off, taxiing and landing. Taking off requires the pilot to set the correct hover rpm using the throttle, adding a touch of pedal in anticipation of the torque that you will get when the aircraft leaves the ground, and raising the collective lever.

As you become airborne, small adjustments to the throttle, pedals and cyclic stick will be required to keep the aircraft balanced and straight.

Hovering at a height of about three feet (hovering is probably the most important helicopter skill to learn, and the most difficult) a turn controlled with the pedals will check that the hovering area is clear and that your climb-out area is safe.

Pushing the cyclic gently forwards will start the helicopter moving forward; as the airspeed builds, raising the collective will get you climbing — this gives you the familiar nose down attitude of the helicopter as it is taking off.

Eventually you will have gained enough speed to be able to bring the nose back up, so that the aircraft is now flying in a level attitude although it will still be climbing due to the raised collective lever.

helicopter PPL: Landing the helicopter

The most crucial phase of the average flight is the landing. Helicopters often fly a circuit similar to a fixed wing aircraft as their approach; whether they fly a circuit or not, they will usually land into the wind.

If you are flying a circuit pattern, the descent will begin at a point abeam the landing site, which is also the point at which you will begin the turn that will eventually lead you to the final approach run; you will also begin to let the airspeed bleed off.

You will have to add some power to make up for the lack of forward movement which had been helping to keep up the airflow over the blades and so generate lift. By the time you are on the final approach you should have picked out a spot on the landing site as an aiming point’.

The Jet Ranger is one of the most popular aircraft in this country – a regular visitor to big sporting events.

Keep this fixed in the same position on the helicopters windscreen as you begin your descent, and keep it fixed during the approach.

This will give a steady approach angle. As you get near the landing zone the airspeed should be dropping gradually so that you eventually arrive over the touchdown spot at a hover, from which you can gently place the helicopter onto the ground by lowering the collective.

THE MAIN CONTROLS OF A HELICOPTER

There are four main controls in a basic training helicopter PPL: the cyclic, the collective, the pedals and the throttle. The cyclic , or control column, is the helicopter’s joystick. It controls the pitch and roll of the helicopter, rather like the control column affects the movements of an aeroplane.

The collective controls the climb and descent of the helicopter, by altering the pitch of the rotor blades and therefore the amount of lift that they generate. Why the ‘collective’? Because by a clever series of gearings it alters the pitch of all the blades at once.

One of the piloting skills needed is the smooth co-ordination of the cyclic and collective in order to achieve the various manoeuvres required. The final piece of the co-ordination jigsaw is the pedals.

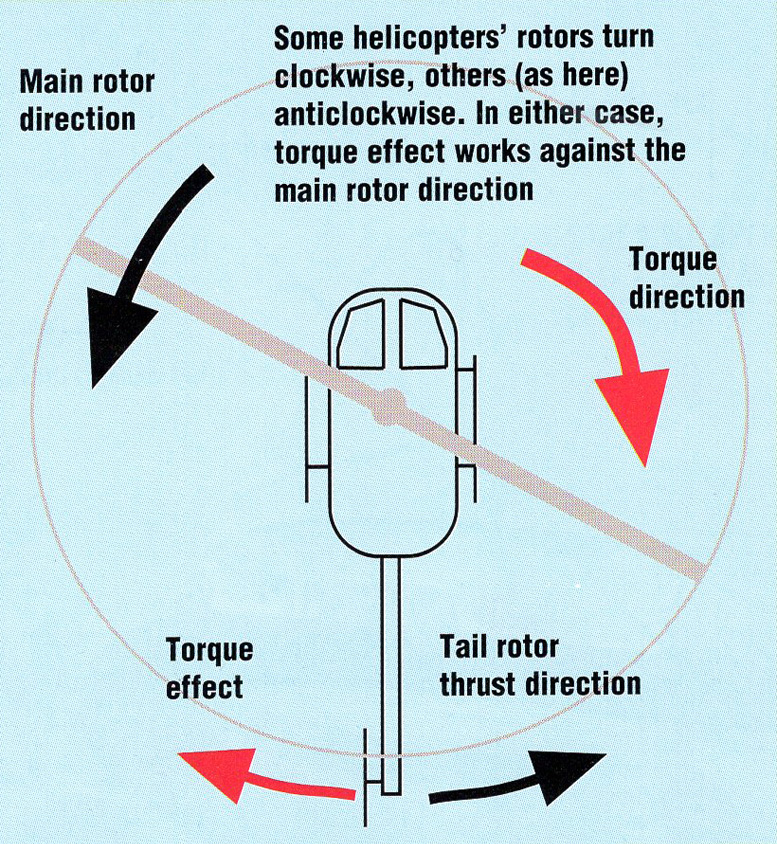

These alter the pitch of the blades in the tail rotor, and therefore the extent to which the helicopter’s inherent torque effect affects the aircraft. In other words, they affect the aircraft’s spin.

When they are in a neutral position the helicopter will point forwards, but if the pilot applies a touch of left rudder the nose will swing to the left; if he applies the right rudder, the nose swings to the right.

The final control is the throttle which, not surprisingly, controls the amount of power that the engine produces. In the cockpit is actually fitted to the collective lever, so that it appears rather like the grip on a car handbrake and works rather like the throttle on a motorbike.

Other helicopter controls

There are, of course, a number of other controls and switches in the cockpit – carburetor heat being one of the more important – along with (probably) radios and a number of dials that communicate various pieces of status information to the pilot, but the majority of the pilot’s time is spent concentrating on these four main ones.

Indeed, unlike a fixed wing aircraft, the pilot of a helicopter must keep a constant hand on the controls. A recent helicopter crash revolved around the pilot removing his hand from the collective in the landing phase of flight. He lost control and the aircraft was destroyed, although the pilot happily escaped without injury – that minor lapse could have been fatal!

helicopter PPL: In the cruise

The majority of your flying time, though, comes between the take-off and landing in the cruise. This quickly becomes quite natural. The main tool is the cyclic, which allows you to bank and alter the pitch of the aircraft rather like the control column on a fixed wing aeroplane.

Once you’ve mastered all the basic aspects of handling a helicopter, you will be ready to move on to some of the more advanced manoeuvres.

Steep banking turns in the cruise, and you’ll be introduced to various types of landings and take-offs which will open up the number of landing sites that are available to you considerably: confined spaces, sloping ground, coping with reduced power (and with no power at all) – an extension of the autorotational exercises that you will have practiced.

You will also be taught in your helicopter PPL how to deal with the various emergencies that can arise: power loss and forced landings, vortex ring (sometimes described as the helicopter version of stalling), quick stops (moving from high speed cruise to the hover quickly and safely) at low level, and so on.

HOW THE HELICOPTER WORKS

One of the most important things to understand as a pilot is how a helicopter gets airborne, and then stays there. The answer lies in the rotors, which are, in effect, the helicopter’s wings. Like a fixed wing aircraft, a helicopter needs lift and it is the rotation of the blades that provides this.

Attacking the air at an angle, they produce the same Bernoulli affect as you’d expect over a wing, generating the necessary lift. The angle of the blades, and therefore the amount of lift that they generate, can be altered by the pilot.

Of course the blades can only produce lift when there is airflow over them (which is why an aircraft doesn’t take off until it has sufficient speed), so the helicopter needs an engine to turn the blades to create that airflow.

But what if the engine stops?

It’s no disaster: assuming that the helicopter is airborne, the various lift forces and airflows act on the blades to keep them turning, so that they still generate lift. Not as much lift as when the engine is turning them, it’s true, but enough to stop the aircraft falling out of the sky and, in addition, to give he pilot some control.

Talking of torque

The idea of having spinning blades on top of the aircraft is all very well, but it creates another problem. The blades’ twisting in one direction has a reaction, which is that the helicopter itself wants to twist in the other direction.

Engineers have come up with a number of ways of counteracting this effect, but the only one that is in general use in helicopters is the tail rotor: this acts rather like a propeller. forcing the tail of the helicopter round in the opposite direction to the twist (or ‘torque’) generated by the main rotor.

One skill of helicopter piloting lies in balancing the main and tail rotor effects using the pedals. These alter the pitch of the tail rotor blades, and so vary the amount of ‘anti-torque’ effect on the aircraft, which means that the pilot can slowly spin the helicopter round on the spot.

The torque effect of the rotors is offset by the tail rotor.

Finding your way round

While you’re doing these advanced exercises, your instructor will also begin to introduce a navigational element into your lessons. You’ll be expected not just to be able to fly the helicopter, but also to know where you are as you are doing it.

As your confidence increases, you will find that it all becomes much easier, until eventually you are ready to take – and pass – the helicopter PPL flight test, and you are a fully-fledged helicopter pilot.

Summer is the ideal time of the year for the helicopter; starting your helicopter PPL course now could mean that you are ready to fly your first passengers to a local hotel for lunch when the sun is out and the breeze is gentle.

Yes, it can be more expensive than fixed wing flying, but there are plenty of helicopter schools around the country: check out the ads in this issue for your closest one and get out there and make those rotors whirl!

You won’t regret it!

ONCE YOU HAVE YOUR HELICOPTER LICENSE

Helicopters can get you to some stunning places…

There are several other ratings that you can move on to tackle once you have passed your helicopter PPL(H). You can get a night rating, for instance, although there is no such thing as an IMC(H) rating in this country, as helicopters must remain in sight of the ground at all times.

However, there are other challenges: conversion courses to turbine engined aircraft and a twin rating are both available. Beyond that there are the professional licenses, or there is instructing. But even if extra ratings aren’t what you want, there are a whole host of places that you can use your helicopter license to visit.

There are a number of guides that will help you make the most of your new freedom: and the FLYER Guide to helicopter landing sites will be available shortly: if you start learning now it will be waiting for you when you’re ready to use it!

Be the first to comment on "Getting your Helicopter PPL"