High Performance Hingeless Rotorhead BK Helicopter

With its new single-pilot IFR certification and quiet, elegant interior, the MBB BK 117 is dressed for success. Executives take note.

ARTICLE DATE: March 1990

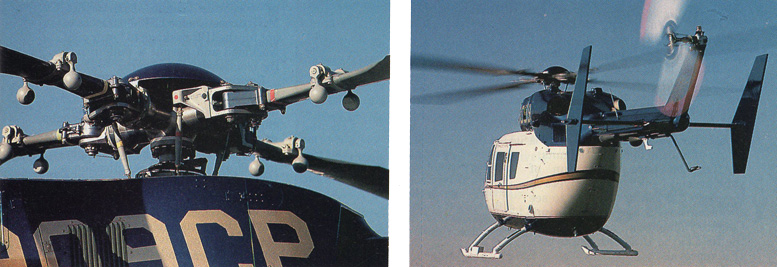

THE MBB BK 117 HELICOPTER’S unique hingeless rotor system makes it the quickest and most maneuverable civilian helicopter in the world. And with enough power reserve to fly out of almost any situation after an engine failure, it has become a global star in all manner of utility and emergency medical service (EMS) missions.

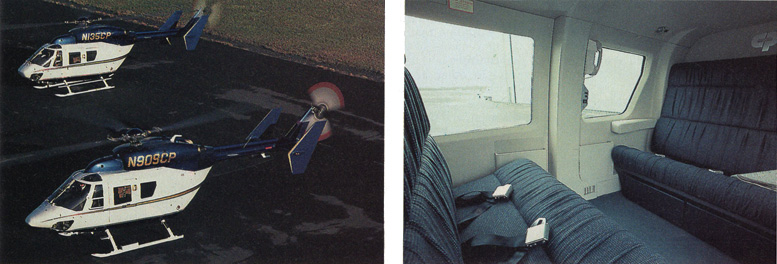

When nothing but water and cityscape surround the helipad, the BK 117’s twin LTS 101s and fine engine-out performance are a comfort.

Until now, however, the executive version of the rugged helicopter had all the tailored grace of Dick Butkus in a Brooks Brothers suit, the epitome of flying muscle attempting executive elegance. Needless to say, it failed to take the corporate mission by storm.

That has all changed with certification of Honeywell’s single-pilot IFR automatic flight-control system and the development of Custom Aircraft Completion’s “cocoon” interior. With the new avionics, the BK 117 can fly IFR when necessary, and in all conditions the electronic pilot can outperform the human pilot when it comes to giving a smooth ride.

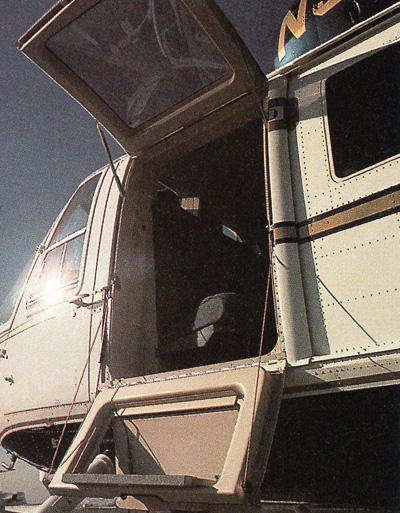

Meanwhile, the BK 117 cocoon interior is another boon to passenger comfort. By using rigid panels attached to the airframe by vibration isolators, Custom Aircraft has further reduced sound levels in an already quiet cabin.

The BK 117 is a growth version of the BO 105, one of the first light twin helicopters. Both are built by Messerschmitt-Bolkow-Blohm (MBB) in Germany. Ludwig Bolkow developed the hingeless—often incorrectly called “rigid” — rotor system in the 1960s.

In 1967 the BO 105 first flew using Bolkow’s rotor, and in 1971 it was certified in the U.S. Helicopter rotor blades are subject to continuously varying loads in flight, because the speed of each blade at any moment is the sum of its rotational speed around the mast and the forward speed of the helicopter.

An “advancing” blade—one whose leading edge points the way the helicopter is going—is consequently flying at a much higher airspeed than a “retreating” blade.

To deal with constantly varying lift and drag, conventional rotors use hinges and dampers to allow individual blades to flap up and down, swing forward and aft, and change their angle of attack.

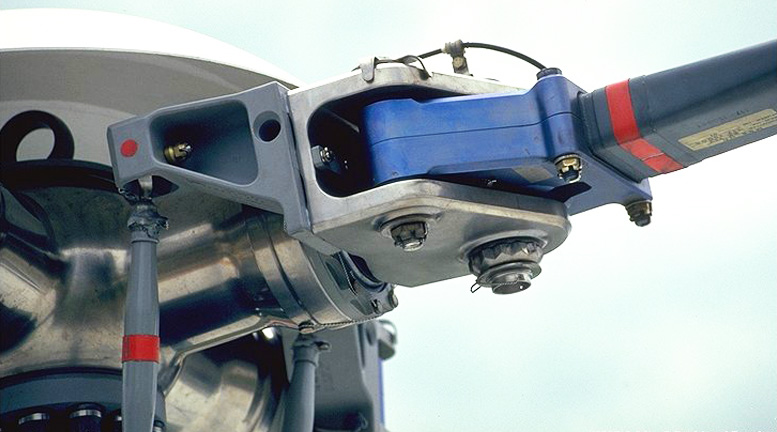

Bolkow’s goal was to create a simpler and more rugged rotor by eliminating all of those hinges and dampers. The solution was a main rotor head and blades strong and yet flexible enough to absorb flapping and lead-lag loads without hinges.

The MBB main rotor hub is a single massive forged piece made of titanium to provide the necessary strength, and the rotor blades are a fiber-reinforced composite to provide strength and flexibility. The blades are flexible enough to handle the flapping and lead-lag loads, yet so durable that they have no fixed-life limit.

Without hinges, the rotor head is bolted directly to the helicopter airframe, unlike other systems that suspend the machine below the rotor pendulum style. For these reasons the Bolkow hingeless rotor is the most responsive rotor system thus far and has proven incredibly durable in the worldwide fleet of BO 105s and BK 117s.

And no component of the rotating system has an overhaul or life limit shorter than 1,200 hours. When the larger BK 117 was developed in the late 1970s, the basic hingeless rotor system of the BO 105 had plenty of growth potential to carry the extra weight.

The airstair door eases entry and egress, and the main rotor stays far above passengers’ heads for safe loading.

All BK 117 mechanical components are above the cabin, creating 200 cubic feet of unobstructed space. The BK 117, which entered service in the U.S. in 1983, is a joint venture between MBB and Kawasaki Heavy Industries of Japan.

Aside from the main and tail rotor systems, MBB is responsible for the BK 117’s controls, system integration, tail and skids. Kawasaki builds the fuselage and transmission, the latter having been developed by Kawasaki from an earlier design. Both companies have final assembly lines.

All helicopters sold in the western hemisphere are built by MBB in Germany, and Kawasaki assembles the BK 117s sold in the Far East. MBB chief pilot A1 Myers is a former Edwards AFB test pilot and is in love with the helicopter.

In fact, the flying qualities of the BK 117 are so spectacular that the U.S. Navy sends pilots from its Patuxent River test-pilot school to MBB just to experience them. As an exercise, Myers and I flew through many of the maneuvers that the Navy pilots use to measure performance and response.

The BK 117 I was flying was destined for offshore oil-rig support. The big instrument panel had only the basics—one com, a loran and a transponder, but no VOR nav. The cockpit is roomy with excellent visibility, thanks to big windows in the door and overhead.

The Lycoming LTS 101 engines powering the BK 117 have been troublesome in other applications, primarily the U.S. Coast Guard’s Dolphins and the Bell 222. Engine life has been shortened by several AD notes, but actual engine problems are uncommon in the BK.

Takeoff power is limited to 550 SHP in the BK compared to 684 in the Bell 222, because the BK weighs about 1,200 pounds less. The lower power demand can easily explain the good success BK 117 operators have had with the engine. Improved components from Lycoming are at last relieving problems addressed in the AD notes.

The new BK 117 is sleeker outside with its streamlined radome nose, and more comfortable inside thanks to the solid, quiet “cocoon”.

The BK 117 uses redundant hydraulic systems to boost the flight controls, and the redundancy and isolation between the two systems is so great that the combined system is certified as fail-safe, meaning that if the rotor is turning, you will have hydraulic boost for the controls.

The hydraulic boost is powerful, but the cyclic has a good, firm feel, a far cry from many helicopters whose handling can be best compared to that of a 1955 Chrysler with power steering, a machine devoid of any road sensation. A stick position augmentation system automatically adjusts the BK’s control response, so pitch feel remains constant over the operating speed range.

Because the BK 117 hingeless rotor system is so responsive and the control system free from slop, only tiny control movements are needed to fly the BK 117. The preliminary tendency to overcontrol is quickly tamed by the realization that mere pressure—not movement—of the cyclic is enough to control a hover.

In other helicopters, particularly the teetering-rotor types, you need to make a bigger initial control movement, and then quickly move the controls back toward center to make up for lag in the system.

The hingeless rotor system responds to pilot inputs in about one-tenth of a second compared with half a second for a conventional articulated rotor, and nine-tenths of a second for the two-blade teetering-rotor systems. On a cool day, with full fuel and only Myers and me aboard, the BK 117 climbed out at more than 2,000 fpm pulling only maximum cruise power.

Even fully loaded, the helicopter can climb at 1,900 fpm using take-off power. Typical indicated cruise airspeed is around 135 knots, and the low vibration level doesn’t increase noticeably as you near redline.

The big panel has plenty of room for state-of-the-art IFR avionics.

The responsiveness of the machine is so great that I couldn’t resist the temptation to bank 45 degrees for a normal turn. Turns only began to feel steep at 75 degrees of bank and, with a little more power and back pressure on the cyclic, I could easily hold altitude with the bank angle around 80 degrees.

The BK 117 can be pushed over to a -1 G while other types of rotor systems can be dicey at anything less than a positive G. A flick of the wrist sends the helicopter into an impossibly tight turn at low airspeed, all without worry of exceeding any kind of rotor limits.

It’s nice to know that you can push over hard in the BK 117 — and we all love to try it — but I couldn’t think of a situation where that would be useful. Myers has. He had me zero the airspeed in a hover at 3,500 feet, and he suddenly pulled back both engines.

A quick forward jab of the stick dumped the nose 15 degrees, and in less than three seconds and 150 vertical feet, I had 50 knots of airspeed. When you need airspeed in a hurry, pushing over is the fastest way to get it, but that’s generally risky business in other helicopters.

The BK 117 matches the single-engine performance of any of the popular twins and betters most. If a little higher airspeed is maintained during approach, the helicopter is almost always in a position to go around if one engine fails. Of course, weight, wind and air temperature extremes can make a single-engine go-around impossible in any helicopter.

I made an engine-out approach to a running landing, which is normal procedure, but it wasn’t necessary because at our weight the BK 117 would easily hover on one engine. The mast moment indicator, a gauge showing the loads the rotor is placing on the rotor mast, is another unusual feature of MBB helicopters.

If limit loads are exceeded, a light comes on and an inspection is required. Mast moment loads are only a big factor when landing on a slope, because the helicopter is tilting, but the rotor disc is trying to fly level.

The BK 117 is approved for slopes of 11 degrees down to the left and eight degrees in all other directions. I landed it on the side of a hill and never saw the mast moment indicator approach the yellow arc, so there is plenty of margin in the slope limits.

After the pure flying fun of yanking and banking with Myers in the basic BK 117, it was time to see the ultimate corporate version, Colgate-Palmolive’s new machine, the first in the U.S. with single-pilot IFR approval.

The aircraft features Honeywell’s SPZ-7100 automatic flight-control system, which is dual-redundant and can be used as a stability augmentation system (SAS), an attitude-hold system or a fully coupled autopilot with the complete range of modes.

The panel is completed with dual Honeywell Primus II radio systems, a UNS-1 navigation management system and dual Bendix/King electronic HSI 40s. There’s an airstair door on the left, and the cocoon interior surrounds up to six passengers with solid comfort.

The winter wind was howling out of the northwest after a cold frontal passage, and everybody flying over northern New Jersey was complaining about more than moderate turbulence below 8,000 feet. It was a great day to test an autopilot.

During hands-on flying I found that the SAS adds stability by damping out short-term attitude excursions. The yaw damper is left on at all times and really takes the squirm out of bumps. With the attitude-hold mode engaged, the helicopter managed to stay in the proper attitude despite the turbulence.

You can press a button on the BK 117 cyclic to readjust attitude by moving the cyclic, or you can simply use the trim switch to fly to a new pitch or roll attitude. When flying IFR, or otherwise on an assigned altitude and course, the autopilot coupled modes are the only way to go.

Set the assigned altitude in the alerter and the Honeywell system captures and holds it. Move the heading bug, and the BK 117 smoothly rolls into a 20-degree bank turn with a passenger-pleasing gentle touch.

The hingeless main rotor head is strong.

With the UNS-1 navigation management system showing a direct cross-wind of 29 knots, the SPZ-7100 captured the Runway 6 ILS at Teterboro and maintained centerline until leveling automatically at 50 feet AGL. Human pilots need only manage airspeed by moving the collective.

It was an amazing piece of precision flying under extreme conditions. From just after liftoff until short approach, the SPZ-7100 was flawless, and its deft touch on the controls delivered a better-quality ride than any human pilot could under the conditions.

The BK 117 will continue to lead in the EMS field because of its huge cabin and excellent access through the rear clamshell doors, but the IFR system will make it more attractive to corporate flight departments.

MBB expects some EMS operators to opt for the IFR package to lower pilot workload and permit a pull-up into the clouds when necessary. Earning the single-pilot IFR approval required some electrical-system improvements to ensure uninterrupted power for the autopilot system, and that has made all BK 117s better.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the IFR certification is that people who never before considered the BK 117 will now sit up and take a look. Pilots will fall in love with the machine, passengers will appreciate the room, low vibration and speed, and bean counters will find little to criticize in the price.

The BK 117 flown and photographed for this report was equipped with a Honeywell SPZ-7100 single-pilot-qualified three-axis automatic flight-control system.

Flight data was displayed on dual crosspointer mechanical Honeywell flight directors and on dual Bendix/King EFIS 40 electronic HSIs. A Bendix/King RDS-82 digital color weather radar also displayed information on the HSIs.

Dual Honeywell Primus 11 radio packages provided navcom, ADF and transponder functions. A UNS-1 multisensor navigation management system was coupled to a Loran sensor to handle all nav duties.

Airframe options included a Freon air-conditioning system and bleed-air heater in place of the standard air-cycle environmental system. The six-passenger cocoon interior with airstair door was installed by Custom Aircraft Completions.

All airframe and avionics options increased empty weight to 4,730 pounds, leaving a useful load of 2,335 pounds. The base price listed is for the single-pilot IFR package and cocoon interior.

| MBB BK 117 Helicopter Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Base price | $2.85 million |

| Engines | Lyc LTS 101-750.592 shp each |

| TBO | 2,400 hrs |

| Main rotor diameter | 36.1 ft |

| Maximum seats | 11 |

| Length | 42.7 ft |

| Height | 12.6 ft |

| Maximum takeoff weight | 7,055 lbs |

| Standard empty weight | 3,807 lbs |

| Maximum useful load | 3,248 lbs |

| Maximum sling load | 2,205 lbs |

| Main rotor disc area | 1,023 sq f |

| Main rotor disc loading | 6.9 lbs/sq ft |

| Power loading | 6.4 lbs/shp |

| Maximum standard fuel | 1,230 lbs |

| Maximum rate of climb | 1,910 fpm |

| Ceiling (certified) | 15,000 ft |

| SE service ceiling | 5,800 ft |

| Hover in ground effect | 9,600 f |

| Hover out of ground effect | 7,500 ft |

| Cruise speed | 135 knots |

| Fuel flow in cruise | 400 pph |

| Maximum endurance, standard fuel | 3.1 hrs |

Be the first to comment on "Rigid Rotorhead MBB BK 117 Helicopter"