Helicopters Fighting Fire From The Sky

ARTICLE DATE: October 1977

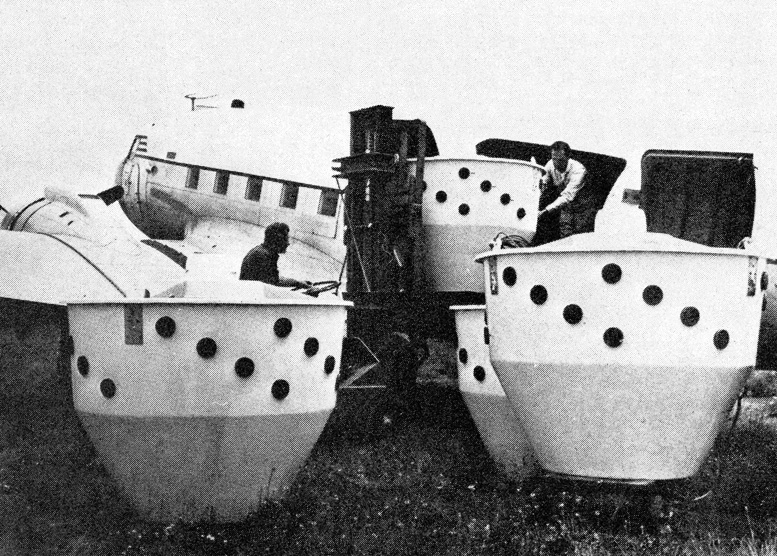

The helicopter and the fiberglass bucket make a highly efficient firefighting team.

“Thank God, here come the flying firetrucks,” he shouted to his buddies, His tired eyes had picked up a loosely strung out flight of helicopters beating toward the large fire. Each ship was towing a large bucket at the end of a line. Indeed, it was an airborne bucket brigade.

This ancient concept of firefighting, complete with steam pumpers, spotted dogs and galloping horses, is making a valuable comeback with the help of modern technology, helicopters, and the U.S. Forest Service.

These modern buckets are made of fiberglass, built to hold up to 450 gallons, and have proved to be effective in knocking down various types of fires by aerial bombardment. The buckets are hauled to the fires by helicopters, slung under the ship at the end of a cable and tow line.

They can be emptied in a variety of patterns and intensities using a remote control electrical system operated inside the ship. According to Robert Lake of the Forest Service, helicopters carrying fire retardants are now used in fighting virtually all fires on National Forest Land.

A quick sampling of states with large outdoor fire problems showed that all make great use of the helicopter/bucket brigade idea in fire control, especially of large wooded or field areas.

A fleet of the flying firetrucks can carry out a systematic aerial dousing of a forest fire by lining up in an attack string of ships, then flying over the fire and dumping the loads from the fiber-glass buckets.

After the dump, the ships haul the empty buckets back to the refill point for more water. The cycle is repeated until the fire is under control. Foresters and firefighters have always looked at various aircraft to drop water and chemicals on forest fires.

The initial effort was made in this country in 1921, using a converted DH-4, a World War I vintage bomber. There were other scattered attempts at aerial firefighting through the twenties, and by 1936 the U.S. Forest Service began to use aircraft extensively.

Naturally, World War II curtailed this effort, and it was not until 1950 that the Forest Service got back into full aviation operation, with the help of the Air Force. Tactical air support was a major part of the firefighting operations, using converted military aircraft and light civilian ships.

The concept of fixed wing aerial bombing is not nearly as efficient or effective as the flying firetruck method. The helicopters overcome the disadvantages of inaccuracy, poor water spread, danger to ground personnel, and limited operational capabilities, e.g., low altitude operation, flying in canyons and deep wooded areas, etc.

The summer of 1967 brought horrible forest fires to the Pacific Northwest. Roaring through valuable timber and park areas, the killer fires were burning away from the men gamely trying to combat them with all of the traditional methods.

Forest Service officials huddled literally in the smokey forest and decided to try the small group of experimental helicopters with their new water dumping concept—the flying firetrucks with the prototype fiberglass buckets. The small fleet of ships dropped more than 450,000 gallons of water and chemical retardants. The idea worked!

According to Monte Pierce, then national air officer of the Forest Service, the helicopter firefighters ships and buckets were highly effective. Their crews served with bravery and distinction.

“Their versatility, mobility, and payload have mad e these flying firetrucks highly effective in controlling serious forest fires. They’re a great help to timber conservation.” Mr. Pierce noted.

The attack concept of the flying firetrucks is, of course, controlled by the type, size, and location of the fire. In the forest fires that typically hit Northern California, Oregon, and Washington each summer, the flying firetrucks use both a squad flying formation and a circular pattern somewhat like a bucket brigade.

Altitude for the actual drop is decided upon by the pilot after considering safety and operational factors, e.g., wind, density altitude, terrain, type of fire, etc. In any case, the minimum drop altitude is 75 feet for light ships and 150 feet for the larger helicopters.

In addition to safety factors, operating at lower altitudes will only add to the fire, as the rotor downwash will fan the blaze. The water or water and retardant is dropped from the bucket through its “door” operated by the pilot or observer inside the ship.

The helicopter firefighters bucket’s “door” can be opened by degrees, allowing a variety of density and patterns in the water drop. The Forest Service also lent their firetrucks to the war effort.

In 1968, six of the large buckets were shipped to Vietnam for field tests in fighting combat-related fires. Forest Service personnel went along to show their military counterparts how to utilize the bucket brigade concept.

“The ships go in and handle the worst of it. It keeps my men out of the danger areas until it’s time to go in and mop up the little pockets of fire that somehow survive the stuff from the choppers,” an engineer sergeant remarked, visibly impressed with the flying firetrucks.

When Viet Cong rockets started serious fires in the Saigon-Cholon are a during the Tet Offensive, a single CH-47 A helicopter, hauling two 450 gallon buckets in tandem fashion, applied water to the fires at the rate of 5400 gallons per hour, enough to knock down fire at the rate of an acre per helicopter hour.

A three ship helicopter firefighters squadron put out the worst of Cholon’s man y fires in just under two hours—working under combat conditions.

Under domestic conditions, where the only enemy is the forest fire below, performances are even more impressive. All it has taken is the application of technology to an old idea, and keep adding new wrinkles.

The modern bucket brigade uses two sizes of buckets—one with a maximum capacity of 140 gallons, and a bigger brother holding up to 450 gallons. The total weight of one of the big buckets fully loaded is just over two tons.

This larger helicopter firefighters bucket is carried mainly by the Bell 204B and its military version, the UH1B. In addition, the Sikorsky S-58 also handles the larger load. Two ships, the CH-47 A and Sikorsky’s S-61, carry two of the 450 gallon tanks, providing a four ton payload.

The major requirement of these aerial firefighters is a place to drink during working hours. Either a tow-fill or hover-fill water source will do, and the closer the source is to the fire, the more efficient the flying firetrucks will be.

In Saigon, for example, the flying time to the river was only 90 seconds, so that dump and refill operations were quick, making the choppers highly capable firefighters. Of course, the choppers aren’t fussy, as any pond, lake, river, or even an artificial tank will do, just so the ship can dip or tow the bucket in the water and fill’er up.

Forest Service personnel load 450 gallon retardant containers for shipment to Vietnam in June of 1968. The fiberglass buckets and their aerial fire-trucks saved Saigon from terrible fires during the Tet offensive. (U.S. Department of Agriculture).

The refill concept is simple. It is performed either by hoverfill or towfill, depending upon the water source used. When searching for a water source, pilots are told to avoid water moving at more than 10 knots, because the combination of the moving water and the filling bucket act as a mighty sea anchor which may pull the helicopter into the water!

When the helicopter firefighters ships have a safe water source, they go down, lower the buckets into the water and let them fill. The cargo sling is activated, the filled bucket is hauled out of the water, and the ship is off to the fire again.

Chemicals may be added automatically to the water by a small accessory pump. The concept has aerodynamic benefits too. The molded, conical shaped buckets are highly stable in flight and do not add a great deal of drag for the chopper to overcome.

All helicopter firefighters controls are inside the ship, and the water may be dumped in a range of patterns and amounts. And, because of a myriad of operational options, this system can be used with a wide variety of existing helicopters.

In addition to this extreme versatility, the fiberglass bucket idea allows the helicopter to be a more efficient fire-fighter. Because of the helicopter’s slow flight capability, the pilot has better visibility and is thus able to make a more accurate drop of the water load.

These flight characteristics also allow closer air-ground coordination and communication. And when the fire is out, the helicopters may be immediately converted to other uses merely by releasing the bucket sling from the ship’s cargo hook.

Only top-rated, experienced chopper pilots fly these missions. These pilots have to cope with unexpected air turbulence, updrafts caused by the heat of fires, sudden shifting in weights due to water release, and the problems of refill flying.

Minimum experience levels for these pilots include at least 1000 hours of total flying time as a command pilot; at least 500 hours of command time flying helicopters; 200 hours of pilot time over the appropriate type of terrain he is likely to encounter on real firefighting missions; 200 hours of extended cross country flight; and an instrument flight rating.

In addition, he must hold a first class medical certificate. Not content to rest with a good thing. Herbert Shields, a Forest Service research project director, is field testing a Night Helicopter Operations project.

LEFT: Scooping a refill from a nearby river, a helicopter leased by the Forest Service prepares to join the aerial bucket brigade during a recent problem fire. (U.S. Forest Service).

RIGHT: On the scene in a Oregon fire, a Forest Service chopper refills from a portable tank amid smoke, steam and the hustle of action. (U.S. Forest Service photo).

“We’re involved with inter-agency research and equipment development to I make it possible for fire bosses to use helicopter firefighters at night or any other time when visibility is obscured.”

The project is using highly specialized infrared visual and scanner devices that bring a daylight picture of what’s happening below in the smoke, haze or night. Ralph Klondyke, conservationist and booster of the flying firetruck idea, reports that the concept is under study by business.

“Greatest firefighting idea I ever saw,” says Mr. Klondyke. “This idea is adaptable to industrial, agricultural, land management, and construction needs . . . anywhere fire suppression is required.” However, costs are a consideration, especially in the private sector of the economy.

While expensive in absolute dollars, in terms of man hours and natural resources saved, the flying firetrucks may be the world’s cheapest firefighting investment. A forest fire is a depletion of natural resources, and these losses can be translated into dollars.

The flying firetrucks used by the Forest Service, are leased only when needed. This is the most economical method. They rent or lease on an hourly basis, using their firefighting equipment on the privately owned choppers.

Operating costs for smaller ships average out to about S300 an hour, while the larger choppers cost about $900 an hour. These figures include the cost of the ship, pilot, insurance, gasoline, oil, and depreciation.

Thus, in ten years time, the flying firetrucks and their bucket brigades have passed all the tests, from forest fires to fiery operations on the battlegrounds of war. They’ve won praise everywhere for being versatile, effective helicopter firefighters. They’ve won the gratitude of the firefighters on the ground too—a most important endorsement.

A leased Forest Service helicopter heads toward a fire in Oregon’s Willamette National Forest, towing a 450 gallon fiberglass bucket full of water and chemical retardant. (U.S. Department of Agriculture).

Be the first to comment on "The Flying Bucket Brigade – Helicopter Firefighters"