Why We Love Rotary Wing Aircraft

MEASURING THE PROGRESS OF THE HELICOPTER AT THE INDUSTRY’S BIG MEET IN LAS VEGAS.

ARTICLE DATE: May 1973

Tracing the fortunes of the helicopter is a bit like running after a berserk butterfly. Potentially the universal flying machine, the helicopter is a challenge and an enigma — and an exciting adventure.

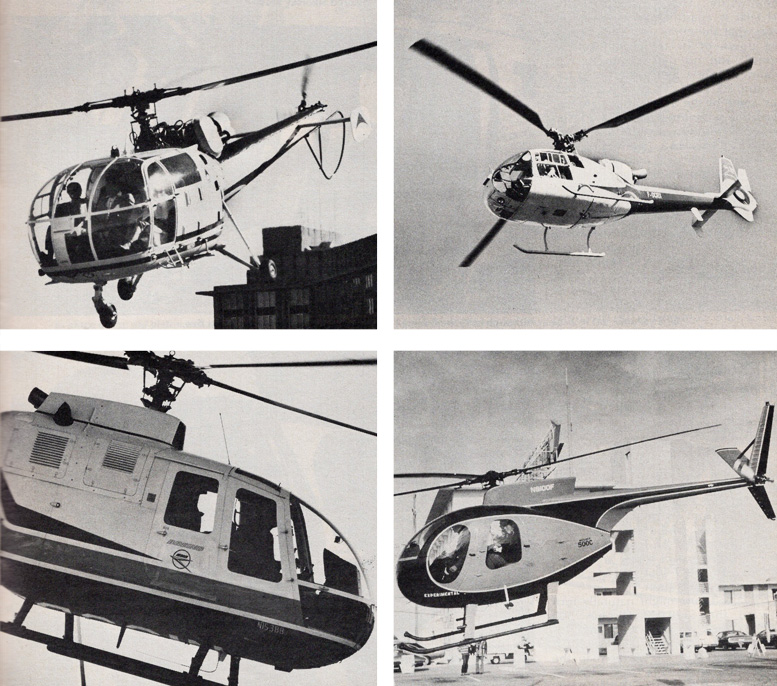

Tangled fortunes of twin-engine competitors: Boeing-Bolkow’s BO-1Q5C heads for the hills over Bell’s 212.

Its history is one of triumph followed by fizzle, succeeded by scientific breakthrough and trailed by technical delay. Give it another iota of speed, whack off just a few dollars here and there — and you’d have the superbird of the century. As it is, the helicopter is no slouch.

Aside from practically owning the offshore oil industry, it has performed heroically as everything from ambulance to gunship to aerial crane. Like Liza Doolittle, the helicopter has long since cast off its shabby rags and assumed handsome new trappings.

The animated-palm-tree, Erector-Set rotorcraft struggling to reach 90 mph has been eclipsed by a new breed of turbine-powered ships that look like a million dollars and go like gangbusters—compared with the old birds, anyway.

They make less racket, fly more smoothly, autorotate (glide) farther with an engine out, and with automatic throttles, their pilots needn’t fret about engine and rotor rpm. At this year’s big helicopter convention in Las Vegas, the parking lot of the Stardust Hotel was alive with new developments, new trends and new heroes.

For some, the new 400-hp C20 version of the Allison turbine engine was the big hero. It positively dominated the rotary-wing roster, powering not only the 206B JetRanger II, but the Hughes 500 and the twin engine Boeing-Bolkow BO-I05C.

“This engine is finally giving us the performance they were calling for with the old model,” said one operator, mindful of the fact that only 317 of those 400 horses can be used by the “airframe” (meaning rotor and transmission).

TOP LEFT & RIGHT: From France, the Vought-marketed Alouette III has wheels. The shrouded-tail Gazelle has speed.

BOTTOM LEFT: Boeing has hingeless, plastic unlimited-life blades.

BOTTOM RIGHT: The Hughes 500: exotic styling and maneuverability.

But with high temperatures and altitudes, the extra power (compared with 317 shaft hp of the old C18 engine) means a crucial difference between doing the job and pooping out. More important, the new engine seems to have nearly; erased the painful memory of early-model powerplants that gave operators fits a few years ago.

Rip Van Winkles returning to the helicopter scene after a long absence might be interested in the latest competitive rankings of the three U.S. rotorcraft using this same basic engine and spawned simultaneously by military competition in the ’60s. In its civilian role, the Bell JetRanger has far outdistanced the rest of the pack.

By the time this is published, the thousandth civil model will have been built and sold since the ship’s introduction in 1967. The Hughes 500, which came out in civilian form two years after the JetRanger, has been marketed to the tune of about 500 aircraft — not to mention some 1,600 military models.

Meanwhile, the Fairchild- Hiller FH-1100 is coasting on its inventory with what the company calls a “phasing down of its helicopter operations,” and no new production is planned unless new orders dictate. Around 200 FH-1100s were marketed, and some of the $99,250 birds are still available — with the older C18 Allison engine.

The rotorcraft was not represented at the HAA (Helicopter Association of America) meet in Vegas. The convention brought out the fact that engineers are tackling the old problems of helicopter longevity, vibration, speed and multi-engine dependability in interesting new ways.

With definite Mercedes overtones, the husky, rotund, German-built Boeing-Bolkow copped two of these honors, with twin engines and a rigid-rotor design boasting infinite life—a rare commodity in the helicopter world, where many components thrash and vibrate themselves into early retirement and must be replaced at the end of their carefully enumerated “lifetimes.”

A brief flight in the $308,000 machine (part of the Messerschmitt family) showed satisfactory single-engine performance. With one of its two powerplants out, the aircraft continues to cruise, if slowly, and lands perfectly—which is what you want most.

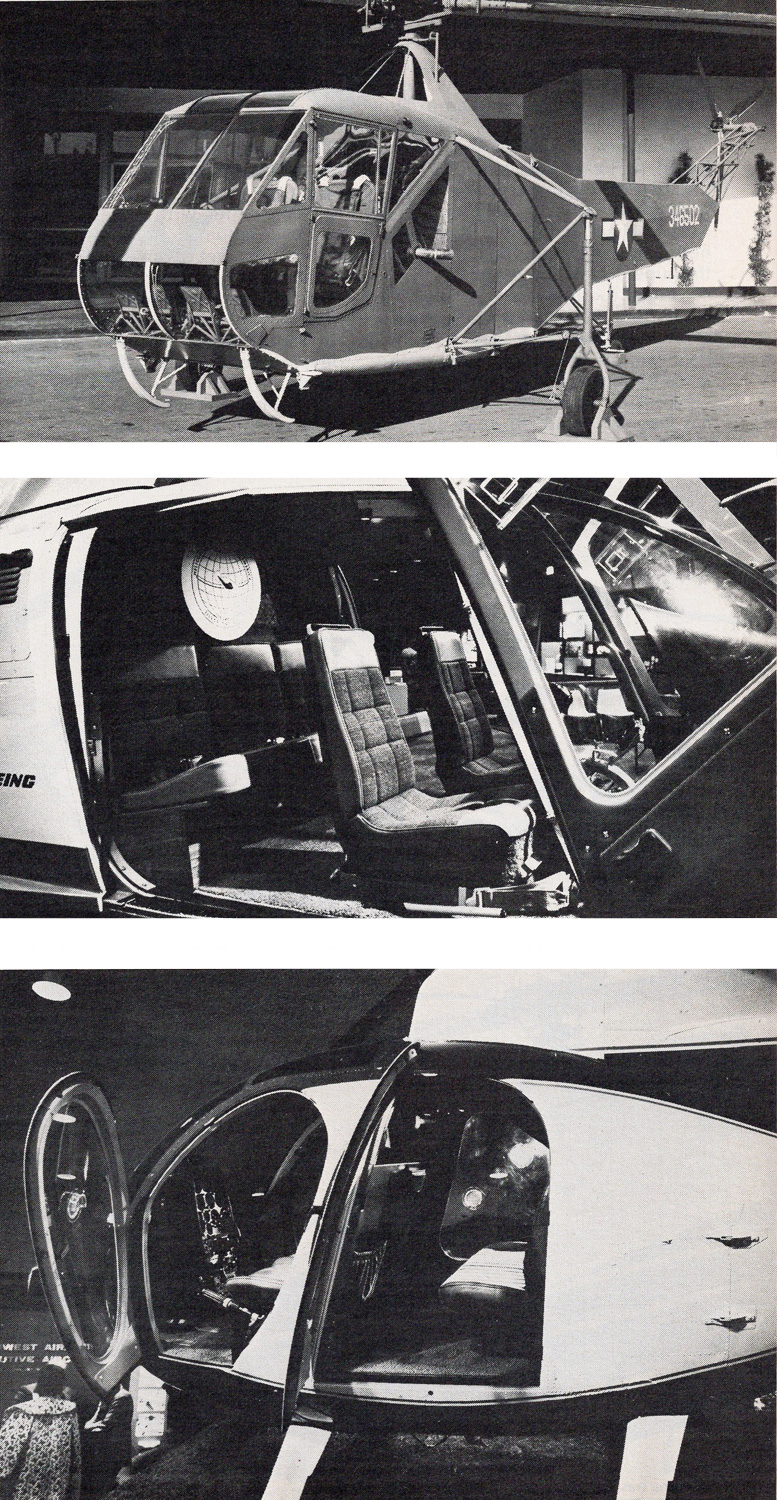

TOP: For nostalgia: Rick Helicopters’ restored Sikorsky R-4B.

MIDDLE & BOTTOM: Although both the Boeing (above) and Hughes 500 (below) seat five, Hughes baggage goes under the rear seats; Boeing has a rear cargo hold.

But don’t, of course, expect it to take off again on one engine, any more than you would expect a fixedwing aircraft to. And twin-engined or not, don’t expect to set any speed records — the BO-105C has a max cruise of only 144 mph.

For speed, one might naturally turn toward the $129,000 Hughes 500 ($10,000 less with the C18 engine). But though it appears terribly fast, it lists a max cruise no better than the Boeing-Bolkow’s 144 mph. In the speed-merchant class, the Vought-marketed French Aerospatiale Gazelle apparently flies off with top honors.

Equipped with a handsome shrouded tail rotor that probably cuts drag and obviously enhances safety, this $198,500 five-placer advertises a cruise of 150 to 160 mph — the highest of all the helicopters at the HAA meet. It also boasts an unusually high Vne (never-exceed speed, as in a dive) of 192 mph.

From time immemorial, vibration has dogged the helicopter. The new models manage to dampen it reasonably well, but as long as there are advancing and retreating rotor blades, an incessant bump, bump, bump in the cabin seems unavoidable.

There are fascinating tales of how vibration develops in regular waves along the frame of a helicopter, and how in certain models this mounting, or that accessory, would suffer chronic, inexplicable failures.

A bit of detective work invariably traced the problem to a point where the harmonic vibration was concentrated. Taking all this into account, Bell Helicopter Corporation plotted the vibration waves of their JetRanger like a big guitar string, and then devised a way to counter them.

They suspended the airframe from a beam below the engine platform at carefully calculated nodal points free of vibration and placed weights at certain spots to locate the vibration points where they wanted them. The result was a surprisingly smooth-riding JetRanger tagged “Noda-Magic” by Bell.

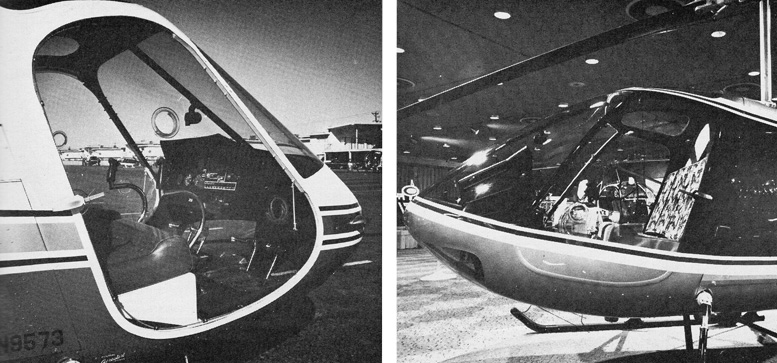

Latest evolution of the Enstrom F-28 (left above) is the 280 Shark (right above), with a sharper nose and narrower instrument console.

Although the company foresaw only a small penalty in terms of weight (60 to 70 pounds extra in a production ship versus 100 pounds in the test aircraft), no one seemed prepared to say when or if Bell would actually incorporate the system into the JetRanger or some other design, or hazard an estimate of the extra cost. For sheer size and strength, Bell’s 212 and Sikorsky’s S-58T dominated the scene.

With twin PT6 turbines and a cavernous, upholstered 13-place executive lounge, the 212 has to be the Rolls-Royce of corporate rotorcraft. This aircraft even received certification to fly IFR, but a great hullabaloo was touched off when Bell refused to accept it under the FAA’s attached condition that two pilots be on duty during IFR flight.

The company maintains that this would place an unnecessary staffing burden on operators flying instruments in areas of low air traffic density. Also sporting double PT6s, Sikorsky’s monster bird is more concerned with cargo heft. It will lift loads its predecessor H-34 couldn’t budge with its old radial-engine piston powerplant.

With a pilot, and half an hour’s fuel, the new machine will lift no less than 2½ tons of payload. Shining light of the smaller piston-powered helicopters at the meet was the Enstrom F-28, rendered even more handsome in an introductory version called the Model 280 Shark.

Discarding the full-width instrument panel of the earlier F-28, the 280 comes with a more conventional narrow pedestal. A pointed, slightly elongated cockpit gives the aircraft better-looking lines, and maybe even a few extra miles per hour, though the powerplant will continue to be the 205-hp Lycoming.

Under the deft husbanding of F. Lee Bailey, president and chairman of the board of Enstrom, the company seems to be exhibiting new marketing aggressiveness, backed by little fillips like Enstrom’s own insurance program for F-28 and 280 buyers.

But then, the entire helicopter industry seems to be enjoying lower insurance rates these days, with preferred-risk hull costs running as low as five to eight percent of the value of the aircraft. (Rates used to go as high as 20 percent, and 10 to 14 percent today is not uncommon.)

And neither initial prices nor maintenance costs have subsided in an industry traditionally plagued with high upkeep. Purchase prices of the turbine models are up a third or more from half a decade ago. But then, isn’t everything?

If they had their druthers, what would present helicopter operators like to see changed? Many ask for more size (about seven seats) coupled with greater speed (around 200 mph) and twin-engine reliability (something Bell’s proposed stretched JetRanger may offer in 1975).

Even with present aircraft, however, the industry appears to be thriving as never before, spurred by growing recognition that the helicopter will, after all, go places and do things no other vehicle can.

And with the spreading municipal tangle, the helicopter appears to be coming of age not just as a utility lift vehicle for inaccessible locales, but as an executive transport and hook-up with long-range fixed-wing fleets.

In place of the old piston radial, a Pratt & Whitney twin-pack of PT6 turbines nestles under the nostrils of the Sikorsky S-58.

Be the first to comment on "The Growing Swing To Rotary Wing"