Flying The Fields Of White

ARTICLE DATE: August 1989

Leaming to fly a helicopter in the Great White North is a challenging proposition. However, once the skills are mastered, the rewards can be great and personally satisfying.

Several stools away, a Noorduyn Norseman “driver” carried on a conversation with a low-time Cessna 180 pilot. Both were readily recognizable tor the airplanes they flew. The gray-haired Norsemaatype wore faded bush boots speckled with fish scales and moose blood.

Beside him, the Cessna “manager” sported mint condition running shoes with pink shoelaces and white stripes down each side. “Can’t be done. Can’t train no high-time fixed-wing man to fly helicopters,” snapped the Norseman.

Part of the training, almost immediately after first helicopter solo, includes hours of practicing elevated pad landings. Handling a sensitive helicopter can be tricky. In the field, rotory wing pilots are often called upon to land in areas with only inches on each side of the aircraft or less between trees and rotor blades.

Well, you see, sir, there exists the probability . . . the 180 began. Abruptly, he found himself alone as often happens when taxpayer-sponsored graduates from southern Ontario flying schools invade the north. Seasoned veterans never accept them until the day they hoist a 55-gallon drum of 80/87 shoulder high or wolf down a raw twelve-pound northern pike in thirty seconds.

As it happened, I, the subject of discussion, had remained out of sight in Red Lake, Canada’s Lakeview Restaurant. Word had spread across Northern Ontario that my employer planned to con vert some civil service pilots to rotary wing. Skeptics believed the task impossible.

Nevertheless, after years of flogging de Havilland Stoneboats (Otters) and Turbo-Beavers, I looked forward to flight training at Canadore College of Applied Arts & Technology in North Bay, 192 miles north of Toronto.

Shortly after unpacking my “Ontario suitcase” ie, a plastic garbage bag, I found myself staring into the cockpits of several of the shiniest “fling wings” I had ever seen. Quickly, I tried to psych myself into adapting to what a Canadore report termed a “delicately wristed, two-handed, double-jointed operation.”

My preparations had been intensive. Every word in print on technique and theory went into my notes. No working pilot who crossed my path escaped a grilling, and I watched every move of every helicopter that landed nearby.

Impatient, I once sauntered past a fire-fighting crew and surreptitiously filched a helicopter hat. Nonchalantly tilting it toward the back of my head, I felt ready to begin a reign as an upcoming rotary wing pilot.

Not overconfident by any means, I felt that despite almost 10,000 hours in aircraft with lifting surfaces securely bolted to a fuselage, I would learn quickly and easily. However, the possibility fixed-wing habits might hinder progress did not escape my mind. Worse, perhaps time in other airplanes had affected my coordination.

Canadore utilizes four Bell 47s and two Bell 206 JetRangers for flight training. Some critics suggested piston helicopters had little value since reciprocating engines no longer hamper the industry.

Others like Neil Laird, then president of Vega Helicopters in St. Andrews, Manitoba, argued Bell 47s compel students to be come better power managers. Mistakes cost less during starts and minimum damage occurs when trainees inadvertently exceed air craft limitations.

In my case, however, my employer requested all training be carried out on turbine equipment. During the first few days at the “Bomarc” or heliport seven miles north of North Bay, I noted many differences between instructors in helicopters and those in fixed-wing.

At home, I had worried about assignment to a freshly licensed time builder in tent on a loftier career. Fortunately, all Canadore’s instructors were “lifers.” None were “circuit aces” with no experience in the practical working world.

Chief flying instructor Wayne Bolen, for example, logged thousands of hours with several commercial companies. His colleagues, Colin Sullivan and Alan B. Lang, flew throughout Canada’s Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Quebec and Labrador.

Each summer Canadore closes for ten weeks and provides opportunities for their instructors to return to the field.

LEFT: Bell 206 helicopter instrument panels differ little in some respects from fixed-wing airplanes. Starter buttons and landing lights are on the collective lever between the seats. In the air, it usually takes many hours before high-time fixed-wing pilots become accustomed to control sensitivity.

RIGHT: The author (left) and experienced helicopter flight instructor Alan B. Lang spent almost a hundred hours together in Bell JetRangers and LongRangers. In recent years, Lang has flown a complex twin-engine Bell over Niagara Falls for a tourist-oriented company during vacations.

Several years ago, while renewing a fixed-wing instructor rating, a young pilot took great pains to prove his skills to the doddering old bird beside him. After this unpleasant episode, I resolved never to ride with anyone under thirty.

At Canadore, no one had anything to prove. When flight training commenced, I knew no instructor would jump on the controls at the twitch of a student’s eyebrow. As it turned out, tolerances for error were extremely fine.

Nevertheless, my mentor willingly let me take the helicopter to its absolute limits — an excellent way to understand these sensitive but versatile machines. Shortly after arriving at the Bomarc, a dilapidated one-ton top less truck croaked and wheezed its way along a service road near the gray-walled, yellow-doored instructor’s office.

A rust-crusted door flapped open on the driver’s side and I was suddenly treated to the august presence of a six-foot, two-inch ex-Toronto cop, ex-Royal Canadian Mounted Police constable and present part-time lumberjack. Alan B. Lang, with six helicopter types in his log book, would be my sole instructor.

Immediately, he dispelled another fear — assembly line instruction. This paragon of instructional virtue carried only five other regular Canadore students. Rotary wing flying begins with far more thorough preflight inspections than fixed-wing.

As an introduction to the fascinating language of helicopters, chief engineer John Hards provided stacks of mimeographed sheets detailing the walk-around. We spent most of the first afternoon absorbing terms such as swashplate, a two-plate system which slides up and down the main rotor shaft.

Pillow blocks were not soft feathery cushions as I had imagined but a pair of metal stops to prevent the rotor head from eating the mast. “Jesus nuts” had nothing to do with religious fanatics but held the rotor head on the machine. Lose one, a student remarked, and the pilot became religious but, depending on altitude, only for a short time.

Helicopters are subject to more vibration than fixed-wings. “Ships,” as instructors called them, possess annoying tendencies to loosen fittings, bolts, nuts, and locking wire. Shortly after completing the program, I overheard an A&P declare that helicopter and fixed-wing maintenance did not differ.

After scanning Bell LongRanger logs and noting a lack of discrepancies, he wrongly concluded no snags meant no maintenance. He neglected considering detailed helicopter preflights practiced by conscientious pilots.

“Long lining,” ie, threading a sling load down through thick bush is a cold, delicate operation since the pilot must have the door removed. Students at Canadore practice such work while building their winter survival training camp north of North Bay.

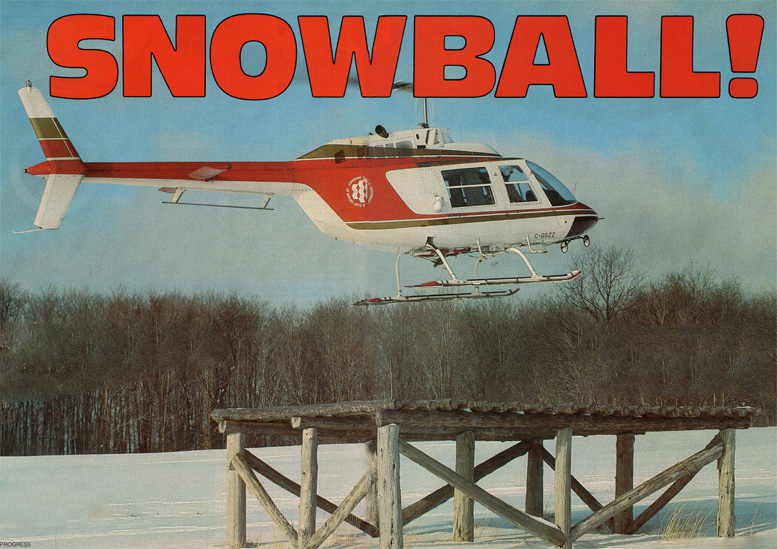

Most entries in my logbook would show the registration of C-GSZZ, a Bell Model 206B JetRanger-III. This utility craft weighed nearly 1800 pounds empty and carried approval for gross weights of 3200 pounds internally and 3350 with a sling load.

Powered by an Allison 250-C20B gas turbine rated at 400 hp but derated to 317 hp, the type first flew in 1966. Unstable in the hover relative to the older Bell 47s, the JetRanger has been rated an excellent instructional platform by most instructors.

Despite its reliability, the 206 has had a checkered past. “Sometime during the early years, almost every part of the 206 has either fallen off, cracked or worn.out,” said Lang. “Now, it’s one of the safest in the business and has been tested by thousands of hard hours all over the world.”

Helicopters do not possess many forgiving qualities nor are they aerodynamically stable. Light machines lack control trims to ease student-instructor workload. During my “psyching” phase, I frequently heard references to the sensitivity of hydraulically boosted controls.

Some pilots had also mentioned the Allison’s delicacy and its need for sharp monitoring during starts. The initial start came as a surprise. Accustomed to holding a de Havilland Turbo-Beaver’s switch for at least ten seconds be fore light-off, I jumped when the C-20 ignited almost the instant I rolled on throttle.

According to Lang, the turbine outlet temperature, or TOT, of most helicopter engines accelerates rapidly. Monitored carefully, few pilots overtemp the 158-pound powerplant.

Lang made the first liftoff and hover, then taxied toward a cement square behind the college’s maintenance classrooms.

Coming to a gentle stop, he carried out a flawless 360 clearing pedal turn each way. From the hover, he transitioned or moved ahead, into a gentle climb and pointed the bubble west of the Bomarc. In a few moments, and at a safe altitude, he relinquished the controls. Despite my mental preparations, JetRanger sensitivity still came as a surprise.

Later, 23-year-old student Keven Mulcair described it well: “The force on the cyclic and pedals would be equivalent to pushing a package of cigarettes across a tabletop with your fingers,” he said. Most helicopters have a stick called a “cyclic” which resembles a fixed-wing aircraft’s control column.

The cyclic changes pitch angle of each rotor blade once per revolution. In forward flight, it serves the same function as in a conventional airplane. Pedals are analogous to rudders and control yaw. A “collective” lever resembling a long automobile parking brake, to the left of the pilot, changes the pitch angle of all rotor blades simultaneously.

Raised or “up” collective increases blade pitch and thus altitude. The twist grip throttle of the JetRanger is at the end of the collective. Power changes require directional control corrections because of torque.

Pushing left pedal increases tail rotor pitch angles which pushes tail right, and right pedal reduces pitch for the opposite effect. Pilots must always fly with the right hand on the cyclic, and during training, the left stays on the collective. Feet cannot leave the pedals or the helicopter rotates rapidly out of control.

I found coordination very difficult, particularly while descending rapidly or during liftoff when the helicopter’s nose tended to swing. Several months before arriving in North Bay, a seven-day game patrol had taken me to Big Trout Lake, 375 miles north of Lake Superior.

One of my workmates had been riding in helicopters for over twenty years as a passenger and considered himself knowledgeable, if not expert, in rotory wing. Despite never having experienced a minute of flight instruction, he believed his opinions more sound than mine.

“You don’t got nothin’ to worry ’bout in them things,” he said. “They’s easy to fly and hov’rin’ ain’t gonna give you no problem.” How wrong he was. Lang returned the JetRanger to the Bomarc and began a placid hovering demonstration.

With almost 9000 flingwing hours and much of it on SZZ, he made the technique appear effortless. For a moment or two, I developed a fantasy that the expert in Big Trout Lake really did possess some knowledge of helicopter handling.

Ten feet above the ground, and only yards away from a picturesque hardwood forest, Lang casually placed one finger on top of the cyclic and smiled through the course, gray threads of his over hanging mustache.

“Now, this is all you require,” he said, as the helicopter remained precisely over a patch of poplar leaves between the skids. “Maintain a ten-foot hover. You have control.” The instant Lang’s hands returned to their usual relaxed position in his lap, the tree trunks outside the bubble disappeared in a whirling maelstrom of green and gray.

Dazed, frightened and tense, I felt the helicopter flounder downward, and I over-corrected frantically with up collective. Rotating wildly to the left and backward, we popped above the treetops where I managed to slam hard right pedal.

The machine staggered and halted for a millisecond or two, providing an opportunity for me to blink my eyes back into focus. In the time it took to return my lowered jaw upward to close my mouth, the aircraft whipped into a spin in the opposite direction.

Down collective, up collective, push pedal, adjust cyclic — I could not hope to contain the helicopter within the boundaries of Canada. “I have control,” Lang calmly said.

His fingertips reached toward the cyclic. His left arm showed a slightly perceptible movement, and the toes of his size 12 boots flexed. So quickly did the helicopter stop, my helmet slammed toward one side of my head and bashed my glasses down onto the bridge of my nose.

Groggy, baffled and white-knuckled, I took over again and uneasily fluttered away into a semblance of level flight. Eventually, Lang displayed the necessary patience required to “rehabilitate” a high-time fixed-wing pilot into rotary wing.

Repetition — constant repetition — enabled me to develop some illusion of controlling the helicopter in a hover. Step by step, Lang demonstrated more hovering, and soon moved into advanced hovering, ie, pedal turns over a spot, around a windsock, around the tail, etc. We then moved into autorotation.

Helicopter pilots are often asked about the ability of their air craft to survive engine failure. Lang assured me forced landings can sometimes be much safer than in fixed-wing. Caught with a power loss over a forest or boulder-studded ground, conventional airplanes meet the surface at speeds above stall with disastrous results.

A helicopter, if properly handled, touches down with zero forward speed. “In a power failure in a Bell 206, a freewheeling unit on the engine gearbox disengages the engine from the rotor and allows air flowing upward through the blades to provide lift,” Lang explained. “From the pilot’s viewpoint, the rotor acts like a wing.”

Canadore’s flight training manual compared the auto rotation to a parachute. As in fixed-wing, the pilot checks the area care fully. When the instructor calls “practice engine failure” and rolls off throttle, collective must be placed fully down immediately to maintain Nr (rotor rpm) between 90 percent and 107 percent.

If the student reacts slowly and Nr drops below 90 percent, the blades could fold upward and leave the mast. Above 107 percent, blades may fly away on their own private cross-country. Unlike airplane propellers, most helicopter rotors revolve surprisingly slow. The JetRangers turn at approximately 394 rpm, but have a tip speed of nearly 688 fps.

“Establish airspeed around 60 mph, but never more than 115. Watch Nr and wait. Between 50 and 100 feet, initiate a nose up attitude to convert airspeed to lift,” said Lang. “Wait again, and then at ten feet above ground, pull more pitch (collective) to further reduce the descent.”

Near the surface, the helicopter must be level. Ideally, the pilot will have up collective remaining to cushion touchdown which may be completely without forward motion or continued to a “run on landing.” As a fixed-wing pilot, I required much of Lang’s supervision to ensure my landings were not tail down as they were in float aircraft.

Fortunately, the JetRanger’s stinger prevents tail rotor strikes during training. Lang taught several types of autorotations. Engine failures were simulated during hovering and while taxiing a few feet above the ground.

He also showed techniques used during high-speed low- level runs and forced me into 180- and 360-degree turns with the throttle rolled back to idle. Most autorotations were preceded by warnings but complacency disappeared when the unexpected beep of the low-rotor warning horn went off in my helmet.

Often, Lang’s pace seemed too rapid, but hours of practice finally brought me to a point where I felt nearly as safe in helicopters as fixed-wings. Every practice took us to a “full-on” ie, actual touchdown, a procedure not always followed by less experienced instructors.

Lang reviewed emergency procedures constantly. He encouraged the reading of accident reports and through personal experience, described differences in helicopter makes. The remains of one brand had been stored in a disused Bomarc shed nearby. Lang pointed out the deficiencies of the type and strengthened my resolve never to ride or fly in one.

Accident reports often describe a danger unique to helicopters. “Dynamic rollover” occurs when bank angles build up beyond 15 degrees with one skid on the ground.

Despite full opposite cyclic and maximum engine power, a machine can quickly roll over. Pilots encounter this while working in muskeg or crusty snow. Attempting liftoffs with a skid mired or hooked may exceed critical recovery periods in less than two seconds.

“Recovery is simple — lower collective, but not in a panic or the main rotor will hit the tail boom,” said Lang. “To avoid dynamic rollover, the helicopter has got to be flown off cautiously and smoothly.”

My employer planned to operate helicopters year ’round. Fortunately, my training period at Canadore carried through winter as well as the snow-free season. Flying in snow or ice, stressed Lang, can be critical.

Most fixed-wing pilots dread winter overcasts when the nearness of the surface cannot be judged because of a lack of shadows and color contrasts. Conventional airplane crews can enjoy sunny days but helicopter pilots often create their own white-out.

Lang suggested watching Canadore’s other training machines and noting the cloud of snow or snowball that follows a helicopter as it approaches the surface. The object is to be down in a “no-hover” landing before the snowball overtakes the aircraft.

On liftoffs, hovering must be kept to a minimum. “Avoid white-out by using windswept ground where grass is showing,” suggested Lang. “In light powdery snow, you can hover high for a few minutes and blow it away before landing. It it’s really bad, pick a tree and follow it down slowly until you feel yourself solidly on.”

After skiplanes land, pilots have little reason to worry on level surfaces. However, helicopters can endure very little slope and tail rotors are sensitive to snowbanks. When a rotary wing machine tilts, the pilot may over-correct and find himself in dynamic rollover.

Sometimes, after throttle reduction, as the engine cools, snow crusts may give way and upset the machine. Lang suggested pounding the skids deeply into the snow by raising and lowering collective rapidly.

While operating fixed-wing airplanes, I occasionally found my self trapped in heavy snow and forced to watch large wet flakes drift into the engines or stick to the wings. Amazed at the Pratt & Whitney PT-6’s ability to ingest so much moisture, it came as a surprise to learn snow stops many helicopters.

Allison engines, described as superb by Lang, are small and have only one igniter plug. Canadore College’s Bell 206 JetRangers use particle separators to funnel foreign matter away from the engine and outside.

They also carry automatic re-ignition systems, which manufacturers claim alleviates flame-outs. When N1 or gas producer rpm falls below 55 percent, the igniter goes on before the engine spools down. Landing near snow-laden trees can be hazardous when rotor wash blows snow into the intakes.

After a week of daily instruction, Alan B. Lang finally suffered his first and only lapse from reason and sensibility. After we landed for the eleventh time in thirty minutes, he opened the door and stepped outside. A safe distance away, he obviously planned on watching some kind of spectacular airshow.

As I idled the 33-ft 4-in blade swirling a few feet above my head, the market value ($600,000) of a Bell JetRanger crossed my mind. The fact my employer had invested a considerable sum in my training and would not appreciate paying for a “modified” helicopter weighed heavily upon my decision to go alone.

It did not help that every student at Canadore was half my age. Worse, I had already thudded the helicopter into the ground during the last four landings. Lacking enough courage to shut the machine down and tell Lang this could be done another day, I slowly raised collective.

Anticipating a yaw as the machine became light on the skids, I neglected to notice I held the cyclic too far to the right. The left side came off the grass at a terrifying angle. Accident reports, photographs I had seen and warnings flashed through my mind — damn, dynamic rollover!

I quickly “dumped” collective jolting the helicopter level. I had not even left the ground but in the space of a few seconds, nearly terminated my rotary-wing career.

Again — collective, and again, very slowly the machine lifted off and this time separated from the surface in a somewhat level attitude.

Almost immobilized with terror, I could not per form the customary 360-degree clearing turn but staggered straight ahead. Several seconds later, I closed my eyes and plunked it on the ground. Not bad — short but a first solo. Encouraged, I again lifted off, cautiously turned completely around and flew an entire traffic pattern.

From this point, learning progressed much more rapidly into advanced dual and extra solo. Fad landings with little room to spare on each side of the skids became routine. Touchdowns under tree canopies followed by “towering takeoffs” at full power took considerable time to learn.

However, Lang knew that after almost 10,000 hours of staying away from trees, time would be needed to recondition my survival instincts. Never impatient or sarcastic, he dissolved many doubts through repeated practice. Eventually, the college arranged a flight test with Transport Canada (ie, Canada’s FA A). Examiner Dan Danford arrived in North Bay.

After a thorough ground briefing, we departed the Bomarc. Slightly over an hour later, we returned and he authorized an “alternate category en dorsement.” Danford’s final words, as he slipped into his blue government limousine — “You’ve got a license to learn” — were the same ones I had heard from another examiner who granted me a commercial pilot license centuries ago.

During my accelerated eleven-week course, I examined the entire Canadore College flight training spectrum. Competition for the few places available is keen. At least 100 applications cross the chairman’s desk each year. Candidates must be at least 19 years old and have Ontario Secondary School Graduation Diploma or equivalent.

Ontario residents over 19 without diplomas may be accepted on the basis of mature student tests. Unfortunately, admittance is restricted to Canadians. “No one’s considered unless they have a private license at the time of application,” said chairman Ross Lindquist, who retired shortly after my departure from the college.

“Besides language and math tests, we administer a 30-question exam on aviation knowledge but make our final decisions based on personal interviews.” Canadore’s flight instructors usually conduct the one-on-one interviews. Each applicant must convince the staff of more than a simple desire to fly helicopters.

They need to prove they possess a basic understanding of the aviation industry. Too often, helicopter pilots throughout North America find their careers far less glamorous than they originally perceived. Hours are long, work seasonal and Canada, in particular, has some of the cold est, highest and hazard-loaded terrain in the world.

“If someone’s talked to potential employers and looked realistically at their chances of finding work and still want to continue, they stand a chance of scoring well,” said instructor Colin Sullivan, a graduate of 1972. “People dropping by to look the pro gram over generally rate highly also.”

When Canadore initiated helicopter training in 1971, only six graduated. By May 1989, over 250 were awarded Canadian commercial helicopter pilot licenses. Many hold key positions in industry and others crew air ambulances or police helicopters. Four Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources pilots passed through and now fly hundreds of hours every year without incident.

Students spend 34 weeks from mid-August to early May flying 50 hours on Bell 47s and 50 on turbine equipment. Additional time can be purchased at market rates. Most solo after ten to twelve hours and acquire enough time to pass Canada’s requirement for a private helicopter endorsement by mid-January.

Before an FAA-equivalent flight test, they write a 60-minute, 50-question exam, and are monitored in the air by all instructors. Later, a much more detailed 100-question, three-hour commercial pilot exam will be written before year end.

In my case, a selection process for admittance to provincially – sponsored Canadore College was not necessary. My employer — also a branch of the Ontario government — had decided to sell some fixed-wing airplanes and integrate helicopters into the fleet.

Instead of finding “redundant” stamped on a pink slip, I and several other pilots slid into helicopter training. Many tasks ahead resembled those I enjoyed as a floatplane pilot. Animal surveys, railway inspections, and flights as mundane as searching for gravel pits would comprise the bulk of the work.

As experience accumulated, I would undertake fish planting, game patrols and later, fire-fighting duties such as drip torching. Several weeks later, while visiting family in Red Lake, I sneaked into the Lakeview Restaurant.

Unsure of my status now as a flingwinger, I learned the Norseman pilot who had spoken months before would not return for weeks. Some “turkeys” (ie, tourists) had talked him into a month-long charter to Hudson Bay.

Grudgingly, the boys accepted round after round of refreshment. With the generosity befitting a civil servant, I cheerfully reached for my wallet again and again. This time, as I deposited a resplendent tip upon the outstretched palm of the waitress, I took a second or two to reflect on my aviation career.

The hours had been mostly pleasant ones and each logbook entry sparked fond memories. Now, with a fresh license and renewed limitations, I looked forward to an exciting new field.

Fixed-wing pilots are often surprised to find Canadore College uses a Bell 47 on floats during the winter. The wide footprints make for snowshoe-like landings. This type of machine has almost disappeared in Canada but a few are used for training and special patrol contracts.

Be the first to comment on "Learning To Fly A Helicopter – In The Snow!"