There are a lot of new helicopter pilots out there and I thought that some of you might benefit from a few words from an old time RotorWay flyer. When I took my Phase 2 training at RotorWay we only did a couple of autorotation practices and then I was signed off for solo flight within my practice area.

Returning home with my new solo-to-altitude endorsement it was time to get airborne. At this time I had around 50 hours of hover time on my RotorWay so I was pretty comfortable. Set the ballast weights correctly, went through a very complete preflight, used the restroom, checked the ballast weights again and finally ran out of excuses.

It was the hour of reckoning: this is what it was all about!!! I was scared spitless!

As I sat in my helicopter hovering at 24 inches altitude over the helipad, I felt real secure. What had my heart pumping and my body sweating was the thought of leaving the security of the hover and actually going high enough to get hurt and of being all ALONE without my flight instructor to make sure of that safety.

Finally the command, “c’mon wimp, go for it”. The take off was beautiful and I had flown for at least 40 seconds when out of the corner of my right eye there was a movement.

The Velcro-attached seat cushion (they were about 12” square in those early ships) had become un-Velcroed and was lying on the passenger seat. The voice of Stretch immediately hollered, “Make sure everything in the cockpit is secure before flight so that nothing flies out the door and into the tail rotor”.

STAY! I thought as loudly as possible, but that cushion had its own agenda.

Slowly it moved toward the door opening, I had to stop it but was 200 feet in the air, what to do? First I tried holding the cyclic with my knees so that I could just very quickly grab the cushion.

As soon as the cyclic death grip was released, the helicopter dipped and I had to grab it immediately. Next I tried to stay in a left banking turn but the wind caught the cushion and out it went – just knew I was dead meat. Miraculously the cushion missed the tail rotor and I was still flying.

Headed for home where my wife was still videotaping this first flight and found a problem. Our property was only 150-feet wide and I had only made landing approaches onto the two mile long runway at the RotorWay School.

Stretch always said, “Keep that airspeed near 60 mph throughout your approach, until you have to slow down, that way you are always ready with enough airspeed to do an autorotation and flair in the very unlikely event that the engine should fail”.

I tried and ended up doing a beautiful low altitude fly-by, just missing the neighbor’s antenna in the process. This happened several times until I just slowed at around 100 feet. Sorry Stretch, but I needed to use the restroom.

I then just did a full power descending hover to the pad and parked it. My wife said she had gotten some great footage of my flybys and then wondered why I was sweating so profusely in the middle of January.

The thought that took all of the fun out of the solo flight without a flight instructor was, “what if something breaks or quits, I have too much money and time invested in this helicopter to have it or me damaged”.

I think this thought has occurred to most of us at times and is most likely one of the reasons we see so many RotorWays for sale with very low time. The decision was made right then and there that to obtain more training in autorotations.

My good friend, the late Bill Cunningham, and Steve Lewis who, I believe, is still active in the Sierra Rotorcraft club, were at RotorWay for Phase II training. During a practice auto in which Bill was at the controls in the factory ship 56Tango, the instructor noticed that the engine had failed.

The instructor took the controls and finished the auto, sans engine, to the runway. There was a problem though. This instructor had never done a touch-down auto in the RotorWay, only in Robinsons and as often happens, the helicopter rocked forward and then onto its left side totally destroying itself in the process.

This happened several times to the factory helicopters that I know of and is something to be avoided with my ship. I should tell you that both occupants emerged through the kicked-out front windscreen without a scratch. Steve Lewis did a show-and-tell at our next club meeting with the photos he took at the scene.

After many phone calls and references I located a flight instructor who had built two of his own RotorWay helicopters and was presently flying the surviving one. He had experienced an engine failure while touring with his wife. After doing a beautiful autorotation and flawless run-on landing he crashed the helicopter, destroying it.

It seems that after doing everything right the helicopter tipped up on the front of the skids and then rolled over onto the left side thrashing itself to pieces with the main rotor blades.

This fellow was a friend of Bob Thorensen, who was at that time RotorWay’s test pilot. Bob had numerous times performed touchdown autos with the RotorWays without hurting himself or the ships.

This flight instructor, Jim Sergaser, asked Bob how to do a proper RotorWay touchdown auto. Bob told him that RotorWays had the nasty habit of wanting to rock forward (due to a high center of gravity and short front skid extension) and then to the left when they contacted the ground with any forward motion.

He said the “trick” was to repeat to yourself, all the way down, “make it stop, make it stop!”

The idea is to hold the final flare at the bottom of the auto long enough to completely stop all forward motion of the helicopter, before leveling the ship and then setting it down with zero-mph ground speed. Without forward motion the helicopter will not rock forward onto the skid tips and roll over.

Dan Van Duesen and I together, hired Jim to teach us autorotations and we did hour after hour of them until they became second nature. About six months later the time came to prove the concept. Dan and I were flying Wayne Berry’s beautiful Scorpion II at about 250-feet altitude when the engine quit.

Jim’s instruction to us paid off as we executed a 90-degree turn into the wind and set the little helicopter down without a scratch saying “Make it stop” all the way down. We found that the single ignition coil had failed so I hiked home and got another one, installed it, and flew the helicopter home.

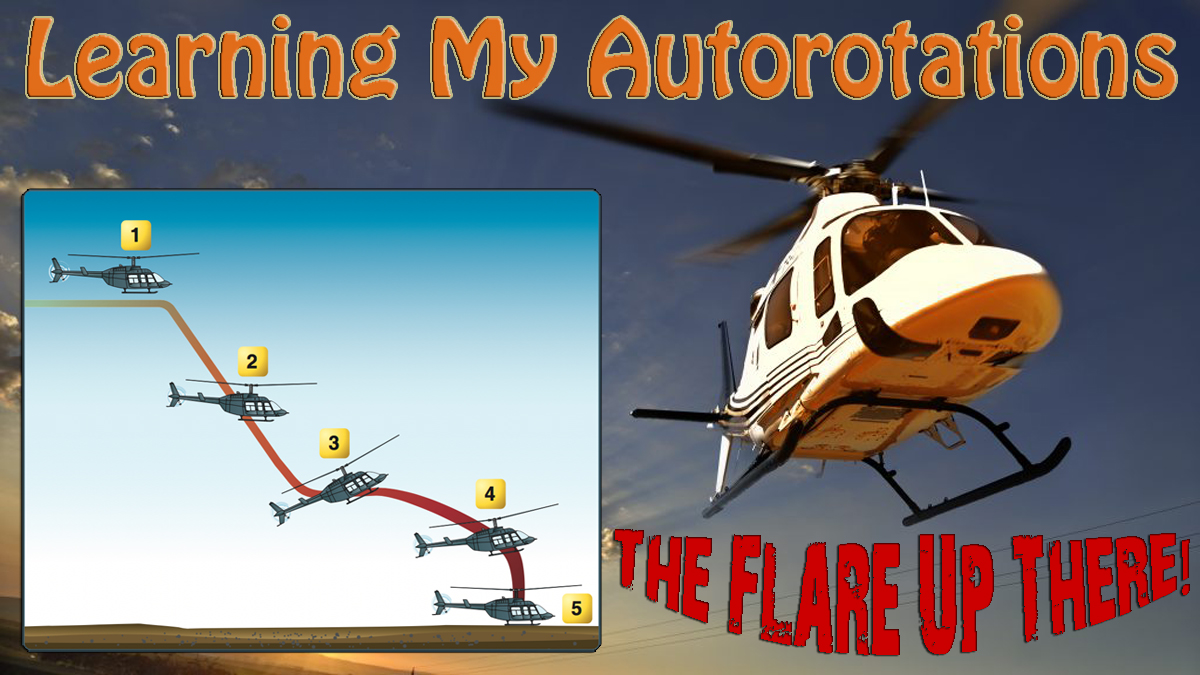

The practice procedure was to go up and do about an hour at a time of autorotations from 500-feet. When the flair was completed, the helicopter was leveled and power was applied. The forward motion of the helicopter should be zero. With many hours of practice we just got better and better.

It helps to have someone present initially that knows how to do a proper RotorWay autorotation so they can critique your performance and give pointers. I made it a habit to do at least five autorotations each time I would go out for an hour of flying.

I also was constantly aware that at any time it might be necessary to actually do one for real; there is usually no warning, it just happens and you have about a second to react or you are in a heap-a-trouble.

The Helicopter Adventures Inc. flight instructor course was very intense. They believe that every graduate of their flight instructor school should be qualified to teach in their own flight schools. We did no less than 50 to-the-ground autorotations.

It is quite unnerving to take a perfectly flying helicopter and cut power, knowing that it is not coming back on unless you really mess up the procedure. We always landed into the wind and with several knots ground speed. I got pretty good at it, I thought.

Due to the FAA examiner going ground hog hunting during the time I was ready for the Practical CFI exam I elected to arrange to take it once at home since there was a local rent-able helicopter for that purpose. After passing the five hour ora) exam for the CFI rating I was ready to fly.

The flight portion of the CFI practical test went without a hitch until the examiner asked me to land and exited the helicopter prior to having me do the touchdown auto. I had never done one in a Hughes 269B (HAI uses Schweitzer 300CB’s), never in any helicopter solo and to top it off the examiner wanted to view it from the ground and at a safe distance.

As it turned out the Hughes 269B has low inertia blades compared to the 300CB. It is flown solo from the left seat while the Schweitzer 300CB that I trained in is flown solo from the right seat so everything was a bit different.

The other factor was that at HAI I always had performed the touchdown autos into the wind with my master instructor for ballast and on the day of the check ride here in Missouri the air was dead calm. I did the auto, but without the wind I was going too fast approaching the 30-foot circle in which it was necessary to stop.

To slow down I did a rather radical flair (ala RotorWay) and then leveled the helicopter with the collective still firmly in the pocket. Before raising the collective it was obvious the helicopter was sitting squarely on the ground, no bounce, no slide, it had just rotated forward and set perfectly and lightly like a feather.

I was a bit unsettled as I had not had the opportunity to complete my part of the maneuver because the helicopter had already landed and the collective remained firmly in the down position.

Exiting I was greeted by both examiners (I was honored to have an FAA examiner in training watching the entire test along with the examiner who was giving it) and the owner of the helicopter, saying it was one of the neatest and cleanest touchdown autos they had seen and I was appropriately congratulated and passed on the PTS.

What actually happened was that although I was flying an unfamiliar helicopter from an unfamiliar position with no wind, once again training took over when it was needed with the result of a near perfect RotorWay set-down with no forward motion. Some habits are hard to break and that is one not to let go.

The real point is that you all have a small fortune tied up in your helicopters. Be sure to practice your autos until you feel very comfortable doing them and your power recovery flares are smooth and right.

When you level off, the helicopter should have zero-mph ground speed. Both Robinson and Schweitzer teach that some ground run is acceptable but it is not quite the same in the RotorWay.

Always keep in mind; it is not “if an autorotation will be needed some day, but when”. Always be ready for it, keep a landing spot within reach at all times, fly over open areas when ever possible and if not possible climb to an altitude that will allow a safe auto to a safe landing area.

Train by doing practice autos regularly and you, your passenger and your helicopter will come out in one piece.

Nice article! I was lucky enough to experience a full touchdown auto with Stretch at the controls !!! Looked simple,but probably wasnt …But Stretch could probably fly a coffee table

Would extending skids longer forward help with Rotorway NOT wanting to “Flip” over on landing from “Auto-rotation.”? (Just thinking out loud).

I’m sure this has been discussed somewhere on a forum before but basically, run on landings would benefit from longer skid for stability, but then there is more contact to possibly catch if not controlled correctly. The newer models have wider skids for landing stability, but nothing beats avoiding common pilot errors such as entering a vortex ring state or similar where it is avoidable…