Affordable Helicopters For Everyone

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO “A Helicopter In Every Garage?”

ARTICLE DATE: November 1978

THAT ERA MAY NEVER COME – BUT THE NUMBER OF “PERSONAL HELICOPTERS” IS ON THE RISE

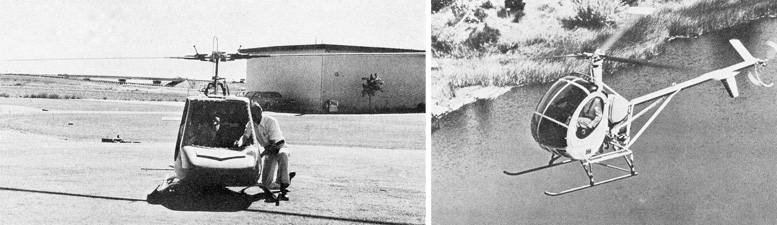

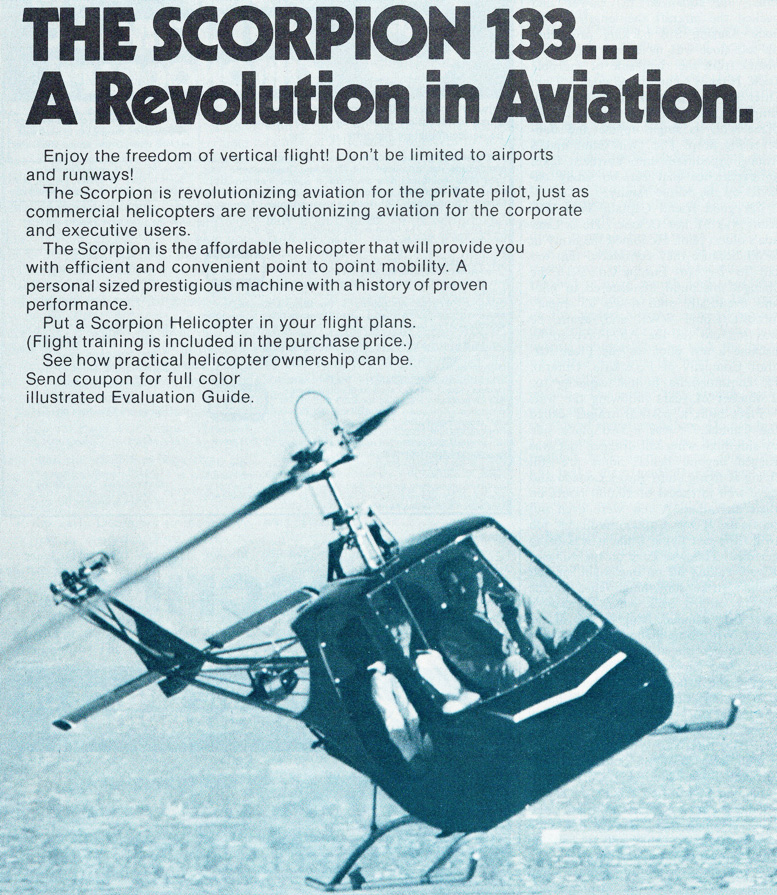

LEFT: B. J. Schramm, designer of the Scorpion, checks Peter Lert out in the diminutive homebuilt.

RIGHT: The Hughes 300C remains a mainstay of the commercial light reciprocating engine powered helicopter market.

REMEMBER THE helicopter fever of the immediate postwar years? The chopper was a brand-new aircraft then — a wonder machine that could cruise as fast as many light planes, yet land and take off vertically in a space scarcely larger than its own rotor diameter.

The press — both aviation and general — was filled with glowing reports, helicopters appeared in urban skies carrying mail between post offices, a few large cities even had regular helicopter airlines linking the civic center with the airport . . . there was even a popular television series, “Whirlybirds,” about the exploits of a couple of rugged crime-fighting types and their trusty Bell 47.

Inevitably, predictions were made that helicopters would become as cheap as autos, that everyone would learn to fly one, and — yes — that there’d soon be “a helicopter in every garage.”

What happened?

Why aren’t the skies black with little helicopters taking Hubby to work, the kids to school, and the little woman to the supermarket or hairdressers? Why don’t we hear “Dad, can I have the keys to the chopper tonight?”

Is it because helicopters are too difficult to fly? Because the air-traffic control system would become too complex? Because of zoning restrictions?

No. While the above problems would become real ones if helicopters were to proliferate the way we thought they would in the fifties, the real reason we don’t see more helicopters nowadays is a simple one: they’re too damned expensive.

Now, this bald a statement is sure to arouse cries of protest from those of our readers who are involved in the fling-wing segment of our industry.

They’ll rush to point out the myriad areas in which helicopters have become indispensable: urban police patrol, traffic and news reporting, maritime search and rescue, oil exploration and development, flying cranes, medical evacuation—the list goes on and on, not to mention such public-spirited projects as the recent unpleasantness in Vietnam.

In each of those cases, though, the helicopter’s usefulness and unique capability — that of hovering motionless, of taking off straight up and down — have been so important as to outweigh its inherent expense and inefficiency.

Just how expensive and inefficient?

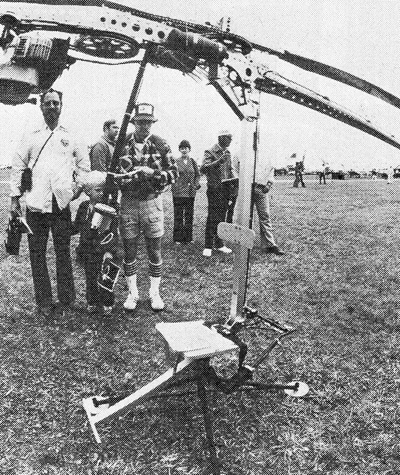

This ultralight foot-launched helicopter hadn’t yet flown when this picture was taken. Power is a 12 hp chain saw motor; landing “feet” are for training only.

Let’s take the roughest possible look at some figures — and please bear in mind from the outset that we’re not badmouthing a particular helicopter (or, for that matter helicopters altogether), we’re just comparing it, dollar for dollar and horsepower for horsepower, with a fixed-wing aircraft.

We’ll use the Grumman American Tiger as the fixed-wing candidate, comparing it with a Hughes 300C helicopter; both use essentially the same powerplant, with the helicopter installation delivering 190 hp (compared to 180 for the airplane) by running at higher rpm.

The airplane costs $29,260, the helicopter $69,900; the airplane carries four, the helicopter three; the airplane cruises at about 160 mph, the helicopter about 90 or less; – useful load is the same, at around 1000 lbs.

Doesn’t look too good for the helicopter, does it—but then, the Tiger, excellent aircraft that it is, doesn’t take off vertically worth a damn. The point I’m trying to make here is that you pay a lot for the way you negotiate those first (or last) 50 feet of altitude—enough so that most folks still stick with the stiff-wing birds that need airports to fly from.

“So why are helicopters so expensive and inefficient?” I hear you cry. “Surely they aren’t that much more complicated than fixed-wing ships.” Ahh . . . but they are, unfortunately, and that’s where much of the problem lies.

Let’s just look at the power plant, to start with. There’s hardly a simpler engine installation than that of an airplane.

Step 1: bolt engine to front of airplane;

Step 2: bolt propeller to front of engine, letting it revolve at the same speed as the engine output shaft.

Now, let’s look at the helicopter.

Step 1: Bolt engine—usually a non-standard type designed to run vertically, which requires a special oil system with a scavenge pump and so forth—to airframe.

Step 2: since there’s no propeller blast, and you can’t depend on airspeed for cooling (there may not be any when the engine’s working at its hardest, in the hover), arrange some sort of fan or blower.

Did you remember to make the engine big enough to handle the horsepower needs of the blower — and they’re significant — above and beyond the needs of the helicopter itself? Good — you’ll find the extra few thousand dollars for another 15 ponies well spent.

Step 3: Add some sort of transmission to reduce the engine speed to a suitable speed for rotors. It’s up to you whether you want to use gears, belts, or a combination.

Step 4: Ooops — almost forgot! What if the engine quits? In an airplane, the propeller just stops, no big deal. In a helicopter, you don’t want a failed engine to lock up the rotor, so you’d better add a clutch that’ll kick out automatically – and you may need another one to engage the rotor system when you start the thing up.

Now you’re pretty well set as far as power is concerned, and you can start considering how you’re going to install the rotor and control each blade individually while they’re thrashing ’round and ’round. And speaking of ’round and ’round, don’t forget a tail rotor, or that’s what your flight path will be.

You’ll have to make all these components as light as possible, too, or the thing will never fly — so light, in fact, that you’d better plan on some of them, like the transmission, wearing out in a few hundred hours . . . are you starting to get the picture? Not that the efficiency of helicopters hasn’t improved a great deal over the years.

What’s unfortunate for those of us who still want one in our garage is that many of the most significant advances have been made on the larger helicopters, and are only gradually trickling down to the range of “garage” ships; even the very cheapest light commercial helicopter nowadays will more than ruin a $50,000 bill.

In fact, as long as we’re talking about cost, let’s look at a few figures. One cost that few prospective fling-wing buyers seem to consider is the cost of learning to handle the thing in the air.

Obviously, any outfit in the business of teaching helicoptering has to make at least a modicum of profit at it; given the fact that the helicopter is more expensive to operate than a fixed-wing aircraft of similar capabilities, you can expect to pay commensurately more for training.

While there are a few flight schools that use small ships — usually Hughes 269s — for training, renting them out at around $65 per hour, most still use the Bell 47, which nowadays goes for between $85 and $110 per hour.

Add to this the cost for an instructor, at $12 to $15 an hour, and you’ll see that even at the low end of the scale it’s hard to get away for less than $80 per hour. If you’re going for a private, you’ll need 40 hours, much of which will be dual—count on about $3000 as a minimum.

Even if you’re just adding a private to an existing fixed-wing ticket, it’ll take at least 25 hours, almost all of which will be dual; the bite will be $2000 or worse. Another point to consider is maintenance.

The old saw about helicopters spending a couple of hours in the shop for every hour in the air is no longer true; even the older Bell helicopters and Hiller helicopters probably fly at least twice as much as they’re worked on, time-wise.

Newer and/or smaller ships come off even better, but the fact remains that you’ve got to budget a reasonable amount of time — at about $20 per hour — for routine maintenance.

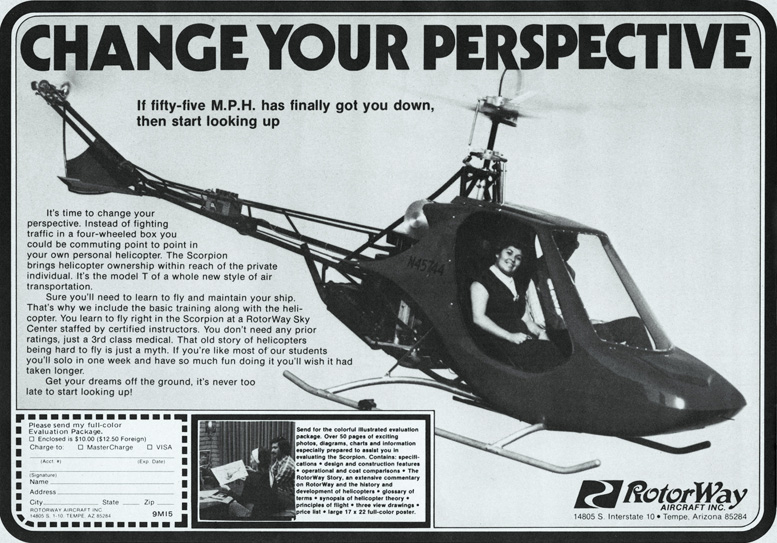

The Hillman Hornet is available as a kit for do-it-yourselfers: it’s a descendant of the Helicom Commuter, uses a 150 hp Lycoming.

Most light helicopters do best if they get 25-hour inspections, or at least 50-hour inspections, rather than the usual 100-hour jobs; the parts in a helicopter are simply stressed highly enough so that they bear close watching. Figure on $7.50 to $10 per flight hour for maintenance, unless you do your own.

Remember, too, that there’s a parts wear out allowance to consider: say your transmission is good for 500 hours, and a rebuilt one will cost you $3500; you’ve got to budget $7 per hour for that component alone.

These factors may not necessarily rule out the idea of the personal helicopter — after all, there are lots of airplanes used as “personal” craft nowadays that have similar operating expenses, and cost a lot more initially than a $50,000 helicopter, but they may require some justification for a “personal helicopter.”

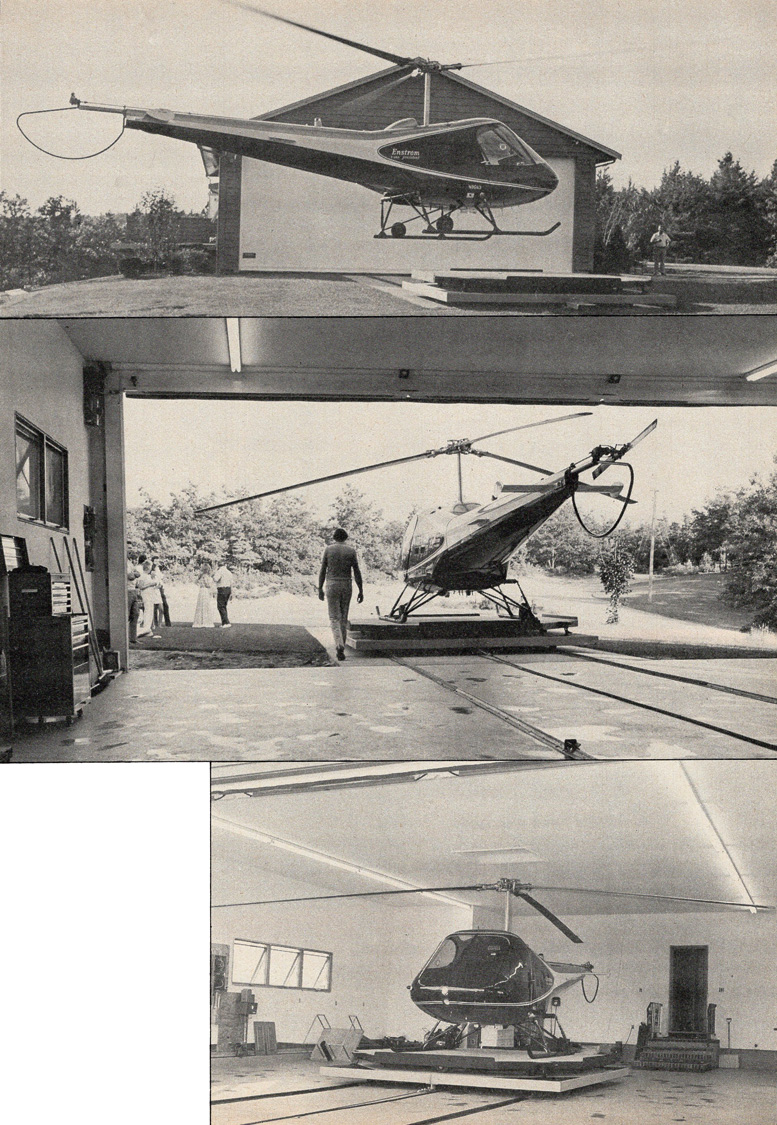

The Enstrom F280C is the prettiest, fastest, and most expensive among the light helicopters currently In production.

It’s a matter of preference and possible application — after all, lots $50,000 airplanes sit around almost all the time, flying only a few. hours, so there is a chance that a helicopter could prove useful even if opportunities for its use are relatively limited.

If your travel needs center around relatively short distances— say not more than 300 nm — and if it’s a hassle for you to get to the airport from either your origin or your destination, a helicopter may be just what the doctor (or lawyer, or banker, or real estate developer, or similar well – heeled professional) ordered.

Got a weekend retreat in a remote area that’s not at too high an altitude? Does your job take you to such places as construction sites or outlying offices that aren’t close to airports?

As long as your primary objective isn’t to fly far, fast, or high, a helicopter can be very attractive — and renting an airplane for occasional long flights is a lot cheaper than renting a helicopter if you own an airplane.

Finally, it must not be forgotten that light helicopters are an absolute gas to fly; not a few $50,000 airplanes are flown almost entirely for recreation, and there are probably those who’d be game to spend a similar amount on a recreational helicopter.

Very well — granted that this still doesn’t mean a helicopter in every garage, let’s have a look at what’s available in the way of relatively affordable light helicopters. Basically you’ve got three alternatives: buy a new light helicopter, buy a used one, or build a very light helicopter from a kit.

Buying a new ship is unfortunately not a subject that need be covered at great depth, since there are only three basic choices available at present, (There may soon be a fourth: Robinson Helicopters is completing certification of a lightweight R22 2-place, which is designed to compete in both acquisition and operating cost with the Cessna 172.)

The smallest and cheapest is the Brantly B2B, a two-place that lists at $49,950. The other two entries, Enstrom and Hughes, are nominally three place machines, although both of them get a bit snug with three up — particularly the latter.

The Hughes is more utilitarian, retaining much of the “mosquito carrying a flashlight bulb” appearance that has long been associated with light choppers; the Enstrom, which is almost invariably ordered with a turbocharger and is a bit faster, is quite a bit sleeker.

One version, the F280C “Shark,” was listed in last year’s “Fortune” magazine as one of the 50 best-designed U.S. products. Plan on spending about $70,000 for a Hughes 300C, about $86,000 for a turbocharged Enstrom F280C “Shark.”

All three of these helicopters are handy personal machines; they’re also ideal trainers, which may be a point to consider if you’re thinking of leasing them back to a flight school. All three of the helicopters just mentioned are also available used, of course, and so are some others.

Probably the most common is the Bell 47, the classic “Birdcage Bell” (so named because of the girder construction of the tailboom) that is still considered the light helicopter.

Various models are available at prices from $30,000 to $50,000 or more; older “D” models have unboosted controls and build strong bodies twelve ways—you can feel every bit of grit or dust in the main-rotor swashplates right through the stick.

The more desirable “G” aircraft have hydraulic boost on the cyclic and, in some cases, the collective Controls; the costly G3 types are turbocharged for high altitude or hot temperature work.

You’ll even find a few “J” ships, or “Rangers;” these are executive transports, in which the standard three-abreast bench is replaced by a different fuselage arrangement for three passengers on a bench while the pilot sits ahead of them in lonely splendor on a central single seat.

All the Bells are very pleasant to fly, and perform quite well, but count on a good deal of maintenance, particularly on older birds; parts, including limited life components like transmissions, tail rotors, and metal main rotors (wood blades on the older ships have no fatigue limits!) have to come from Bell and cost plenty.

Another used ship to consider might be the Hiller E-2 or E-4 series, both of which were civilian outgrowths of Korean-war era military ships. Both are rugged, roomy—the E-4 is a four-seater — and can be had with turbochargers; as in the case of the Bell 47, you can expect to part with a pretty penny for maintenance and parts.

Rather than using hydraulic boost, the Hillers use a pair of “servo paddles” which rotate with the main rotor; the paddles are controlled by the pilot, and they in turn control the rotor for light stick pressures at the cost of a bit of lag in the response time.

There is also a five-place version of the Brantly, and while it’s not really in the light helicopter class, used ones occasionally appear at light-helicopter prices.

In appearance, it has the same recumbent-ice-cream-cone aspect of its smaller counterparts; it sports such big-ship features as wheel landing gear and hydraulic boost on the cyclic. Although no new Brantly 305s have been built for some time, the Brantly factory in Oklahoma continues to provide excellent parts support.

If you don’t mind flying a rather rare bird, it’s a lot of chopper for the money. Finally, if you don’t have to carry heavy loads, and if you enjoy working with your hands, you might consider building your own helicopter.

It’s not a project to undertake from scratch unless you’re a helicopter designer and a skilled machinist, but at present there are two complete kits available for small two-place helicopters.

Since both of these would be experimental air-craft, they can’t be used for hire in the strict sense of the word — that is, no leaseback or passenger carrying for hire, and experimental ships also can’t be used to give dual instruction required for a helicopter rating.

On the other hand, a homebuilt helicopter can legally be used in furtherance of a business. The two kits that are available are the Scorpion II helicopter at $13,500, which was covered in Air Progress for August of this year, and the $19,500 Hillman Hornet (see Helicom Commuter), which appeared last June.

Both of these helicopter kits make excellent projects. The Scorpion is a bit smaller and lighter, and features a specific-to-the-aircraft engine which, like the helicopter, is a product of RotorWay, Inc.

The RotorWay program is a remarkably complete one, and includes not only the helicopter kit purse but courses and seminars in construction of the kit and flying the completed helicopter; RotorWay even operates a flight school with a fleet of 8 Scorpions in which homebuilders are taught to fly their creations.

The Hillman Hornet helicopter is a development of an older design, the Helicom Commuter; plans for the basic design are also still available from the designer, Harold Emigh of Palm Springs, California.

This aircraft, which is a bit larger than the Scorpion, uses a Lycoming 0-320 engine, and its transmission uses gears and shafts rather than the V-belts and roller chains of the Scorpion. In a way, it’s a somewhat more substantial aircraft—re-fleeted, of course, in the $6,000 price difference for the kits.

Both are designed to be assembled by someone with normal manual dexterity and standard home-workshop tools; for the price, they represent quite a deal — and you not only get the fun of flying them, but about a year of evenings and weekends building them.

Maintenance on the homebuilts is actually much cheaper than on commercial ships, since it can legally be done by the pilot. Once you have a helicopter, can you go wherever you want with it? Unfortunately, no—local zoning restrictions and similar rules don’t give you quite the freedom of the skies that you might like, especially for regularly-repeated operations.

It will be years before you’ll be able to ‘hop into the helicopter and fly down to the supermarket for a six-pack—even if you could ever afford to use a helicopter for that sort of trip. The era of a helicopter in every garage will probably never come — but at least there are both reasons and ways to have helicopters in more garages than ever before.

Coming home from the office is easy if you’re attorney F. Lee Bailey. Just ease your trusty Enstrom down on your private landing pad . . . push a button to open the garage door and align the chopper in the right direction . . . and trundle it into the garage.

Be the first to comment on "A Helicopter In Every Garage"