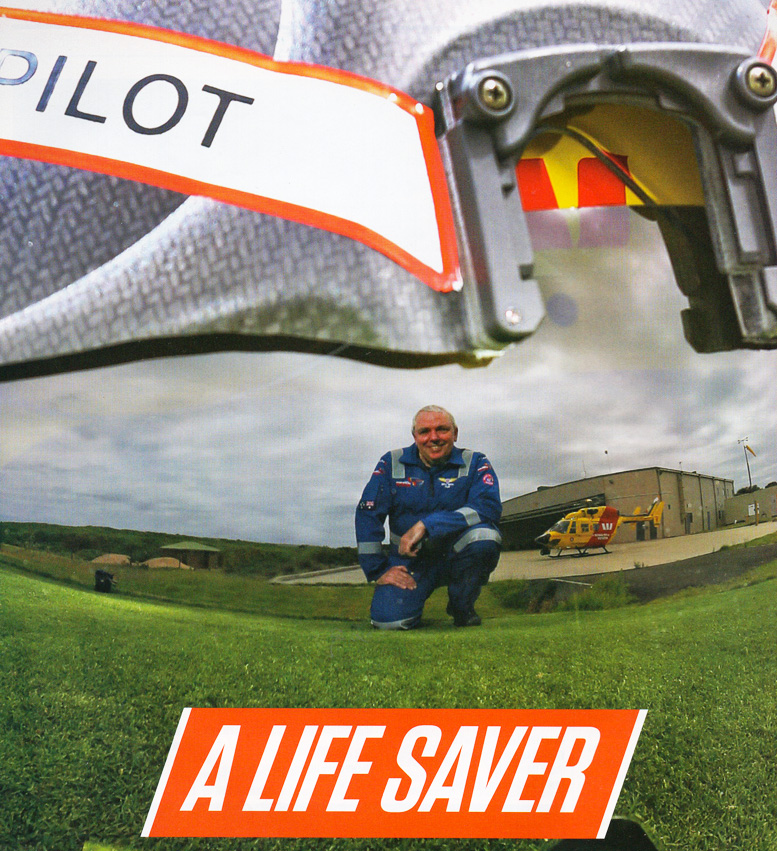

A glut of low-timed commercial pilots all vying for a seat in the cockpit of a commercial airline steered the career of Peter Yates, now chief pilot of the Sydney and the NSW South Coast Westpac Life Saver Helicopter Rescue Service, into the world of rotary-wing aviation and saving lives for a living, via Papua New Guinea

COURTESY: Australian Aviation January/February 2016

With around 6,500 hours in his logbook, and ratings on 11 helicopter types, including some time in the Russian-built Mil Mi-17, Yates spent 11 years flying in PNG early in his career with this experience proving to be the foundation for a career in emergency medical service (EMS) and search and rescue (SAR) operations.

Growing up as a five-year-old in the northern Sydney suburb of Lindfield, Yates, 54, said his interest in aviation began while lying in the backyard looking up at the sign writing aircraft flying above. “I also remember having Airfix models. My father smoked cigars, so he used to make clouds for me to fly them through.”

Starting school, his interest in aviation was put on hold until after finishing his studies. Working for a company that sold automotive electronic tuning equipment in the service department doing repairs, and having been bitten by the travel bug, a visit to a newsagent to flip through a few travel magazines reignited his interest in aviation.

“I was looking through a magazine on northern Queensland and there was an article on the guy who started Air Whitsunday. He was an accountant and he got his pilot’s license and started an airline. Right there I thought ‘that’s me, that’s what I’m going to do’.”

On the way up

In 1983, Yates began his flight training on Cessna 152s and Piper PA-32s from Bankstown Airport and attained his then unrestricted private pilot’s license with almost 76 hours logged.

“I was always going to become a commercial pilot, but I got disillusioned by the fixed-wing industry as the airlines were not taking anyone on. The flying schools were full of commercial pilots working as instructors. You just couldn’t get a job. So I decided then to have a look at helicopters.”

Having never been up close to a helicopter before, let alone flown in one, Yates had his first helicopter flight in a Robinson R22 at Heliflite’s then Castle Hill facility in north-western Sydney.

The flight was also his first lesson on the road to a commercial helicopter pilot’s license. Yates had been talked into making superannuation contributions when he left high school, which he says was a very good piece of advice.

“Back in those days superannuation was not compulsory and you could cash in your super. So, I cashed it in to pay for my flying.” Completing his commercial pilot’s helicopter license in 1984, Yates began to look for ways to increase his hours and experience. Thankfully, the owner of Heliflite had offered him some part- time work doing joy flights.

“I would drive from Lindfield out to Castle Hill and do a five-minute joy flight to be paid a dollar. I was driving an old Toyota Land Cruiser and it was costing a fortune in fuel, but it was the only way I could build up hours.”

“Fortunately, I was in it for the hours at that stage and not so much the dollars. Although, after the flight you would be asked to do the banking and to wash some of the helicopters – you were a slave. As a 60-hour helicopter pilot there wasn’t much I would say no to doing. You had to rely on these guys to give you some flying.”

Over time, the joy flight work dried up and in 1989 he moved on to National Helicopters where he got even less work.

“But it was there when I saw an advertisement in the paper for a company called Pacific Helicopters for long-lining work up in PNG. I didn’t have the minimum requirements for what they were wanting, but I put in an application anyway.”

“I was invited up to Brisbane for an interview – they interviewed about 60 people. They said ‘you don’t have enough hours to fly Hughes 500s, but do you want to work as a copilot on a Puma?’ To which my response was ‘yes’.”

Watch out for the falling coconuts

Flying above the PNG highland – Peter Yates’s career was kick-started flying Hughes 500s in PNG

Now flying in the highlands of PNG, Yates gained his Bell 206 JetRanger endorsement and some time flying a long-line to get familiar with the work he would be doing and completed two weeks of ground school on the Puma.

“The long-lining was to build and service oil rigs in the dense jungles. It was flat out going out and back to the rigs all day. The Pumas were working about 10 hours a day so they had a morning crew and an afternoon crew.”

“We were on a three-week rotation out of Australia and the maximum we could do was 110 hours in those three weeks and we would always max out on hours.”

Though living rough when it came to accommodation, which has certainly put him off camping for good, the opportunity to be sitting next to experienced pilots taught Yates invaluable lessons about PNG’s weather and the best way to navigate through the mountainous terrain. Yates then gained his Hughes 500 endorsement which saw him flying out to rig sites using dead reckoning navigation.

“In the middle of the bush, you would fly a surveyor out to where they wanted the rig to be and throw a roll of toilet paper in the trees below to mark its position. You would later return with a guy and a chainsaw to literally drop him in to start lopping trees to make a helipad big enough for a 500. Then you would start bringing in more equipment and people until it slowly built up into a full-sized oil rig.”

“Finding a rig in its early stages of construction among the dense trees was sometimes challenging. If I was flying people out I would say to them ‘let’s see who spots the rig first’, so I had everyone keeping an eye out to help me find it.”

While the flying hours were building up in his logbook, the tour of PNG was quite a cultural experience as well. Besides long-lining, Yates would be tasked to do medevac flights transporting villagers out to hospital.

“We would also fly coffins, which would be tied down cross-ways in the back of the 500 with the doors off and either end hanging out in the breeze. It was a real status symbol for them to have their coffin flown back to the village in a helicopter.”

“But you had to be careful, if you were the one who flew them to hospital, and they died, the locals would hold you responsible. Often a different helicopter company would fly the coffin back, just to be safe.”

Adding to his R22, Bell 212, JetRanger/LongRanger, Hughes 300/500, Lama, and Puma endorsements, Yates also flew the heavy lift Mil Mi-17 and Kamov Ka-32 on long-line jobs while in PNG.

“They flew me to the Mil factory in Moscow for a month to do my Mi-17 endorsement. We had some spare time and asked if I could fly the Mi-24 Hind. It was a famous Hind called ‘Red 11’ which was first shown to the western world at Farnborough the year before.”

“It had no weapons on it, but we did practice some strafing runs on a couple of people having a picnic on the edge of the Moscow River, all done at 300ft and below. The Hind has the same running gear as the Mi-17, just with a different fuselage.”

Yates explains that the art of flying precisely with a load slung 100ft below took a while to perfect. “To start with they would give you the empty loads, which were actually harder as there was no weight to them.”

“Once you got that worked out, they would give you loads to fly out but the pilot next to you would take over before you got to the landing spot. It’s like landing but you’re 100ft above the landing spot. It’s quite hard on your back as you spent a lot of time twisted, leaning out the right door and looking down at the load.”

In its heyday, Pacific Helicopters had around 100 pilots. Through attrition, Yates became a senior IFR pilot. However, a change of chief pilot who was critical of Yates having too high a standard, rang alarm bells. “That’s when I decided it was time to leave PNG and return permanently to Australia.”

Saving lives for a living

In early 2000 Yates took up a position at the now defunct Telstra Child Flight in Sydney, the dedicated neonatal and paediatric helicopter retrieval service that flew sick and injured babies and children to specialist hospital care.

Becoming endorsed on the BK117, Yates enjoyed the fact that he was helping families in need and was making a difference. But he admits it was difficult at first.

“I didn’t have any background in seeing or dealing with parents who were very stressed out, who had just given birth to a kid about the size of your hand. But once I became accustomed to that it was a good introduction to EMS work and getting experience of being around hospitals, sick people and doctors.”

In PNG, Yates says if the weather was really poor the decision not to fly was made quite easily, but when a life was in the balance, that decision was not as easy. “The decision to say that you couldn’t go when you’re dealing with life, you felt that little bit of extra pressure. It’s got to be safety first. The pressure is turning around to say no, if you have to.

“In PNG sitting back as an experienced pilot, you would see the dynamics, which you didn’t see when you first got there. There would be five pilots sitting in a room and the client would come in and say ‘I need someone to fly over to there’. It would go around the room with the most experienced guy saying no, due to weather.”

“It would end up with the least experienced guy doing it because they felt if they didn’t do it they would loose their job. Having spent 11 years going through that process it gave me a really good backing for EMS and SAR for when I needed to say no to doing a job. From the people who were tasking you it was ‘what do you mean you’re not going?’ But you can understand that because they are not aviators.”

Flying between the flags

Yates started at the Westpac Life Saver Helicopter Rescue Service in December 2000 to fly the iconic red and yellow ‘surf rescue’ helicopter above Sydney’s beaches. Although he initially did not have a winch endorsement, he did have around 1,700 hours of long-line experience, leaving him well placed to describe winching in the hover from a pilot’s perspective.

“Winching over water is certainly the hardest place to hover. Over land with a tree as your reference point, if it gets bigger, you’re moving closer, if it moves left, you’re going right. But over water everything is moving.”

“What we do is start winching the rescue crewman down the wire as we’re approaching the patient in the water to minimize the time in the hover. You lose sight of them for just a few seconds but as soon as they’re out of the water it doesn’t matter if you move a little left or right.”

In January 2003 Yates became Life Saver’s chief pilot, the position he holds today.

“When I was in PNG everyone would ask ‘what do you want to do?’ and I always said EMS. Rescue has more variety and it’s more ‘PNG’ where you go and land in small areas and where you have to think on the move. Getting into EMS and SAR involved some luck. I could have spent 10 years trying to get in to rescue, but I was in the right place at the right time.”

Heading up the flying side of a Sydney icon for the past 13 years, a service that is now into its 42nd year of operations, is a real privilege for Yates, although there is more to it than just flying.

“We have two distinctive liveries on the helicopter – the red and yellow, representing Surf Life Saving Australia, and the ‘W’ for our major sponsor, Westpac. Apart from the responsibility of ensuring safe operation and mitigating risk when we fly, as chief pilot, you also have to be very mindful of the client and the sponsor.”

“If you do a winch these days there will be 50 people at the top of the cliff with their mobile phones filming. What people don’t see until they get into this type of organization is the risks on the corporate side.”

Looking back over the hundreds of jobs Yates has flown at Westpac Life Saver and equally the amount of lives he has helped to save, there is no one mission that is a clear standout, rather a combination of a few that have defined him.

“Not all jobs are life and death, but there have been some jobs where that person was dead had we not been there. When those jobs do come along they make you want to come back, well, at least for another year.” Yates describes one job where the helicopter he was flying did make a difference.”

“A couple had been enjoying an evening champagne together while admiring the view on the coast at Waverley Cemetery. The guy had fallen down to the rocks some 50ft below. We threw the searchlight on him and from where we were sitting he looked dead – he was white as a ghost. The consensus with the other services on scene was that he was pretty much dead. The waves were crashing in on him. He was really smashed up.”

“While we weren’t in the business of doing body recoveries, we winched down our medical crew to check him. The bottle of champagne they both had been drinking was still standing proud at the top of the cliff and I used it as my hover reference for the winch.”

“The paramedic spent most of the time holding the patient’s head above water until the doctor could get a strop around him for the winch up. We got him to the nearby bowling green and transferred him with our doctor to an ambulance, as we had to go back and get the paramedic who was still on the rocks waiting for us.”

“Several years later the guy walked into the base to thank us for what we had done. Unfortunately, I wasn’t on shift that day to meet him, but the events that night changed his whole life. He had been a bit of an alcoholic and a no-hoper. Since then he had turned his whole life around.”

With Yates’ wife also in the aviation industry as an air traffic controller, conversations around the table at night can quickly turn to aviation.

“Over the years we have occasionally exchanged a brief greeting to one and other over the radio. On the way to an inter-hospital transfer job to Lithgow, I was airborne from the base and could hear her voice on the radio.”

“She sounded quite busy. Eventually I got hold of her and she said ‘I bet I know where you’re going’. What I didn’t know was at that point she had just received a MAYDAY call from an aircraft that had crashed east of Lithgow.”

“As we were talking, the message was coming into the helicopter from our tasking agent diverting us to this crash. It was an unusual situation. I don’t know how many times in the world this has happened, where she’s taking the MAYDAY call and I’m off to rescue them.”

Be kind to your mother From R22 joy flights over Sydney, to long-lining in PNG and to saving lives across NSW, what advice would Yates offer for an aspiring commercial helicopter pilot?

“PNG – it’s a good area to learn, but you are not going to get there unless you get some experience. I learnt a lot there which really helped me through my whole career, like decision-making processes as everything you did was so vital, the wrong decision meant you could kill yourself quite quickly – and people did.”

“But the best thing for a new commercial pilot I think is to try and get a copilot’s job flying in the offshore sector. You will get glass cockpit experience, you will get turbine and twin-engine endorsements and you will get multi-crew experience. If you go into other areas of the industry you are not going to get all of that.”

Yates notes the workload for getting a single-pilot command instrument rating can be very high and advises those wanting IFR experience to go offshore.

“Going into the offshore environment you work two-pilot IFR and you get to polish your instrument skills in a safer environment. For some people IFR is not for them, and then you’d be looking at doing fire work or VFR charters.”

“With EMS and SAR, it has pretty much become the domain of the military. By becoming a military pilot you will leave the service with IFR, with a twin rating and NVIS (night vision imaging system) – which alone is an expensive add-on for anyone.”

“The military ticks a lot of costly boxes. If you want a ‘free’ ticket, go military, but keep in mind that you have got to be prepared to go to war.”

A keen snow skier, amateur nature photographer and motorbike rider, questioned on whether his current role was a dream job, Yates was quick to respond “yes”. Although as chief pilot, he didn’t fly many hours in the last year.

“I’m so embedded these days in paperwork and CASA regulation changes that I don’t know if it’s as enjoyable as when I was just flying as a line pilot. For me, doing EMS and SAR I have the chance to give back to the community and I’m really enjoying that. It’s what keeps me motivated to keep coming to work … even through all that Sydney traffic.”

Despite the uncertainties and frustrations in the industry of the pending regulatory changes, Yates is optimistic the industry will ride it out and see its way through, and encourages future pilots not to be deterred.

“I think the industry needed a revamp probably 20 years ago, but it didn’t happen. Some of the changes we’re going through now probably should have happened over time. The problem is because they haven’t, there is a lot of change happening in a short time.”

“CASA is also changing its thought processes and following the EASA and the ICAO lines a lot stronger. So we are I in that difficult position of no-one likes change and we are just about to cop a lot of it. I think for the pilots starting in the next five years it will just be ‘the industry’ again.”

Be the first to comment on "A Pilot – A Life Saver"