Reading The Weather Up There

Clouds are messages that tell pilots what’s going on with the weather. As Philip Smart explains, the safe conduct of a flight can rely on a pilot’s ability to interpret those messages correctly.

COURTESY: Australian Flying March-April 2018

EDITOR: As a youngster, I surfed most of Australia and different places around the world. I spent my first few years as a Life Saver at Ocean Grove family beach. This was an invaluable experience…why you ask? – and what does this have to do with Aviation Weather? Well, the one essential tool of the sport is the ability to

I had a very high success rate with finding the best waves and being in the right place to catch them. So what does this have to do with flying? Reading the weather allows you to plan, avoid and enjoy every flying situation you encounter. Knowledge is power, and knowledge is SAFETY!

An Australian Perspective

One of the myriad ironies of flying is that handling the weather can be a private pilots greatest source of both frustration and satisfaction in a single flight.

General aviation aircraft have to share the sky with clouds, so knowing what the various types mean can be key to a safe flight.

For weather-seasoned pilots there can be a sense of satisfaction when the wheels kiss the tarmac at a destination, having planned well to side-step that storm front, picked their way through annoying but manageable weather and even hitched a tailwind ride from weather that was going their way.

There is also an appreciation that the only way to accomplish an intended journey from one part of the world to another today will depend on understanding of how that natural world works, of becoming part of that environment rather than a casual observer.

For many this realization of aviation weather is just part of the puzzle that makes flying a way of life, not just a hobby.

Cloudy ahead

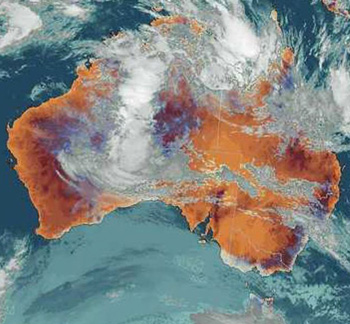

The sheer size of cloud formations can be seen in this Bureau of Meteorology satellite image. IMAGE: BUREAU OF METEOROLOGY.

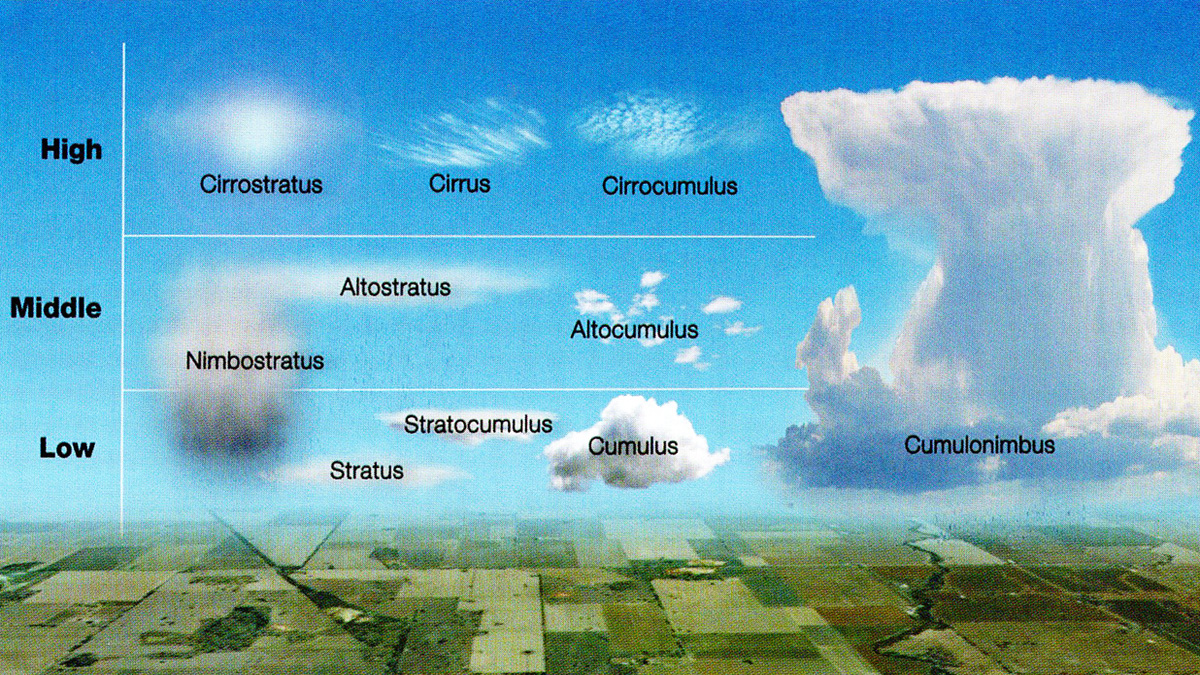

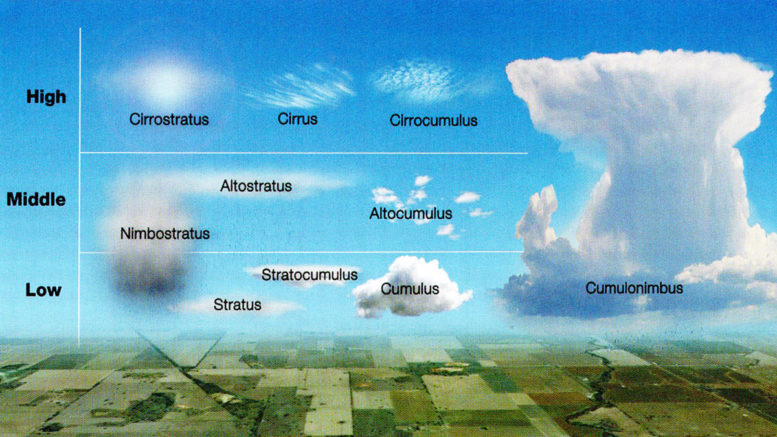

In 1803 London amateur meteorologist Luke Howard proposed a system of categorizing clouds that has become standard today.

His “Essay on the Modification of Clouds”, (in the scientific community “modification” could also mean “classification”) wasn’t the first attempt at providing a standard nomenclature for cloud formations, but as the first to use the universal language of Latin it gained more widespread acceptance than previous systems based solely in French or English.

It is from Howard and his understanding of Latin that we gain the major cloud categories of Cumulus, from the Latin “cumulo”, meaning heap or pile, Stratus, from the Latin prefix “strato”, or layer and Cirrus, Latin for “lock of hair”.

He also identified a series of intermediate and compound modifications, such as cirrostratus and cirrocumulus and wrote on the importance of clouds as visual signposts illustrating the state of the atmosphere and offering clues as to what might happen next.

“Clouds are subject to certain distinct modifications, produced by the general causes which affect all the variations of the atmosphere; they are commonly as good visible indicators of the operation of these causes, as is the countenance of the state of a person’s mind or body,” Howard wrote.

Today Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology recognizes 10 main clouds types, further subdivided in to 27 sub-types according to their height shape, color and associated weather. And a few more Latin terms have joined the lexicon.

A cloud producing rain will include the term “nimbus” in its name, while fragmenting clouds may carry the “fractus” suffix. Clouds are formed from evaporation of water from the earth’s oceans, lakes and rivers and transpiration from plant life.

As this moist air rises it reaches altitudes where the air pressure is lower, so it expands and cools. As air cools its ability to hold water vapor decreases, so the air becomes saturated and some of the water vapor condenses in to water droplets, forming clouds.

Steady On

The type of clouds visible point to the stability in the air around them. Moist unstable air will continue rising, forming cumulus clouds with tops that continue climbing. This type of cloud is usually associated with turbulence, sometimes with short, sharp rain showers but good visibility between the showers.

Pilots operating in Australia’s tropical north are familiar with these aviation weather conditions, with one telling Australian Flying that his Bombardier Dash-8 couldn’t climb as fast as the afternoon cloud tops out of Darwin.

This can also be good weather for glider pilots, as rising columns of air that remain warmer than their surroundings will continue to rise, creating thermals. A rising parcel of air that achieves the same temperature as the ambient air around it will stop rising and become part of a more stable atmosphere.

Stratiform or layered clouds are more likely to he formed in this instance. With more stable air rain will be more steady, with generally smoother air and less turbulence, but also the potential for fog. While cloud formation is generally caused by a body of air rising, the reasons for its movement can vary.

Aviation Weather: Convection

Convection is when a layer of cooler air is moving or laying over a warmer layer beneath, warmed perhaps by reflected heat from the earth’s surface or even air pollution from a city.

The warming effect from the lower layer will cause the upper layer to rise, creating turbulent air. Convection can produce some unusual effects for pilots, with two essentially separate weather patterns sitting on top of each other.

Helicopter pilots transiting from Esso’s Bass Strait oil platforms to their base at Longford in Victoria have reported occasional conditions where flights out and back at different altitudes can have a tailwind in both directions.

Aviation Weather: Orographic lifting

A moving air mass will rise as it meets a mountain or ridge, with the increase in altitude producing a decrease in air pressure that may form clouds.

The air mass may continue over the land mass and descend on the other side to increasing air pressure, with the clouds dissipating. With air rising to lower air pressures on the windward side of the land mass, that is often where clouds will begin developing.

Orographic lifting can result in cloud forming and sitting over the top of the land mass, even though the airflow is continuing through it. This phenomenon is often seen in the Pacific Ocean, where navigators since the days of Captain Cook have often identified the presence of islands by the cloud sitting over them.

It can also be the cause of regular cloud formations that become part of a regions normal weather patterns. Pilots flying to the east of the Great Dividing Range can expect cloud there whenever there is a westerly wind blowing.

Aviation Weather: Turbulence and mixing

Eddies from local land masses, ground temperature variations and local winds can all affect an air mass as it moves across the ground, creating turbulence that can mix air, change its temperature and force it to rise to a higher altitude, with the potential to form clouds.

While glider pilots look for fields of different colors, knowing that where light meets dark there will be a temperature change that may create an updraft thermal, powered pilots often try to avoid these situations and the bumpy flight that may ensue from turbulence.

Man-made temperature factors such as massed industrial factories can also enter the equation. The heat from burning cane fields in Queensland has sometimes been credited with triggering local thunderstorms by introducing a large mass of hot, rising air in to an already unstable tropical weather system.

Aviation Weather: Widespread ascent

Widespread ascent is often characterized by weather fronts, as two adjacent air masses meet and slide over one another. Although the boundary between the masses is called a front, it is rarely a vertical wall.

A cooler air mass such as a southerly change from the ocean in southern Australia will begin to drive a wedge of cooler air under a warmer air mass sitting over land, gently (and sometimes not so gently) forcing the warmer air mass to rise.

In some parts of Australia this meeting of land masses can generate rising air of considerable strength. A glider pilot from the coastal city of Whyalla in South Australia told Australian Flying of being airborne in a single seat glider during the approach of a front, with nose pointed vertically at the ground and speed brakes out and still hearing the variometer buzzing with a positive rate of climb.

Aviation Weather: Convergence

When large masses of moving air meet, the result is not necessarily a front. The Doldrums, an area near the equator where the northeast and southeast trade winds converge, is famous among sailors for its long periods of slack winds in a trough of low pressure.

But convergence of surface winds with winds at even 2000 feet altitude can cause lifting. With sufficient moisture in the air, this may create widespread cloud cover along the line of the trough.

Ten main types of cloud

LEFT TO RIGHT: 1. Altostratus often deposits

good quality rain. 2. Something’s building over the range. What do the different cloud types here tell you about the conditions you’re about to fly into? 3. Bushfires can cause an unexpected build-up of cumulonimbus clouds, which is commonly referred to as pyro-cu.

Low Cloud

Low cloud is generally cloud with a base from near the earths surface to around 6500 feet in middle latitudes. Low clouds by nature are generally in warmer air, so they are almost entirely water, but in some conditions can be at sub freezing temperatures and contain snow and ice.

-

Stratus is often seen as a cloud layer with a uniform base, found in the low levels of the atmosphere. Precipitation from stratus cloud is likely to be a light drizzle.

-

Stratocumulus can be a sheet or patch of cloud, sometimes formed on the break up of a stratus. Stratocumulus can indicate some turbulence and possible icing at subfreezing temperatures. It can appear grey, white or both. As a patchy cloud, visibility can be better than with a later of stratus.

-

Cumulus clouds are generally detached and dense. These are the towering “cotton wool” clouds with sometimes brilliant white tops, while the bottoms may be dark as their thickness prevents sunlight penetrating to the base. Cumulus can produce intense, short rain, the kind that soaks a small area while leaving areas either side dry.

-

Cumulonimbus is the largest cloud form, often forming at lower altitudes but extending to high altitude. It is the heavy, dense, towering dark cloud that can sometimes spread out to be the classic “anvil” a warning of highly turbulent air that should be avoided and a precursor to thunder and lightning.

-

Nimbostratus: as its “nimbus” connection suggests, this is a stratus cloud that will produce rain, often continuous but moderate. They generally form through from an altostratus becoming taller and deeper, with the ability to hold more moisture. This often brings the cloud base lower, with the cloud producing heavier rainfall and appearing darker in colour.

Middle Clouds

Middle clouds are those with bases from around 6500 feet to around 23,000 feet. They are still primarily water, some of it super cooled.

-

Altostratus is often a bluish veil or cloud found at middle altitudes. Altostratus is one of the clouds most known for good rain across large areas of Australia. Sunlight is often dimly visible through Altostratus, which is generally indicative of a stable air system with little or no turbulence and moderate amounts of ice.

-

Altocumulus appears as white or grey patches of solid cloud, resembling waves or rolls. Altocumulus can create some turbulence and small amounts of icing and light rain showers.

High Cloud

-

As high level clouds, these are often at altitudes where freezing temperatures mean any moisture is held as ice crystals rather than droplets. High clouds generally have bases at altitudes between 16,000 feet and 45,000 feet.

-

Cirrocumulus clouds are generally smaller higher level clouds with a rippled appearance, that don’t produce precipitation. They are often thing, appearing to be made up of flakes or patches. They may contain supercooled water droplets. For pilots, they can generate some turbulence and some icing.

-

Cirrostratus is the cloud associated with a halo or luminous circle around the sun or moon as its ice crystals refract light. White and wispy, it can often appear as a sheet of cloud. Although the cirrostratus has little if any icing, its halo effect can restrict clear visibility.

-

Cirrus appears at altitude as delicate white strands or filaments, or narrow bands. Cirrus is composed of ice crystals cirrus moving quickly through the atmosphere and does not produce precipitation.

Thunderstorms – the Darth Vader of airborne weather

After more than a century of powered flight, thunderstorms remain the single most dangerous aviation weather phenomena for small and large aircraft alike.

Accident reports are littered with examples of aircraft destroyed when the air movements inside a storm created stresses that exceeded the aircraft’s structural limits, often resulting in in-flight break up.

“Thunderstorms remain the single most dangerous weather phenomena for small and large aircraft alike.”

Darth Vader? A tropical thunderstorm rolls over the Gold Coast.

Thunderstorms are created in a deeply unstable atmosphere with high levels of moisture, triggered by the presence of something that forces a great volume of air to begin rising, such as a fast moving cold front or strong local heating of air in contact with the earths surface.

The rising air acts like a self-generating storm, as moist air condenses in to liquid droplets, giving off heat which further heats the surrounding air to continue its drive upward.

The pressure difference can then draw in air from the base of the cloud, continuing the process. A building thunderstorm can contain updrafts rising at up to 5000 feet per minute, with the cloud going to as high as 55,000 feet in the tropics.

At higher altitudes moisture freezes to become ice, which then falls through the cloud, dragging air behind it in the form of potent downdrafts. This is where rain may begin to fall from the base of the cloud, indicating the storm is at its strongest.

A fully fledged thunderstorm threatens aircraft in the vicinity with a multitude of dangers, from updrafts capable of overloading its structure, to severe turbulence, wind shear of 50 knots or more, hailstones, severe icing, poor visibility and lightning.

Electrical interference can compromise radio communication, navigation equipment use or damage to systems, while intense visual cues and turbulence can disorientate pilots.

These effects are of sufficient magnitude that aircraft of any size can be damaged, leading to the famous sign reputed to have hung above an operations building door at Davis Monthan air base in the United States in the 1970s, which stated “There is no reason to fly through a thunderstorm in peace time”.

Knowledge is your friend

As with all aspects of flying, knowledge and understanding of aviation weather and cloud formations, their immediate effects and the cues they give for how weather may evolve, can help pilots plan safe, enjoyable flights for themselves and their passengers.

In many cases understanding en route aviation weather provides the satisfying challenge of reaching the destination safely after negotiating weather that had the potential to cause issues. But it can also serve the very important purpose of convincing a pilot that today’s flight is simply best abandoned in the name of safety.

Summary Article NameAviation Weather - Reading The SkyDescriptionAviation Weather is a science, but not a difficult one. Learning how to read the weather can help make your time in the air more enjoyable, but get it wrong and you'd better start remembering your emergency procedures, just in case!AuthorPhillip SmartPublisher NameAustralian FlyingPublisher Logo

Article NameAviation Weather - Reading The SkyDescriptionAviation Weather is a science, but not a difficult one. Learning how to read the weather can help make your time in the air more enjoyable, but get it wrong and you'd better start remembering your emergency procedures, just in case!AuthorPhillip SmartPublisher NameAustralian FlyingPublisher Logo

-

Be the first to comment on "Aviation Weather – Reading The Sky"