COURTESY: Kitpalnes Magazine February 1998.

Bird’s BabyBelle: A first-time builder’s Canadian Home Rotors kit helicopter wins the Oshkosh Grand Champion rotor craft award.

It looks like a 1940s American Bell 47, but this helicopter is actually a Baby Belle, built from a kit by Canadian Home Rotors (CHR) at Ear Falls, Ontario. Murray Sweet and Doug Fulford, president and vice president respectively, formed the company in 1986 and began kit deliveries in 1991.

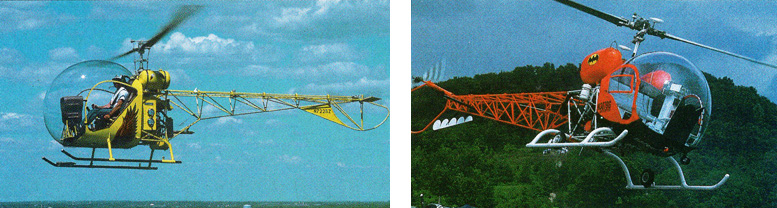

Here’s a profile-view comparison between the Baby Belle (left) and a genuine Bell 47G.

Baby Belle is built much like the helicopter it replicates; it employs a welded chromoly airframe using two-blade main and tailrotors and an engine installed vertically. Both the Baby Belle and early Bell 47s are two seaters, but the CHR kit version has a 25-foot main rotor diameter compared to the Bell’s 35-foot rotor.

The big Bell was powered by a 178-200-hp Franklin (later a 200-hp Lycoming), and the Baby has a 160-hp Lycoming 0-320. The prototype Baby Belle now has more than 1000 flight hours. Mark Richards, company chief pilot said, “Initially we had growing problems, but for the past some 630 hours, the helicopter has been trouble free.”

Richards has flown the rotary-wing craft from Ear Falls to Sun ‘n Fun in Lakeland, Florida, several times—the 1900-mile trip taking six days and 25 en route stops.

Baby Boom

Several hundred partial kits have been delivered to customers in Canada, the U.S. and abroad, along with 24 complete kits. Countries include Brazil, Peoples Republic of China, Italy, Sweden and South Africa. Six to eight Belles are flying, including examples in Italy and China.

The Bird Belle

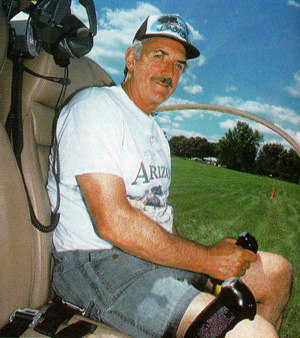

Baby Belle builder Leroy Bird assumes the pilot position in his award-winning helicopter. He is working on a helicopter license.

One Baby Belle Helicopter customer is 57-year-old Leroy Bird of Paw Paw, Michigan, who retired last summer as president and CEO of Cash Register Sales & Service in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He obtained a quick-build kit in April, 1996, and started work on it in September, ’96, with the assistance of Mike Westveer, an A&P mechanic.

“I wanted to be sure that I was headed in the right direction,” Bird said. He was. The FAA issued a certificate of airworthiness on July 15, 1997, and Bird’s .Baby Belle flew for the first time a week later. Doug Fulford made the first flight and most of the subsequent FAA-required test hours.

The first flight lasted 20 minutes and only one adjustment was required after landing: to turn the cyclic (pitch) control rod 1.5 turns. No other modification was necessary in the next 30 hours. Unique in this situation is that Bird has neither a fixed- nor rotary wing license.

He was an electronic countermeasures operator on a Navy P2 during the Vietnam era and was a student pilot, but he never went beyond soloing. “Now,” Bird said, “I have the time and resources to do what I have been thinking about for 10 years — the last five of which was to build and fly my own helicopter.”

I looked at all the two-seat homebuilts that appeared at Oshkosh for many years, but it was the Baby Belle Helicopter that I found most favorable.

“It has a certified aircraft engine, a heavy geared transmission, driveshafts rather than belts or chains, fantastic visibility, and safety engineered into it. A helicopter instructor friend and I went to the factory at Ear Falls, where I had a flight in a Baby Belle and then purchased a kit that included construction drawings Number 200.”

Bird rode the right seat a number of times when Richards flew the Bird helicopter, but at the time of this writing, Bird had only two official flight lessons logged. More flight time was expected soon with an instructor friend.

Building The Baby Belle Helicopter Kit

The construction site was rather unusual: a 20×37-foot work area established in a llama barn (Bird’s wife, Leah, raises llamas). Building was done in the evenings and on weekends—4.5 hours every night and 10-hour days or more on the weekends. “Sometimes I had to walk away and forget the helicopter,” Bird commented, “because the stress built up too much.”

Nevertheless, 1200 work hours later, the Baby Belle Helicopter was completed in time to take it to last summer’s Oshkosh convention. Bird’s quick-build kit came with a prewelded fuselage, but he had to weld on tabs to carry the cabin and enclosures, formed from 4×12-foot 1033 aluminum flat stock.

Bird also made the strobe light mounts, formed engine cooling shrouds, modified engine accessories, converted the Lycoming 0-320 from a horizontal to vertical installation and more. “Some airframe panels and parts were fabricated several times before I was satisfied with them,” Bird said.

Canadian Home Rotors V.P. Doug Fulford enjoys flying Leroy Bird’s kitbuilt Baby Belle at Oshkosh ’97, where it won Grand Champion rotorcraft honors.

Cabin doors were made and installed the night before a planned departure for Oshkosh, and upholstery was still being tacked in place as the helicopter was being trailered out of the barn by Bird, Leah, and Mark Richards. Bird notes that his helicopter follows the plans exactly, although he redesigned the instrument panel and installed a top-quality leather cabin interior.

Customized paint was also applied to the PPG yellow acrylic urethane finish in the form of an airbrushed and lacquered eagle in landing configuration on the underbelly of the Baby Belle Helicopter cabin. Bird credits the eagle application to Andre a Connor, an airbrush instructor from Allegan, Michigan.

He also cannot say enough about Canadian Home Rotor’s customer backup. “They even called me to ask if I had questions,” Bird declared. “My wife has likewise been very supportive from when I first started considering a helicopter 10 years ago to today,” he added.

Technical Details

Mainrotor blades are skinned all-aluminum structures with extruded aluminum leading and trailing edges. Blades are shaped by one solid rib each 6 inches from the root to 3 feet outboard, then one rib per 12 inches to the tip. Each blade contains 16 ribs. The mainrotor flies at 500 rpm, and tailrotor runs at a 5.4:1 rpm ratio.

LEFT: With dual fuel tanks and vertically mounted engine, the Baby Belle emulates its Bell 47G predecessor.

RIGHT: An uncluttered instrument pedestal has room for all the essentials.

The 4-foot – diameter, 4-inch – chord tailrotor blades are stainless steel, employing a solid stainless steel spar running out 6 inches from each blade root and wrapped with stainless sheeting to form the airfoil. A Delta teetering system provides the control.

Aluminum castings are used in the swashplate-controlled main rotor system, although the driveshaft is titanium. The driveshaft to the cast aluminum tailrotor gearbox and blade hubs is a 4130 tube. “We use actual Lycoming geared transmissions and drive – shafts to provide depend – ability and low maintenance,” Canadian Home Rotors’ President Murray Sweet explained.

The side-by-side two-seater cabin has an inside width of 46 inches. Dual controls are standard for the kit, with collective (vertical lift/descent) control sticks to the left of each person, and cyclic control sticks between legs as in other helicopters.

The instrument panel carries necessary operational instruments, but Bird has added a main transmission temperature indicator and chip detector light plus a tailrotor gearbox chip detector. A Narco 810 TSO com and AT 150 transponder are the only avionics.

Fuel capacity is 28 gallons, carried in two 14-gallon aluminum tanks aft of the cabin. The bubble is an actual Bell 47 series enclosure. Skid landing gear is built with 2-inch-diameter aluminum tubing. The bottom horizontals are black anodized.

Baby Belles have an overall length of 29 feet 8 inches with an empty weight of 920-945 pounds, depending upon equipment, and a 1450-pound maximum gross weight. Top level speed is 100 mph and cruise with two aboard is 80 mph.

With its immaculate leather appointments, the Baby Belle’s cockpit helped Oshkosh judges choose it as Grand Champion.

Normal climb is 1000 fpm at 45 mph; service ceiling is 10,000 feet; and maximum range tops 200 miles. Hover ceiling in ground effect (IGE) is 7000 feet, and out of ground effect (OGE) is approximately 2000 feet, the factory says.

The recommended 160-hp Lycoming 0-320-B2C sells new for $19,000 plus. Bird obtained his, a 270-hour engine from a Robinson R-22 helicopter, for $11,000.

The Baby Belle Helicopter kit cost was $38,000 in 1996, and the instrument panel setup and leather upholstery was an additional $3500. And what value does Leroy Bird place on his Screaming Eagle (a name given to the helicopter by Oshkosh onlookers)?

“At least $100,000,” Bird said. Sweet also noted, “Sixty percent of our business is flight-ready aircraft, at $91,000, for overseas delivery. Otherwise, a complete kit less engine is now $41,000, and we have some 233 builders.”

Baby Belle Helicopter – What’s Next?

Bird’s property in Michigan covers 40 acres, so he has a home heliport, plus a hangar—formerly a barn. Next on Bird’s agenda is to qualify for a student helicopter pilot’s license and build time with his Screaming Eagle. Then on to earn a private rotorcraft-helicopter license.

Until then, and when he can’t fly to an aviation gathering, you’ll be seeing his Baby Belle arrive on a converted car carrier trailer. He is proud of his Baby Belle, and he should be. It was the Grand Champion rotorcraft at Oshkosh 1997. That’s not bad for its first appearance off Leroy Bird’s Paw Paw property.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, contact Canadian Home Rotors

Lycoming flies to new horizons

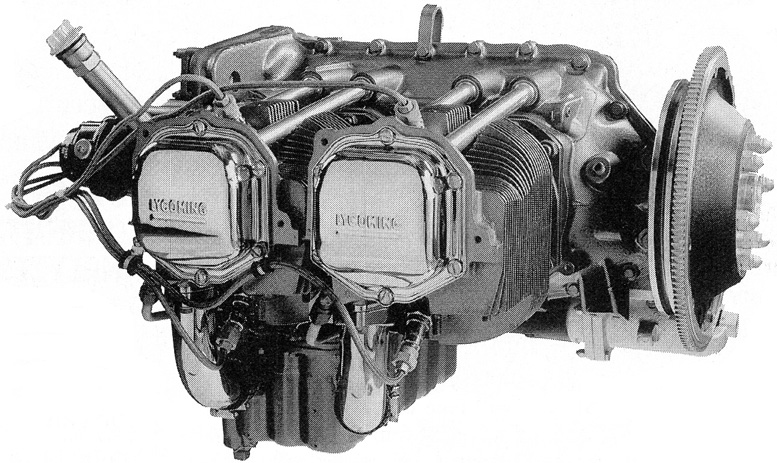

Thousands of 150-160-hp Lycoming 0-320-series engines like this are found in homebuilts including Van’s RVs, Stoddard-Hamilton Glasairs, Lancairs and Murphy Aircraft kits.

By John M. Larsen – February 1998

Sometimes it is easy to overlook the obvious!

Here at KITPLANES® we are constantly on the lookout for the latest—and hopefully the greatest—in new aircraft engine design. While this will always be our quest, we I need to acknowledge that as of February, 1998, the Number 1 homebuilder choice for engines over 100 hp is still Lycoming.

IFR Conditions

In the fall of 1997, the Lycoming plant in Pennsylvania was under siege by striking union workers. Managing Editor Keith Beveridge returned from an on-site visit to the factory where numerous pieces of equipment were up for auction.

Striking workers showed their discontent, both with their old contract and with the company’s trend toward the out-sourcing of parts and assemblies. One of the energy sources that keeps the rumor mill turning is the perception that Lycoming intends to have many of its engine parts built by companies outside the United States.

When interviewed, company spokesman Michael Wolf said that whatever new out-sourcing is done will be with U.S. companies, with the majority of these vendors located in the eastern United States. All Lycoming pistons have been made in Brazil for the past 25 years, so foreign out-sourcing is not new.

Customers with a new Lycoming on order need not worry because even during the strike, the company faithfully filled orders with the labor of salaried people and personnel with certified engine training.

On the Move

Lycoming has realized for some time that there is a big market in homebuilt aircraft. The company has gone after major kit manufacturers in a big way, evidenced by the fact that some prominent companies such as Stoddard-Hamilton (Glasair), Lancair, Van’s and Murphy offer new Lycoming engines at OEM (original equipment manufacturer) prices.

This means that if you buy a qualifying kit from one of these kit makers, you can get a new 0-320 for about $19,000. This is significant, as Lycoming dealers will ask for about $10,000 more for the same engine in a re-manufactured configuration.

In my area, the OEM price is only about $3000 more than the local engine-rebuilding shops wants for zero-timing your old engine. It also gives Lycoming’s competition something to consider when counting the cost of tooling up for their 160-180-hp offerings.

Getting Competitive

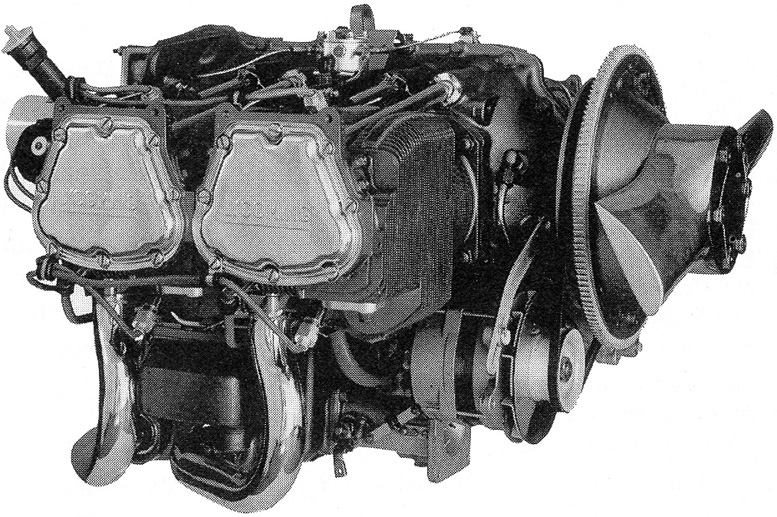

On its new models, Lycoming is offering the semi-automatic LASER ignition as an option. The system is made by Unison, the current manufacturer of Slick magnetos. Wolf said that Lycoming is taking a two-phase thrust at the future, with electronics being Phase 1. Specifically, Lycoming is working on implementing state-of-the art engine electronic controls.

The second phase is fuel management. The company has its eye on ultimate fuel economy by doing what it takes to give the pilot the most for his avgas dollar. The ultimate goal is to offer one-lever automatic piston engine control similar to that used on turbine engines.

This would give a big improvement to economy and performance. Cost is the barrier, so Lycoming is moving slowly to come up with the right package with price-conscious marketability along with the electronic benefits.

Why Do They Cost So Much?

The real driver of high aircraft engine cost is low volume. Lycoming makes many engine models—but only in quantities of a few hundred each. Total production was about 1200 engines for 1996 with 2000 projected for 1997 as Cessna reintroduces its single-engine C-172 and C-182.

By comparison, auto engine manufacturers turn out hundreds of thousands—even millions of engines over a period of years. When seen from the auto engine point of view, Lycoming resembles a custom-engine shop. That’s partly because much more attention to detail is required with the aircraft engine to ensure reliability.

This is a representative of the Lycoming 0-360 four-cylinder series.

Small aircraft engine production numbers also mean that at times the company has a problem getting reasonable prices from suppliers and vendors because of low-volume buying. Looking at the other end of the supply/demand curve, Wolf acknowledged that aircraft engine sales volume would increase with a large price reduction, and Lycoming would love to see it happen.

Yet a factor that cannot be overlooked is that cost-cutting often involves a reduction of jobs and is viewed as a hostile act by labor unions. There is also the issue of liability because juries and courts seem to hold aircraft-related incidents to a higher standard of accountability. All these things add up.

For the Future

By the time this column goes to press, the strike may be settled peacefully, and we all hope to see this American company going strong in America. The fact that Textron owns both Lycoming and Cessna means the engine maker will have a good customer for its powerplants.

Nonetheless, the company has a goal of seeing to it that the majority of homebuilt aircraft of the 21st century has a Lycoming under the cowl.

FOR MORE INFORMATION: Textron Lycoming

Can I schedule a tour of the “Baby Belle” factory at Mirabell Airport for this coming summer?

Please contact: https://www.safarihelicopter.com/