Dynamic Rollover Every Pilots Training

ARTICLE DATE: March 1990

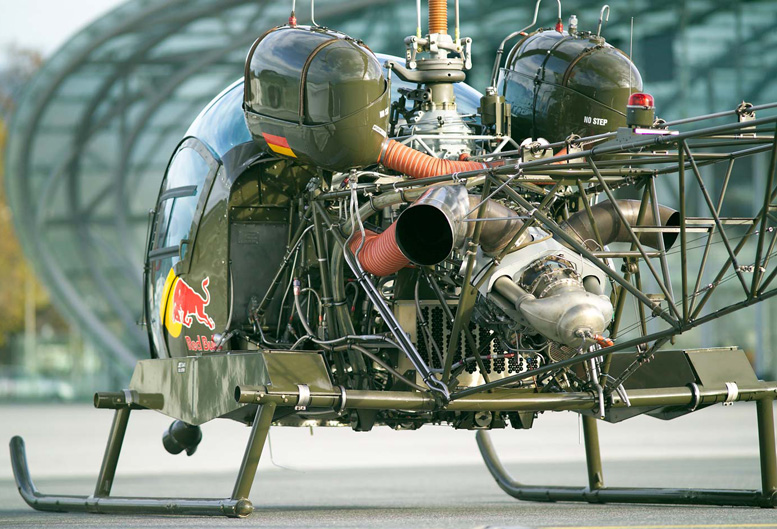

A BELL 47D HELICOPTER PILOT AND his friend moved the helicopter out of the hangar on a warm, late-winter day in southern Missouri. The mission: a short pleasure flight around the local area. The weather was perfect for the outing.

As the two maneuvered the Bell 47D helicopter on its ground handling wheels, the right wheel and skid slipped off the concrete helipad and got stuck in the mud. After much effort the pilot and his friend were unable to pull the Bell back onto the pad. The pilot told his friend to stand clear; he would fly the helicopter out.

That may sound reasonable to an airplane pilot who’s blasted the throttle to taxi through soft sod, but in a helicopter it’s a sure prescription for disaster because of a phenomenon peculiar to helicopters known as dynamic rollover. There are several possible takeoff and landing situations that can lead to dynamic rollover, but a stuck skid is the classic example.

Every helicopter pilot learns that during basic instruction. To understand dynamic rollover, you must understand that a helicopter pilot is flying the rotor disc, not the airframe, as one does in an airplane.

During normal maneuvering a rotor disc assumes many different angles relative to the fuselage. For example, in forward flight the rotor disc is tilted forward, pulling the helicopter along. In a turn the rotor disc banks into the turn and the fuselage follows.

When landing on a slope the rotor disc remains level relative to the horizon while the fuselage settles on its landing gear at an angle. But there are limits to the relationship between rotor disc angle and the fuselage that cannot be exceeded.

When one skid is stuck to the ground, the helicopter pivots laterally around it, banking toward the stuck skid, which acts as a fulcrum. The helicopter begins to rise, but let’s say the right skid is firmly planted.

The pilot senses the helicopter rolling to the right, so he moves the cyclic left, which levels the rotor disc parallel to the ground. But as the helicopter continues to rise the fuselage continues to roll right, toward the stuck skid, very slowly, and the pilot continues to move the cyclic left to counteract the roll.

At some point the pilot has the cyclic full left and the rotor disc can no longer be flown level with the ground. When that happens the rotor disc begins to roll with the fuselage and its thrust (instead of lifting straight up) is now a vector pointed right.

It’s over in a split second. The thrust of the tilted main rotor shoves the helicopter over on its side, and it thrashes to pieces. An eyewitness said the left skid of the Bell 47 lifted off the ground several times before the helicopter suddenly rolled over and caught fire.

The witness said a piece of one main rotor blade flew off just before the Bell 47D rolled over, but the NTSB blamed the accident on dynamic rollover caused by the pilot’s poor judgment in trying to take off with a stuck skid.

Dynamic rollover happens so quickly and from such an apparently small bank angle that the witness could have seen the rotor piece depart as the blades were striking the ground. It’s hard enough to understand how a helicopter pilot could be ignorant of dynamic rollover, but there’s more.

The Bell 47D helicopter was more than two and a half years out of annual, had been built from scavenged parts and had not complied with three airworthiness directives issued against it. Worse yet, the landing gear skids had been moved inboard about 11 inches on each side so that the helicopter would fit on a trailer.

There was no supplemental type certificate or any other authorization for the landing-gear modification. Such a cavalier attitude toward safety may also make a pilot believe he’s immune to dynamic rollover.

These articles are based on the National Transportation Safety Board’s reports of the accidents and are intended to bring the issues raised to the attention of our readers. They are not intended to judge or to reach any definitive conclusions about the ability or capacity of any person, living or dead, or any aircraft or accessory.

Be the first to comment on "Bell 47D Helicopter Accident"