BJ Schramm Rotorway Exec Helicopter Kit

B.J. SCHRAMM IS ON A ONE-MAN CRUSADE TO MAKE HIS HELICOPTERS AVAILABLE TO THE FLYING PUBLIC

ARTICLE DATE: August 1984

“Ultimately the only helicopter that will exist will be the personal helicopter,” said B. J. Schramm, conceiver, designer and manufacturer of the RotorWay homebuilt series of helicopters. He feels that the tilt rotor is the next generation rotorcraft and will eventually dominate the commercial world, leaving the conventional whirlybird solely for personal use.

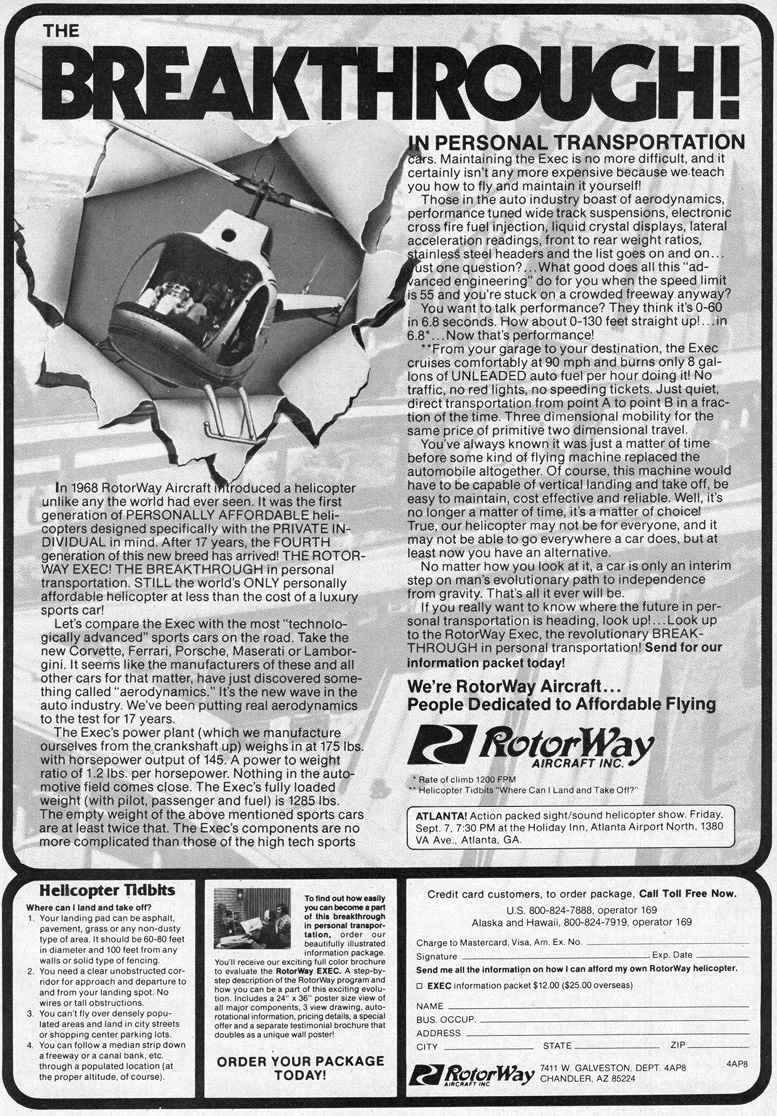

This was a strong prediction from a man driven to the task of bringing the world a personally affordable helicopter. And, in part, B. J. Schramm has indeed fulfilled his mission. The RotorWay Exec can be yours for a mere $26,000 . . . that is, of course, as long as you’re willing to spend the time to put it together yourself.

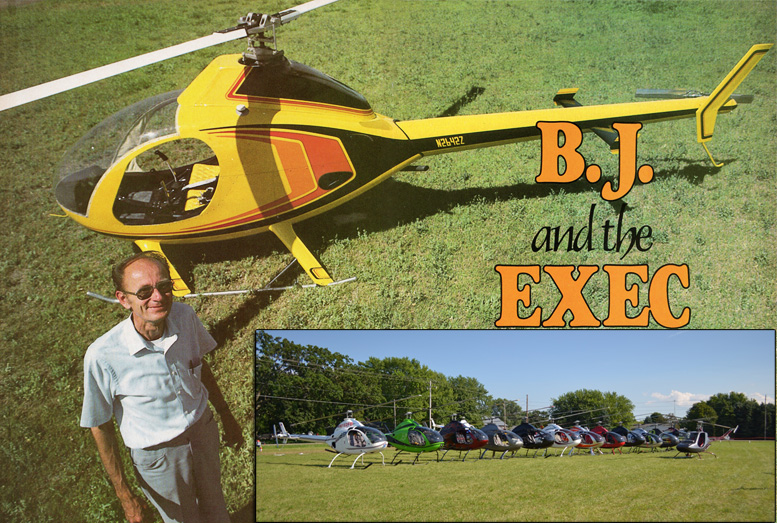

Sleek lines of the Exec are displayed at the RotorWay Arizona facility. This helicopter had the sleek and appealing looks from day one. Of course this didn’t hurt its aerodynamics with a notable high speed cruise.

The next closest entry in the private helicopter competition, however, is a factory-built machine which currently tips the scales near $80,000. In comparison, the RotorWay Exec helicopter is a dream, for many, come true.

Interestingly, Schramm claims that most of his homebuilders have had little prior experience in aviation, I underlining the fact that he isn’t selling to A&P mechanics but to average citizens with a yearning for whirlybirds.

He indicated that although some are fixed-wing pilots, most have had no previous aviation, let alone helicopter, background. The story began in 1958. Schramm had always been interested in helicopters but never learned to fly.

“I wanted to go into the helicopter field but felt God wanted me to preach,” he continued blithely. “When it came time to make a decision, God said ‘Build helicopters.”

There were no tablets, no burning bushes, just B. J. and a dream. It took ten years for the neophyte ereator to make a practical flying machine. Apparently he crashed four of his designs before someone convinced Schramm to take lessons and learn how to fly.

If nothing more, the man exhibits both a motivation and a dedication to his calling. Schramm had turned down opportunities to work with established helicopter manufacturers and decided to forge his own way.

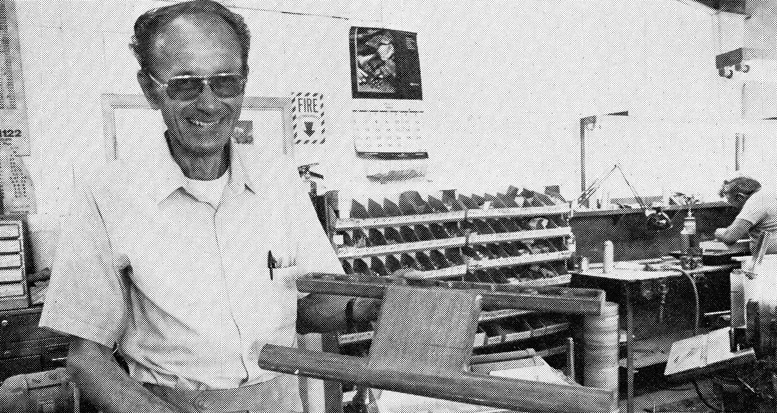

The one man behind the internatinal success of the “Kit Built Helicopter” – Buford John Schramm – AKA – B.J. Schramm (RIP). By leaving the Exec for the builder to complete, Schramm has avoided passing on the costs of certification.

Interestingly, he claims to have no intensely formal engineering or aeronautical background. Having attended a small college in Pasadena, California, Schramm studied for another two years at Cal Poly, Burt Rutan’s alma mater. “I had two years of aeronautical courses but nothing to do with helicopters.” He also had no flight experience.

“I taught myself to fly on El Mirage Dry Lake.” He later taught himself everything else. Although the actual helicopter project began in 1958, the final decision to launch was made in late 1963.

“I proceeded slowly — there were problems in learning to fly a machine I was trying to learn to build,” he continued. “An inner force told me to go on — I knew I had been granted this opportunity.” Apparently some miraculous escapes attest to God’s will as far as Schramm is concerned. “The first ship wasn’t really flyable.”

By 1967, the embryonic company had a workable machine but sold plans only. The name Scorpion was selected—an appropriate appellation for a machine born in the Arizona desert that could kill you as quickly as its namesake if you hadn’t offered the proper respect.

The following year RotorWay was producing a kit helicopter, a unique offering different from the Benson Gyrocopter. Benson, brilliant designer that he is, couldn’t get his marketing quite right.

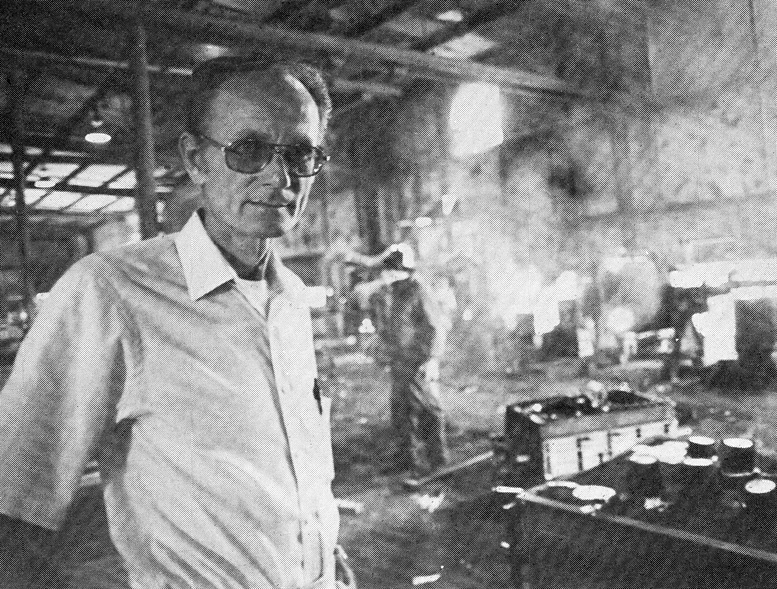

B.J. Schramm in his prime: Schramm’s foundry supplies many of the custom parts for the Exec series of helicopters.

The gyrocopter was effectively a formidable competitive element for Schramm but a wave of accidents, largely due to lack of training rather than product flaws, swept Benson’s company away in the tide.

Schramm persisted. It was an undertaking not to be criticized. Where numerous, so-called “professionals” have come and gone in aviation, Schramm, fifteen years later, holds on tenaciously. He produces an attractive machine and still exerts a presence, if not a market domination.

Whatever you can say about his helicopter, and it does appear to be a fine machine, B. J. Schramm is an astute businessman. All too often in aviation one finds the romantics — those so enamored by their concept that they fail to see the economic ramifications which eventually send them down the tubes.

Schramm, on the other hand, has cleverly supported his vision with good economic sense. He does, however, play his cards extremely close. How many kits have been sold?

“It’s hard to tell because the aircraft is composed of several kits,” he replied. “Many start and never finish so it would be difficult to say how many complete airplanes are out there.” Well how many starter kits have been sold? The reply was equally circuitous. How many Scorpions or Executives have been registered?

“Oh, I don’t really have an exact figure.” Schramm side-stepped once more but indicated that possibly 2,000 two-place machines were in the field along with maybe 600 of the earlier single-place models.

Has he considered going into full scale production with a finished machine? Schramm retorted, “No way!” The certification cost eliminated with an aircraft in the amateur-built (he dislikes the term homebuilt) category is a major factor in supporting RotorWay viability. Cost factors are also held in rein by eliminating the manpower-intensive assembly stages.

By leaving both licensing and labor to the purchaser, cost can be far better controlled. Aside from assembly and costly FAA certified approval, Schramm underlined how difficult it was to make a machine for a price when dependent on outside suppliers.

“You might build one,” he said, “but you certainly couldn’t compete.” Currently RotorWay goes unrivaled as far as kit helicopters are concerned and certainly feels little or no competitive pressure from the certificated community—at least on a cost basis.

To remain in this niche the company makes their own engines and all required castings. “You just can’t be in the kit heicopter business without a foundry,” Schramm noted. “If our engine castings came from outside, fifty percent would be scrapped — we would double our cost.”

He is rather proud of this development — apparently one of only two non-ferrous jobbing foundries in the Phoenix area and located in a burgeoning aerospace community. Of course the corollary to not building helicopters without a foundry is you can’t support such an undertaking on helicopter production alone.

Consequently a good deal of all brass and aluminum alloy output is for other aerospace companies such as Garrett and Hughes, as well as specialist marine requirements. “You can’t afford a foundry with this kind of quality production without outside work,” he said.

The foundry, therefore, seems to be the big money spinner at RotorWay and is organized as a separate enterprise. According to Schramm the helicopter operation makes no profit at all. This state of economics is not necessarily a grim picture but one any knowing entrepreneur might intentionally develop in order to protect his efforts and creatively maneuver his finances.

His description did little to confirm or deny RotorWay’s success. Certainly with a thriving foundry, helicopters could remain a hobby interest. All that could be concluded is that Schramm is still in the rotorcraft business however you slice the pie.

Major concerns for any aircraft manufacturer are the legal ramifications involved with the product. One major suit could easily destroy a small company. For a small company, a plaintiff with a clever attorney could sound an instantaneous death knoll, insurance or not.

The consequence is that RotorWay carries no product liability insurance at all. This sounds like a contradiction but Schramm’s idea of protection is to have nothing to protect. “I don’t own anything. I’m broke — there’s just enough to meet the payroll and pay interest on the loans.”

He adds, “You can sue me but all you’ll get is my underwear. There is nothing left at the end of the month.” The bank, he says, owns all the equipment—liquidation would bring very little anyway. His rationale is that insurance would mean high premiums and this would be reflected in the price of the aircraft.

And even then a juicy case could extend well beyond the insurance cover. The point about product liability is an interesting one. Since the owner becomes the builder, failure of the Exec helicopter in any manner is more difficult to attribute to the manufacture.

In this regard, the idea of an amateur-built machine affords RotorWay a far greater legal cushion. Another factor in considering amateur-built accidents is the fact that the owner has probably contributed six months to a year of valuable time to the project.

The builder might possibly treat his machine with greater respect than most based on the amount of effort that went into creating it. On the other hand, the wealthy professional man who buys a manufactured aircraft largely as a tax write-off may not be so endowed with a similar sense of discipline and responsibility.

In discussing the issue that a costly type certificate was not a factor inherent in the price of the machine, Schramm was quick to respond that this did not reflect on manufacturing quality. “A production certificate is a lot harder to get than a type certificate,” he replied.

“We have 1,800 parts each of which is made with two or three separate tolerances.” The manufacturer was standing by equipment used for checking critical castings. “This will calculate any dimensions to l/15th the thickness of a human hair,” he stated.

What about RotorWay Helicopter’s own quality control and computerized parts tracing? “We have to make a first class effort in both these areas,” Schramm quickly underlined. “If something breaks you can’t recall the entire fleet.”

A computer program was designed to record and track every individual part produced along with a record of its tolerances. Each Exec helicopter is composed of thirty-two kits which are sold in seven groups including the engine.

The engine is, of course, fully constructed. “You buy a group at a time,” Schramm mentioned, “and obviously we sell more starts than finishes.” Some builders will purchase the entire lot at once, but the alternative pay-as-you-go philosophy is obviously attractive.

By financing each construction stage independently the builder can happily take three or four years to complete without heavy financial burdens. This year was the first that a price reduction of $1,500 was offered for someone who buys the entire package at once.

The engine which RotorWay developed is interesting in that its 170-pound installed weight includes a water cooling system. By using water cooling when ram air is insufficient, Schramm reckons he saves seven horsepower adding seventy pounds of useful load to the aircraft.

The engine was designed specifically for this helicopter and outputs a maximum of 152 hp. He went back to the fact that the cost of the engine dramatically reflects in the finished aircraft price. A similar Lycoming powerplant would be priced thirty to fifty percent higher he reckons.

The airframe itself leaves a number of options. In order to qualify as an amateur-built machine, the builder must construct a minimum of fifty-one percent. He can buy a fully welded Exec helicopter airframe, for example, or finish the welding himself.

If he takes the former route he will have to do more work on the rotor blades, however. The flexibility allows the constructor to take advantage of the best skills available. Schramm estimates approximately 500 hours to complete the Exec model—the latest in the RotorWay line.

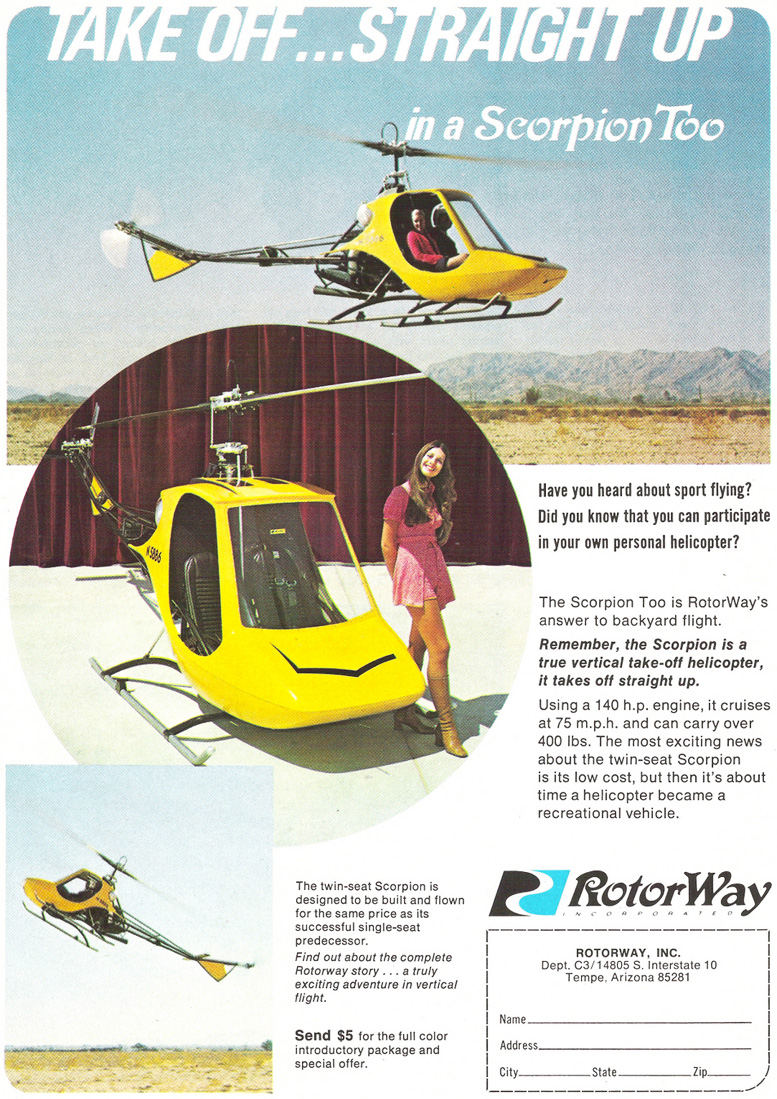

Originally starting with the single-place Scorpion (priced in 1968 at $12,000), the helicopter went through a range of developments resulting in the two-seat Scorpion II helicopter in 1971. Further (improvements led to the final Scorpion 133 helicopter.

In 1981 the Exec was born, a racier looking machine with a fully enclosed engine, removable cabin doors and sleek aerodynamic styling. Although the Scorpion helicopter is no longer in production, all parts are fully supported.

Schramm was quick to note that since his first effort the economy has seen a fifty percent devaluation in the dollar which would adjust the cost of the present helicopter to nearly that of the original.

The fuselage of the Exec helicopter consists of thirty-three fiberglass parts weighing seventy-five pounds. “You don’t have to make any fiberglass pieces yourself,” states Schramm, “and the alignment holes match up to within 1/8 of an inch.” All that’s left is cleanup, sand, pop rivet and paint.

Lap joints and jaggles are done for you so the result is a smooth, flush finish. According to the manufacturer, all parts are turned to final size so all that remains to do is make a smooth finished edge.

The Exec helicopter, with its 102 mph VNE, uses an all-metal rotor system with a bonded aluminum trailing edge similar to the Hughes 300 helicopter. The body is all fiberglass covering a 4130 steel tube frame. The original design Schramm claims is his, developed in conjunction with outside consultants.

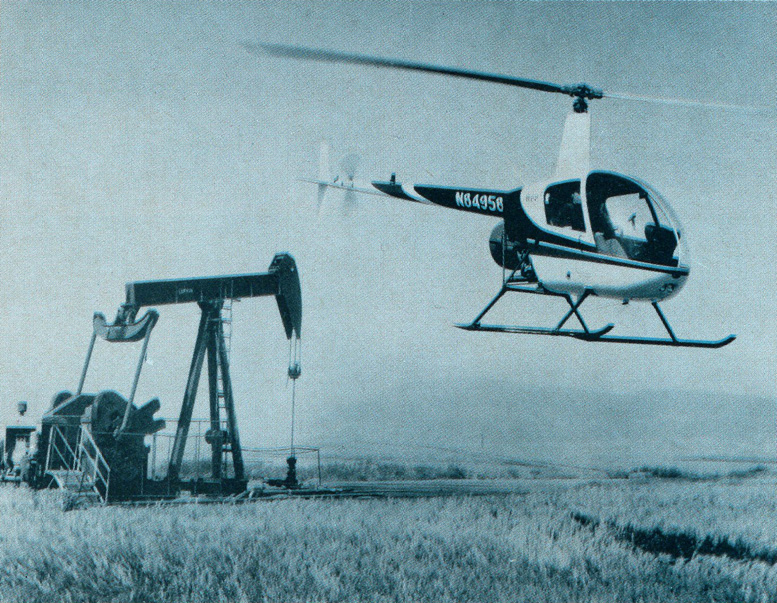

Robinson R22 commercial helicopter personal transportation – the more expensive option!

“We wanted an enclosed helicopter with aesthetic appeal,” he noted. By using a monocoque tail boom and a modified frame he was able to keep the same empty weight as the Scorpion helicopter but increase the speed to over 100 mph.

“We changed the controls to dual push/pull cables rather than using — rods and bellcranks.” This simplified the collective and cyclic systems to about 1/10 the complexity but retained the dual redundancy of two cables. Elastomeric bearings were added to the rotor head which means longer flying with less fatigue offering for greater utility value.

Ninety-five percent of the 1,800 Exec parts are made by RotorWay. The Exec helicopter canopy, laid up by hand, is also produced in house. The shape gives an attractive quality to the helicopter and combines that egg-shaped appearance of the Robinson and Hillman machines.

Tooling required for such an effort is what keeps the competition at bay according to Schramm but whether or not there is room for competition in this narrow marketplace remains to be seen. “God gave me this market and I’ve been there ever since,” he said.

Schramm did indicate that the personal, amateur-built area is becoming fairly saturated. For this reason he is exploring further uses of the machine. Floats, a spray boom and a camera platform mount are all options for semi-commercial applications. Inflated, the Exec helicopter floats weigh twenty-five pounds each.

The spray attachment includes two ten-gallon tanks which take a low volume concentrate. Rotor heads atomize the spray efficiently enough to allow a 160-acre coverage. One would expect a fair amount of business transport use and some utility functions.

Farmers, of course, can buy the spray unit which makes the Exec an efficient crop duster and with floats available fish spotting becomes practical. The 400 pound payload is restricting for any larger commercial application, however. Schramm underlined the biggest problem in the small, light helicopter field as training.

“The difficulty faced by Robinson was that a lot of doctors and lawyers started buying helicopters and wiped out. This gave the manufacture a bad accident track record and stifled sales.” In an early stage of Scorpion development he realized that most wouldn’t follow the same learning route that he had taken.

“I knew that people would need training in type. The question was, how do you do that in the amateur-built category?” In 1975 a training program was started at the RotorWay factory devoted to teaching Scorpion builders how to fly their own machines.

Apparently Exec helicopter 1,000 owners have been through the course which involves not only flight training but construction and maintenance on RotorWay equipment. The training program is broken into two or three one-week periods.

After the builder has completed ninety percent of his machine he can come to the Scorpion Sky Center for an initial instruction period to solo stage. He then returns home to practice the solo maneuvers and comes back for the next level of training.

“We devised a new concept for teaching people to fly their own machines,” Schramm emphasized. “We broke flight training into two distinct phases. First, hover in ground effect and, later, all the climbout maneuvers.”

By forcing the student to initially become proficient in ground effect handling, Schramm feels everything else becomes second nature. “This is a basic philosophy shift from military or commercial programs — we worked it out with the local CADO.”

Currently eight ships are available in the dual training fleet with two full time instructors and an inhouse designee/examiner for issuing licenses. The cost of the program is now included in the price of the machine but the course is also opened to second owners on a separate fee basis.

Prior to the training program, Schramm recommended that builders learn on the Hughes 300 or Brantly B2B. “This proved relatively unsuccessful,” he noted, “because ours was a smaller, lighter helicopter with different control feel.” Schramm discussed the philosophy behind his Exec helicopter.

“If you’re too performance oriented you start getting fatigue and if you’re not performance oriented you lose sales. Either way you’re out of business — it’s a very fine line.” He noted that the biggest proportion of the flying market is interested in helicopters but no one offered the proper vehicle. “From an evolutionary standpoint helicopters are still in the dark ages.”

He added, “The Apache helicopter is a fantastic aircraft but still a scaled-up version of the Hughes 500 helicopter with a lot of electronics. It has no fewer mechanical parts than any other helicopter.” Schramm stated, “What we have to do is build a helicopter in a more sophisticated context that makes use of available manufacturing technology.” RotorWay stands in a class by itself.

“A large company could do what we’ve done but it would require a 10-15 million dollar investment,” commented Schramm. “There just are not the financial rewards here to justify that.” He talks about economic survival as a very fine path.

Presently his computer tracks progress on the fifty plus workers and Schramm insists that if he is more than two percent off in his production figures the company would go bankrupt. It is clear that one of Schramm’s motivations is his love of rotorcraft but this alone can’t substantiate a business.

One supposes that when you have a good grip on, at best, a tenuous market then the idea is to discourage anyone else from horning in. Tooling available in the 75,000-square-foot factory could produce 500 to 1,000 units per week but Schramm wouldn’t quote figures. All he would say is, “The market is saturated.”

It would seem that only two to three helicopter kits per week roll off the line so perhaps his parting comment should be taken quite literally, “If you want to make a profit, stay a long way away from aviation.”

Be the first to comment on "BJ And The Exec Helicopter Interview"