Canadian Home Built Helicopter

By Don Dwiggins – 1986

Although it was never developed into commercial applications, this counter-rotating, ground-shaking contraption is now recognized as Canada’s first successful rotorcraft – (article 1986).

The year 1939 is best remembered as the start of World War II, when in September, German panzer divisions and formations of Stuka dive bombers blitzed through Poland. That same year in America, Igor Sikorsky flew the world’s first successful helicopter—his VS-300 Ugly Duckling—giving a new dimension to airpower.

In a face-to-face meeting with Sikorsky, another American inventor, Dr. Igor B. Bensen, was so impressed he formed his own aircraft company in Raleigh, N.C. to develop a mass-producible “People’s Flying Machine,” capable of door-to-door transportation.

Since then, the name Bensen is associated with homebuilt rotary wing craft; Dr. Bensen’s firm developed no less than 18 prototype models of both helicopters and gyrocopters.

During this time, three young Illinois farmers, transplanted to the Red River Valley country of Canada’s Manitoba Province, were making history of their own—a history, until now virtually unknown to the “outside” world—with the development of an amazing rotary-wing machine that is now recognized as having achieved Canada’s first controlled. manned vertical flight.

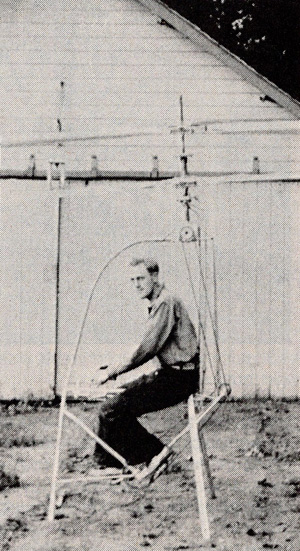

To compete for Kremer Prize for man-powered flight, Doug Froebe converted his coaxial helicopter into a man-powered “ornicopter.”

The brothers; Douglas, Nicholas and Theodore Froebe, were inspired as kids by watching training planes of the 1920s flying over their farm near Rantoul Air Base. When they settled in Manitoba, they became homebuilders of a different sort, designing and building successful motor scooters—a forerunner of the modern snowmobile.

One day they saw an ad in Mechanics Illustrated for a Heath Parasol plane kit: they knew they had to build one. They sent for the kit and got the parts but none of the trio knew how to fly. So Doug Froebe looked up a pilot in Winnipeg-Connie Johannson—and took some lessons in a Gypsy Moth.

But when they tried to get the Heath Parasol off the farm, Froebe found it was tail-heavy, so they simply moved the landing gear back under the CG, which worked well. When Froebe finally got airborne, he found the Heath was badly wing heavy, which they fixed by twisting the wing with enough warp to keep things level.

The joy of flying was almost too much for Froebe—on his first flight away from the farm he found himself staring right into a maze of high-tension wires. He did what came naturally and shoved the stick full forward. The brothers scooped up the wreckage and stuck it away in the barn, and wondered about something that could fly straight up.

They read about a helicopter developed in 1923 in the United States by Emile and Henry Berlinger that used a four-bladed co-axial arrangement, later modified to a side-by-side configuration with large fixed wings for control. It flew—sort of—but the Froebe brothers shook their heads.

“We came to the conclusion that to overcome the gyroscopic tendency of turning the four blades, it would probably kill all the horsepower,” Doug said in a 1979 interview.

So they became snowbirds in the winter of 1936 and went south to California, where they met Walter H. Barling, a British engineer who had retired to California in 1919. The Froebes discussed their idea for a helicopter with Barling, a man with plenty of imagination. Barling suggested that they settle in California and build the aircraft with him, but they refused.

They then visited Charlie Babb, in Glendale, the world’s biggest airplane junk dealer, and drove home with a carload of equipment, including a Gypsy Sirius engine from a wrecked Great Lakes trainer with only 17 hours on it, for which they paid $100.

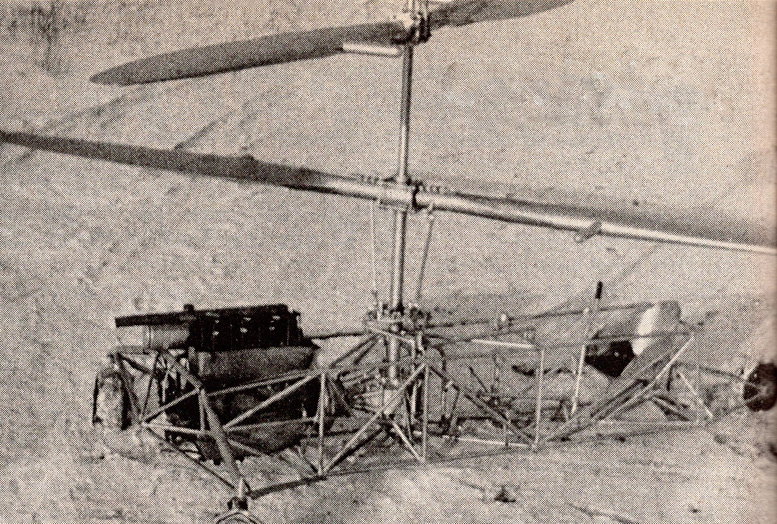

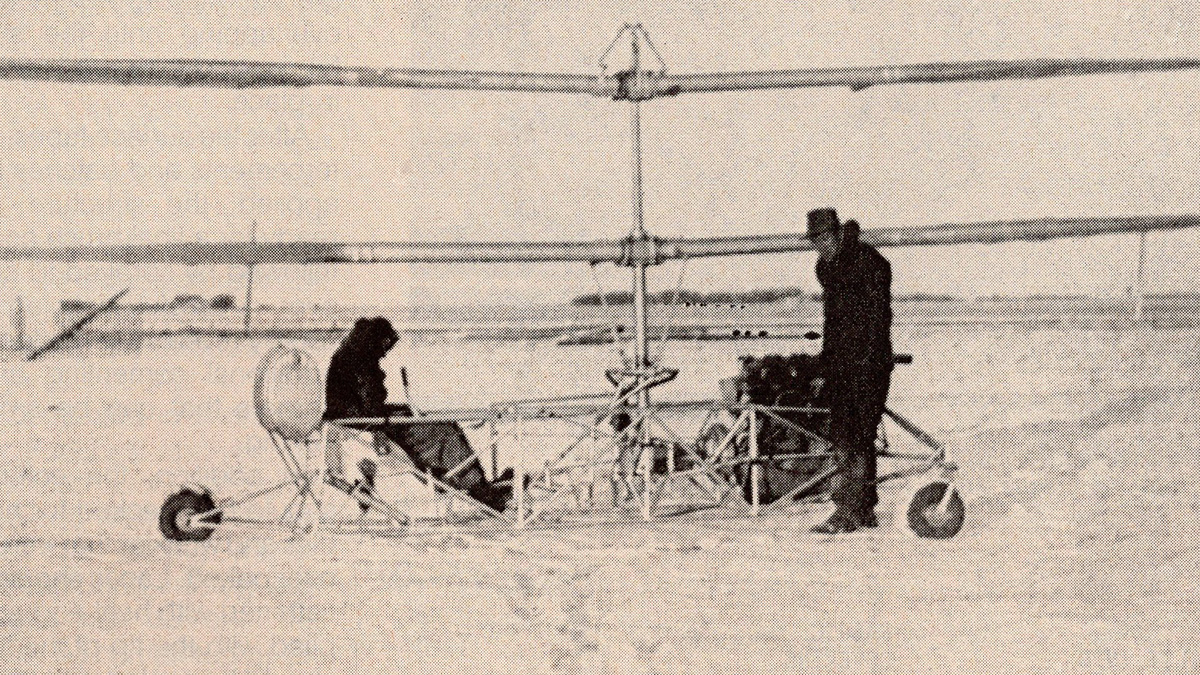

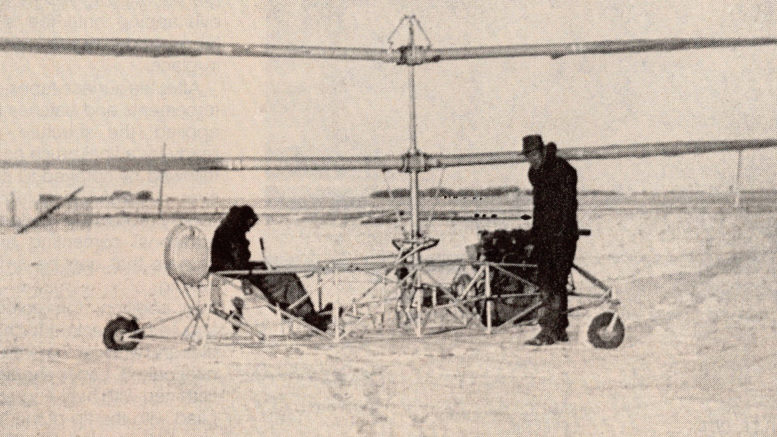

Back in Manitoba, they corresponded with a professor of engineering they’d met at the University of California, Berkeley and got some data on centrifugal loads on helicopter blades, they then began to build their contraption – Canada’s first successful rotorcraft.

They bolted the engine directly to the gearbox, then decided to install rubber couplings from a Caterpillar tractor. The engine just jumped around and wouldn’t start, so they substituted a Ford truck flywheel and clutch. But on each power stroke the whole engine still jumped up and down.

On initial trials, however, Doug Froebe got the thing up to an altitude of almost 3 feet, but she was nose heavy, so they moved the gas tank to the rear. That, coupled with a switch to 28-foot diameter blades from 20-footers, upped the ceiling to approximately 5 feet; they were on their way. In all, they logged a little more than 4 hours of flight time.

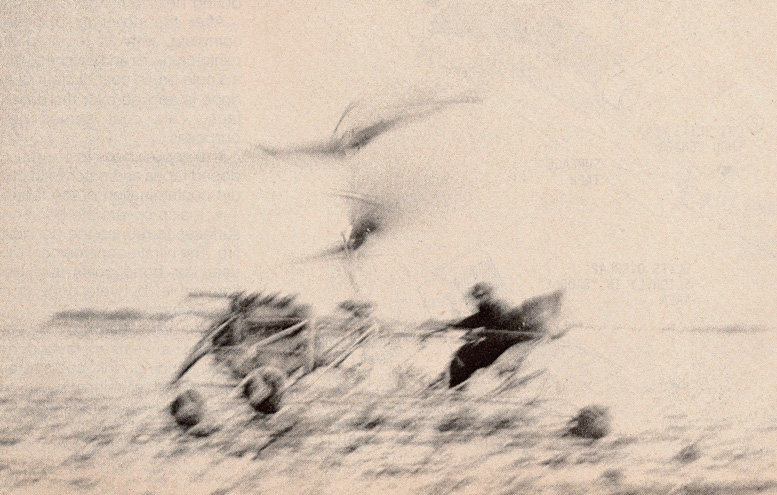

One thing scared the Froebe brothers—the startling sound of the rotor tips reaching sonic speed, bounced across the farm, echoing between the granary and the pool elevator, sounding like a raging battle. Nevertheless, it flew, and they spent $250 to have a patent attorney look up prior patents on choppers. There were so many though, that they said to heck with it.

The full story of the Froebe helicopter might have vanished from aviation history had it not been for the energetic work of a small group of enthusiasts in Winnipeg, called MARG—Manitoba Aircraft Restoration Group—dedicated to retrieval of wrecks of early aircraft.

One of their first efforts was to probe the depths of Cormorant Lake in Manitoba in 1973, to find the wreckage of a long-lost Vickers Vedette. Next, they found a 1835 Bellanca Aircruiser of Canadian Airways up in Pickle Crow, Ontario.

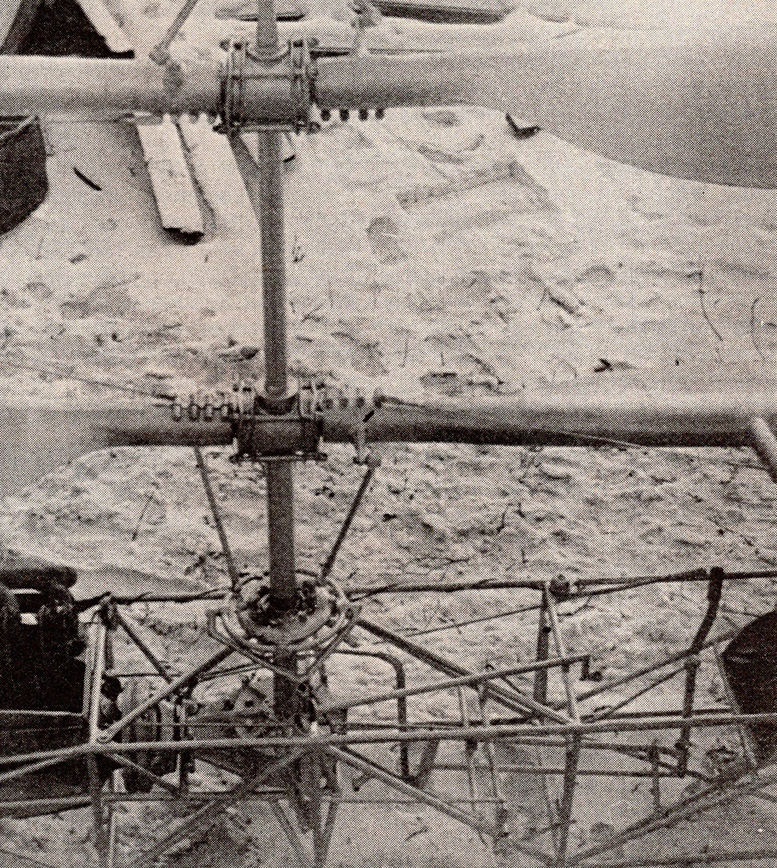

The Froebe rotor hubs were well designed but a tad on the heavy side.

Today they’re still hunting relics of the old bush flying days. More than a score of oldies were recovered and refurbished and are now on display in Manitoba’s Western Canada Aviation Museum, where executive director Gordon C. Emberly showed us the original Froebe machine.

Emberly also showed us a copy of an interview with Doug Froebe, taped on July 18, 1979. in which the origin of their helicopter design was recalled: “The design was just logical thinking, you know, co-axial design . . reflecting the old Avro Avions that just had ailerons on the lower wings.”

“We figured if we could control the cyclic pitch control on the lower wings, it would be sufficient to give lateral control and longitudinal control of course, the directional control is by torque, gained by increasing the top and decreasing the bottom through foot controls. There was a crank-operated collective pitch control, through which you could increase the blades together on each flight.”

In the interview, Froebe revealed that the front gear oleos came from a Boeing tailwheel they found at Charlie Babb’s along with the gas and oil tanks. The chrome-moly tubing they bought from a Winnipeg aircraft supply house, which helped them make up the rotor blades, used a NACA airfoil.

To solve a serious vibration problem on Canada’s first successful rotorcraft, Froebe’s brother Nick took out some of the rubber rotor hub shock mounts and added mass balance along the leading edges of the vanes. It worked for a while, but one day one of the weights flew off and almost hit a cow 100 yards away.

For the transmission, Doug recalled, they stripped parts from a Chevy truck transmission and refashioned the crown and pinion gears to fit a welded gear case “just the way a blacksmith would do it.” said Froebe. The craft still had the shakes, however. and once the gears slipped a cog and everything got out of sync. To alleviate this, they bronzed the studs that held the case together.

“We should have realized at the time that our problem was in the hub” Froebe said. It was affected by the power cycle of the engine. We’d just dampen the power, which probably was a good thing, because somebody might have broken their neck.

“The ball bearings in the hubs eventually broke—you can still hear the grinding when you turn the blades pitchwise.” So that discouraged us from continuing, and of course, the war broke out in 1939, and farming became more important. Then I went south and got a job working in the shipyards in Oakland. California.

The Froebe brothers coaxial helicopter; built in 1938-39, is recognized as the first Canadian vertical lift aircraft to have successfully flown.

When the war wound down, Doug said, the Froebe brothers were approached by a group of five financial experts who said they would put up $100,000 if the Frobes could get their aircraft off the ground again. They were excited, until they read the fine print—the backers would actually only put up $50,000. and the Froebes would get only one-fifth of that for all rights: so they said no.

They then heard about the $125,000 Kremer Award put up by a British industrialist. Henry Kremer, for the first person to fly a figure eight in a man-powered aircraft. Thus was born a new homebuilt project, the Froebe man-powered ornicopter – part ornithopter and part helicopter, a chopper with flapping wings.

Doug said they looked at an assortment of insect-wing designs, settling on the common housefly. Friends at UC Berkeley sent them a blow-up of a photo of a fly’s wing, from which Doug and his brothers actually built an ornicopter with a 20-foot wingspan.

“By flapping the wings,” said Froebe. “I thought we could eliminate the torque problem. I had two wings flapping down and two wings flapping up at the same time.” It weighed only 130 pounds.

In 1976 I decided to try it out at our farm in Homewood, Manitoba. I never did get it off the ground in calm air, but since then, I’ve been thinking, “why not do what the hang glider pilots do—leap off a hilltop?”

“I actually got the wings to flap about 25 to 30 times a minute just by pedaling, and the wing loading was equal to that of a high-performance sailplane, so that it had a nice, slow sink rate. But at 78. I’m too old and too lazy to experiment any further, so maybe I’ll put it on display at the Western Canada Aviation Museum. Maybe it will encourage some young engineer.”

“I maintain that the ornicopter would be stalproof, because once a wing stalls, you peddle it another flap and your lift is reestablished.”

The rotors whipped around so fast that the tips approached the speed of sound, setting up a heck of a clatter and vibration, scaring the photograph as well.

Be the first to comment on "Canada’s First Successful Rotorcraft"