From Gyrocopters To Kit Built Helicopter Mini 500

NOTES: Giving Credit

KITPLANES: February 1993

The cross reference to the 1993 Homebuilt Aircraft Directory in the December ’92 KITPLANES credits Agusto Cicare with the design of the Revolution Helicopter Corp. Mini 500, and that elicited a cry of foul from Revolution, which says that its president. Dennis Fetters, designed the Mini 500.

Fetters flew Cicare’s CH-6 single-seat helicopter at Oshkosh ’90, and Cicare and Fetters originally planned to collaborate on a kit version of the Cicare machine.

However, the proposed partnership dissolved. Fetters began work on his Mini 500 Helicopter, and Cicare’s new version—the CH-7 Angel single-seater — is being kitted by an Italian company.

The Revolution Helicopter Corp. claim to design of the Mini 500 Helicopter has been strengthened by the issue of a United States patent to Fetters on the helicopter’s control system.

Fetters’ patent attorney confirmed to KITPLANES that the U.S. Patent Office has approved the application and has issued a patent number. For more details on the Mini 500, see LeRoy Cook’s article, which begins below the editors comments.

Revolution Helicopter’s Mini 500 is a single-seat sport helicopter that requires conventional training to fly. Fetters

hovers the Mini 500 in an early test flight.

EDITOR: This is a bone of contention for myself! Personally I find this whole situation insulting to Mr. Augusto Cicare – a well established designer and inventor of many helicopters, and even engines.

Basically, Dennis and Augusto had an agreement to work together on the Mini 500 Helicopter project using the CH6 helicopter as inspiration. After a falling out, Dennis designed his own version of the CH6 cyclic system, then proceeded to race to patent his design before Augusto.

Dennis is a savvy business man “first” and gyro designer/salesman “second” and “thirdly” a helicopter designer/salesman. His idea for the Mini 500 was indeed “revolutionary” – pardon the pun.

While most patents and designs are usually based on an existing idea or design – Dennis should be giving credit directly to Mr. Cicare as the inspiration behind his Mini 500 helicopter control system.

I wont criticize the many minor faults the Mini 500 was to reveal during it’s evolution (most first issue/versions go through teething problems) – though as we all know, it took a very long time for Dennis to acknowledge them and address the updates and modifications.

Ultimately, being a salesman first, these delays led to the demise of his Mini 500 kit helicopter – then he went back to being a salesman/litigator and suing anyone that talked ill of he or his design.

It’s a little known fact that the Angel CH7 helicopter also had many issues, but they were promptly addressed as they were encountered and clients advised of required updates to their craft.

A few years ago, Dennis Fetters’ Air Command gyroplanes took over the leadership position in low-cost rotary-wing flight. A huge number of Commander gyro kits were sold, providing an economical way for builders to get airborne under a set of rotors, thanks to forward thrust supplied by a powerful, lightweight Rotax two-stroke engine.

Fetters was not satisfied for long with Air Command’s success. He grew steadily more interested in helicopters, eventually selling his nine-year-old company to work on powered rotors. He appeared at Oshkosh ’90 with a single-seat helicopter from Argentina, putting on an impressive show before a packed gallery in the ultralight/rotary wing display area.

But he says he was unable to complete an arrangement with Agusto Cicare, the machine’s designer, and he consequently went to work on his own similar design, which—without apology to McDonnell-Douglas—he calls the Mini 500. As with his previous equipment. Fetters likes his machines to fly well and look good.

EDITOR: Surprisingly, Canadian Home Rotors were asked to change their “Baby Bell” helicopter name by the Bell Helicopter company, and they did so – resulting in the Safari kit helicopter.

Accordingly, the Mini 500 Helicopter was given a fully enclosed cabin rather than an open bucket seat, and it was to share certain other Fetters desired features like a rotor disk that’s safely above normal head height and a control system with few exposed parts.

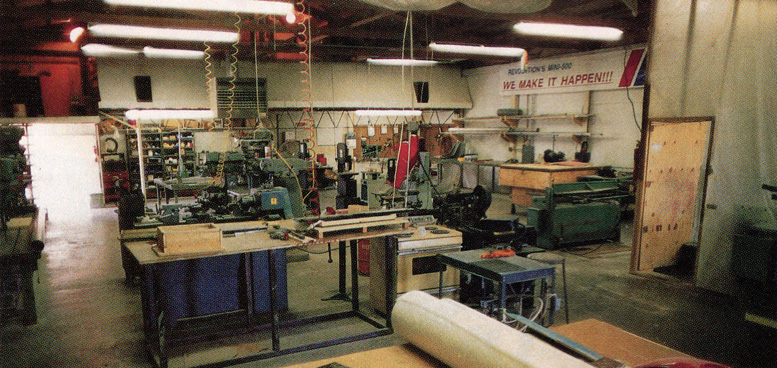

For months, the Fetters team has worked at setting up production tooling while it simultaneously developed the prototype. This risky, time-consuming procedure means there can be no bread-boarded prototype to dazzle the crowds while a salable production version is being finalized.

Instead, the first Mini 500 Helicopter has been tweaked and defined while molds were created for the fiberglass cabin pod, a bake oven was built for the rotor blades, and the engine installation was refined. An advantage of working from production tooling, of course, is that kit deliveries will begin much sooner after the aircraft’s first flight.

The New Company

Revolution Helicopter Corp. was started in January, 1991. Fetters was impressed with the market response for a small, low-cost, true helicopter, and the project attracted considerable early interest. There’s something about homebuilt helicopters that always seems to fascinate a segment of the public that has little interest in fixed-wing flight.

Perhaps it’s the potential freedom of being able to lift off vertically from one’s backyard or settle onto a mountain meadow with-out runways or other support facilities. In any event, Revolution had received almost 100 orders for the Mini 500 Helicopter at the time of our visit in mid-1992.

The orders generated so far were primarily garnered by direct contacts, and all deposits are placed in refundable escrow accounts. Unfortunately, most would-be purveyors of homebuilt helicopters seem to produce nothing more than information packets.

When you ask if the machine has been flown, the event is always eminent or shrouded in secrecy. Few, if any, of these paper designs actually make it into the air, despite their steady advertising schedule. Fetters was determined to wait until he had a flying production prototype before heavy promotion began.

Daylight appeared under the Mini 500’s skids for the first time last May 12 when it lifted off in tethered flight, and after FAA inspection was completed on June 5, a full flight test program began. If all goes as planned, kit production is expected by the end of 1992.

Seeing Is Believing

As soon as the prototype was flying, I dropped in at Fetters’ plant near Liberty, Missouri, to check it out. The visit included a short tour of the factory and a demonstration flight. As the Mini 500 is a single seater, I merely observed the test hop from the nearby ramp, but it was evident that Fetters was in his element as he put the baby bumblebee through its paces.

The Revolution Mini 500’s deja vu shape is hardly a coincidence. As long as Fetters was going to the trouble of designing a suitable housing for the cockpit, he figured he might as well make it recognizable.

The teardrop pylon around the main rotor mast, the outline of the vertical and horizontal stabilizers, the faired skid legs, the blunt nose with an egg-shape fuselage—all are reminiscent of the early Hughes 500 Loach, right down to a fake tailpipe opening.

The Power Package

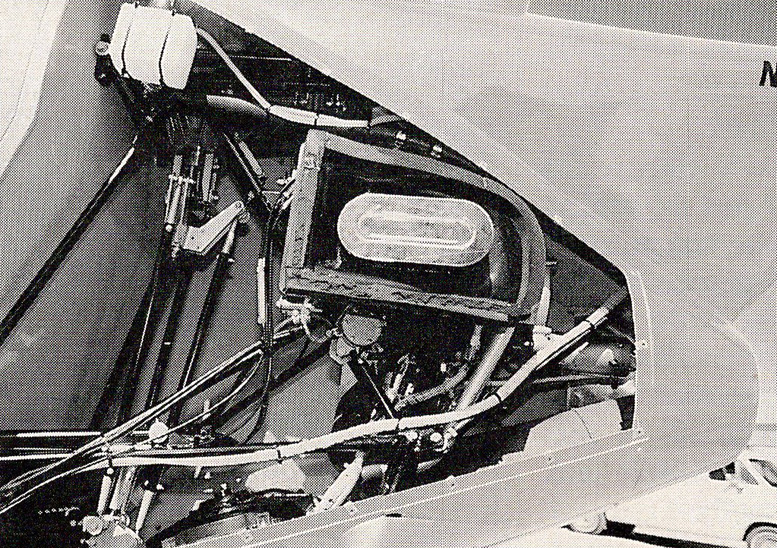

Instead of an Allison 250 turboshaft, however, a 67-hp, liquid-cooled Rotax 582 is nestled into the tubular engine and transmission support structure behind the cabin, its muffler outlet aimed right through the jetpipe opening. The radiator is concealed under the lower panel surrounding the engine, with an airscoop beneath the radiator to boost cooling in forward flight.

A custom 11-blade electric fan engages to force air past the cooling tubes when coolant temperature exceeds 180°F, cutting out when the coolant drops below 160°F during forward flight. The radiator’s thermostat is set to open above 130°F. The 15-gallon fuel supply will be contained in a composite saddle tank above the engine, near the e.g.

Rotating Blades

The heart of any helicopter is its rotor system and associated pitch control method. The Mini 500 Helicopter uses a two-blade teetering rotor with pitch-change linkages running aft from the cabin, up through the center of the transmission housing and through the rotating mast.

What Fetters calls a unique yoke control device in the lower fuselage replaces the swashplate usually seen under a helicopter’s rotor head, allowing pitch changing inputs to take place inside the engine/transmission compartment. A patent for this arrangement is pending, he say.

Revolution makes it own rotor blades, curing 10 blades at a time in the special oven it designed for the task; the blades use an aluminum D-section leading edge spar attached to a composite aft section with a foam-filled core.

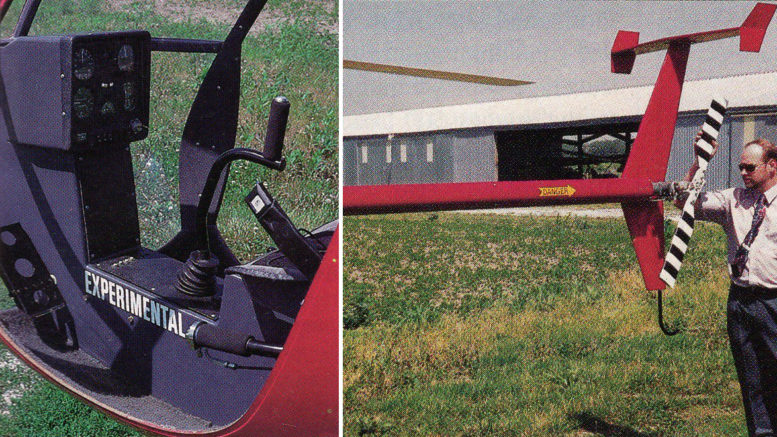

The tail rotor also originally employed an innovative control method. Mounted high at the end of a tubular tailboom to keep it out of debris and brush, the tail rotor was controlled by unboosted hydraulics operated by anti-torque pedals.

A balanced loop of hydraulic fluid opened two cylinders that opposed each other when the pedals were moved. But by Oshkosh time last summer, the hydraulic tailrotor control had given way to conventional mechanical linkage with the pedals.

Fetters claims that the 19-foot rotor disk of the Mini 500 Helicopter, with its tips operating roughly 8 feet above the ground, gathers no benefit from ground effect, a characteristic he sees as an advantage in pinnacle operation when a barely-hovering helicopter moves over the edge of a precipice and must pick up translational lift quickly or descend to maintain rotor rpm, probably both.

The Mini 500, he says, should be less susceptible to such risks.

More on Power

How can a 67-hp engine possibly generate enough power to fly a helicopter, when most homebuilt rotorcraft need twice that much to get airborne? The answer lies in the Mini 500’s light empty weight, targeted for 330 pounds, and in directing the power to the rotors as simply as possible.

The primary takeoff from the Rotax 582’s output shaft is through a Kevlar-lined multiple V-belt drive, absorbing power pulses as the power goes to the transmission gears. Helical-cut gears drive the straight-out tail rotor shaft that turns the 90° gearbox to the tailrotor blades.

Getting at Things

Access to the Mini 500 Helicopter engine/transmission compartment is through quick-release panels initially, and further disassembly can be done by sliding the tail-cone housing aft along the non-tapering tailboom. The cockpit enclosure is not removable.

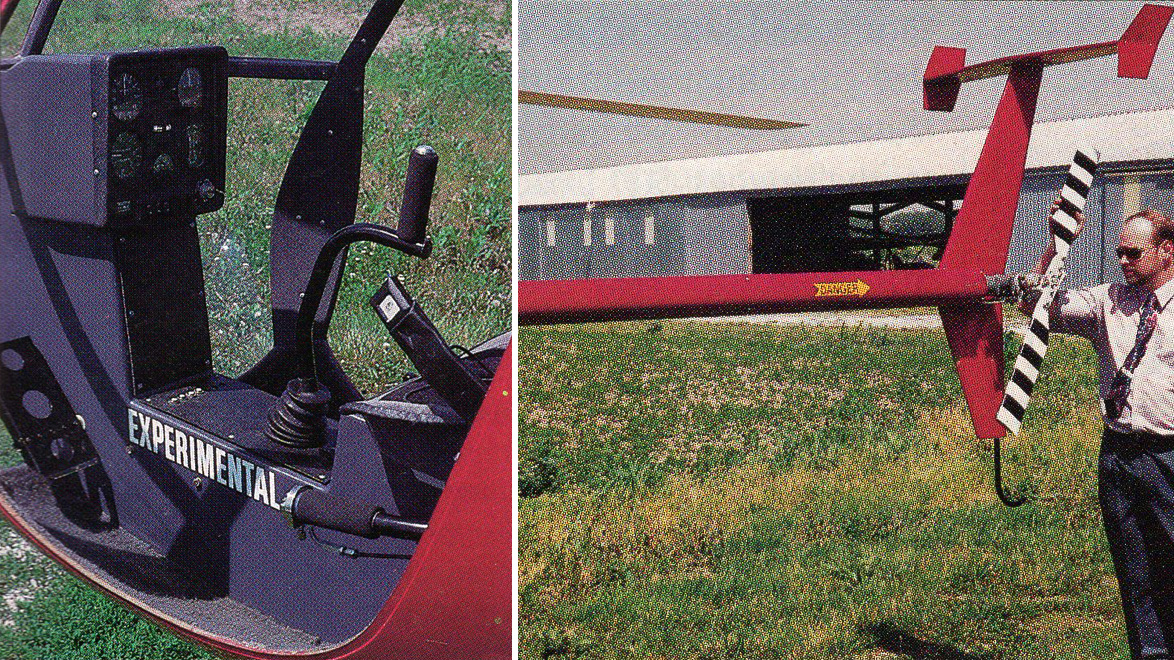

Rather, it is an integral part of the aircraft’s structure, its central tunnel adding a crashworthy keel framework to which the pilot’s seat, controls and instrument panel attach. Revolution manufactures the composite cockpit shell as well as the clear windshield and door panels.

The relatively high skids of 2-inch aluminum tubing are suitable for utility operation, with ground-handling wheels attaching just aft of the empty e.g. so the helicopter can be slipped easily in and out of a storage hangar. Other than the Rotax 582 powerplant, all components of the Mini 500 are designed for a 2000-hour time-before-overhaul.

Keeping It Simple

Fetters claims to have drawn his Mini 500 Helicopter aircraft with one-eighth of the parts count found in most other helicopters, and consequently he is quoting a building time of only 40 to 50 hours.

There is a minimal amount of welding and riveting to be done, bolt holes are matched to dimples in the adjoining part to simplify drilling and finishing, and the rotor blades attach with only two bolts apiece. The cabin housing is already finished in gelcoat, available in five colors: the prototype’s red plus white, blue, black and primer gray for custom painting.

The instrument panel contains standard rotorcraft gauges: an airspeed indicator with readings from 20 mph, a magnetic compass, altimeter, slip ball, VSI, coolant temperature and a dual-reading tachometer for engine and rotor rpm, expressed in percentages of 100% rpm, turbine style.

Electrical switches will go across the lower edge of the panel, with radios stacked below the Mini 500 Helicopter flight gauges.

Standard helicopter controls are provided: a cyclic stick between the pilot’s knees, a collective stick beside the pilot’s left leg with a twist-type throttle in the handgrip, and anti-torque pedals flanking the center console. No cyclic trim or friction locks are installed at present, but these may be added later.

The prototype’s lighting consisted of a landing light in the lower part of the bubble and red and green position lights on the forward tips of the skids.

Fetters says he’s designed the controls to feel very much like the Robinson R22, currently the least expensive and most popular training helicopter. As the Mini 500 is licensed in the Experimental/Amateur-Built category, it will require at least a student pilot’s license with a solo signoff from a helicopter CFI every 90 days.

Private or commercial pilots with a helicopter solo endorsement in their logbooks will be able to fly the Mini 500 without a helicopter rating because it can’t carry passengers. Fetters recommends training to the solo level or beyond in a Robinson before transitioning to the Mini 500.

Launch the Mini 500 Helicopter

Our walkaround done, Fetters donned his hardhat and slipped into the cockpit to demonstrate the Mini 500’s agility. The seat adjusts over a 3-inch range to accommodate most pilots.

Controls check, tailrotor clear, a pull of the choke and energizing the electric starter caused the Rotax to whir busily to life. Engaging the transmission is done by latching a lever overcenter on the right side of the console; with a shriek from the idler cam pressing into the rubber belt, the blades started turning.

Vibration is the constant bugaboo of helicopters, due to all the natural frequencies generated by rotating parts in close formation, and the Mini 500 Helicopter undergoes a normal amount of shaking and humming as it builds up to its flight configuration.

As soon as the engine temperatures were up to normal, Fetters pulled pitch, lifting the collective as he smoothly applied power and picked the helicopter up into a 3-foot hover.

He paused briefly to check the cyclic stick’s position and available power, then bent the Mini 500 over to head for open maneuvering space. With a blur and whoosh, he was off to cavort around the vacant ramp, showing us that the Mini 500 Helicopter could quick-stop, back up, fly sideways and pedal turn like a pinwheel. Being careful not to ding up his one-and-only example.

Fetters eased to a precision landing on an old pump island beside the ramp. Clearly, he was the master of the new, barely tested machine, and was using the demonstration flight to check for any shortcomings he could find. As an example of the input from flight tests.

Fetters has already announced that a rotor brake will be an option to shorten the spin-down period after landing. Fetters says the center of gravity was right on the money when the aircraft first flown, and even the blades tracked perfectly the first time out.

At the time of our visit, about 4 hours were on the Hobbs meter, and the aircraft had been taken up to 50 mph during normal controllability checks, with no major surprises.

Subject to flight test verification, a maximum speed of 95 mph is predicted for the Mini 500, with a cruise speed of 75 mph. The onset of retreating blade stall is way up at 150 mph, far outside the normal operating envelope, and the rate of climb at sea level is expected to be 1100 fpm.

Following Up

Oshkosh ’92 was a source of both triumph and consternation for Fetters. The Mini 500 Helicopter had accumulated 25 hours and forward speeds to 60 mph by then—proving it is a viable product—and the company added sales to its customer list.

But 25 hours was insufficient time and testing for a public flight demonstration at Oshkosh, according to both the FAA (which required a minimum of 40 hours to issue a permanent airworthiness certificate) and to Fetters, who said he is a long way from completing his required testing.

Adding to the consternation at Oshkosh, no doubt, was the Elisport CH-7 Angel, which is Agusto Cicare’s single-seat helicopter with a small streamlined pod.

The CH-7 is being produced in kit form in Italy, and its Italian demo pilot flew extensively at Oshkosh, even performing a spiraling autorotation all the way to touchdown.

For his part, Fetters is pleased at the interest shown in single-seat helicopters, and he is also pleased that his competition — the CH-7 kit —sells for about $10,000 more than the Mini 500 kit.

Since Oshkosh, Fetters has flown a lot, but he says improvements and tests continue. The hydraulic tail rotor pitch control has been replaced by a more-conventional mechanical link with the pedals that works as well as the hydraulic system, weighs the same and is, no doubt, less expensive.

Most recently, Fetters has changed his Mini 500 Helicopter main rotor molds to add twist (washout) to the blades, which he says will improve the already adequate autorotation capability of his little ‘copter.

As Seen from Here

At long last, amateur helicopter builders may have a person to take them seriously—someone with enough experience in both rotarywing flight and kit production to bring the project to fruition.

If you want to see the Mini 500 fly, set up a visit to the factory , where all domestic sales are being handled. It would be smart to bring along money for a deposit, because you’ll be impressed.

Power comes

from a liquid-cooled, 67-hp, two-stroke Rotax 582 that is tucked into the tailcone.

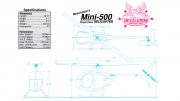

| Revolution Mini 500 Helicopter (1993) | |

|---|---|

| Kit Price | $24,500 – (includes engine, electric starter, basic instruments, paint and interior) |

Specifications |

|

| Rotor diameter | 19 ft |

| Length | 18 ft |

| Height | 7 ft. 2 in |

| Landing gear type | Skids |

| Skid base | 5 ft. 3 in |

| Seats | 1 |

Weights and Loadings |

|

| Gross weight | 820 lb |

| Empty weight | 330 lb |

| Useful load | 490 lb |

| Fuel capacity | 15 gallons |

| Payload (full fuel and oil) | 400 lb |

Engine |

|

| Rotax 582 | Two cylinder, two-stroke. liquid-cooled, 67-hp |

Performance |

|

| Maximum speed (sea level) | 95 mph |

| Cruise speed (75% power) | 75 mph |

| Range (no reserve) | 225 s.m. |

| Rate of climb (sea level). | 1100 fpm |

| Service ceiling | 10,000 ft |

| Hover ceiling IGE | 5500 |

| Hover ceiling OGE | 7500 |

| Source of information: Revolution Helicopter Corp. | |

Most Mini 500 kit parts including composite rotorblades will be made in the company’s shop at Liberty Landing Airport, Missouri.

Be the first to comment on "Gyrocopter King Moves To Mini 500 Helicopter"