Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Pilot Report

September 1969

Not just a pretty face, this candidate for queen of the piston hover-bugs claims to be a working, oily taskmaster.

FROM OVER THE HORIZON comes the unmistakable grunt of a muffed piston engine: husky, flat, muted—a cross between maybe a D Jag and a small diesel Cat. What next heaves into view looks like a streamlined Dresden China gravy boat with skids and a rotor mast – the Enstrom F-28A.

The auditory signature all the way down final to hover and squatdown is strangely unhelicopter, since the characteristic hum, whine and drone seem to be largely missing.

If the pilot keeps the rotor revved up, you may approach under the nine-foot-high sweep of those palm whackers without a qualm and unlatch the out sized contact lens employed as a door. Inside: no stingy little leatherette Eames chairs, but an upholstered woolen bench cushion stretching clear across the cockpit.

The inside is faintly Art Nouveaux and Macy’s Modern, gleaming with nickel-plate from rudder pedals to control sticks and heel scuff plates, while carpet and rear headliner glow in Moulin Rouge, and every Plexiglas surface comes framed in delicate, wand-like mullions and eggshell plastic.

The whole thing looks more like a blue-ribbon industrial designer’s exercise than a working, oily helicopter. But pile into the Enstrom F-28A, loop your leg over the cyclic and strap in. Then flap your elbows in a vacant pool of extra airspace and grab onto that fat, fighter-grip cyclic stick.

It even has a trim button, of all things—a “Chinese cap,” corrects Jerry Smith, (regional sales manager for Enstrom at White Plains, New York). For hover, trim comes full back and to the left. “You fly this helicopter with the trim,” stresses Smith. “Otherwise, the controls will seem stiff.”

If you’ve flown the older, earlier F-28 (sans “A”), you are mentally prepared to build forearm muscle as you attempt to work a collective and cyclic that react as though jointed to the controls with stiff leather thongs. But aha, not so today. What could be criticized earlier as stiffness might now be more correctly assessed as merely “solid feel,” and not unpleasant.

Fore and aft, side to side, there is a nice harmony (that includes the rudder pedals) throughout the hovering exercises. Squeeze in a little friction, and you may release the collective with your left hand and maintain a decent hover in the Enstrom F-28A, provided you don’t stir the cyclic excessively.

Keep the rotor RPM in the green, however, because there’s a chunk of inertia overhead, and once you lug down, it is difficult to regain rotor speed without easing off on the collective bite. Now try a hovering autorotation. Twist off the power, but lead a bit with right rudder or she’ll snap left—settle and touch down.

Rate the reaction “average” for this size rotorcraft. Next, hold on while Smith slams the Enstrom F-28A cyclic around, twanking and thunking the poor craft on its oleo-mounted skids to demonstrate its apparent immunity to ground-resonance problems.

Then lift her up and pull away for a normal takeoff. Smith reminds: push in trim, forward and to the right. If you forget, however, the stick pressures are mild, and not unlike those of a fixed-wing airplane that needs a bit of trimming.

In cruise, the Enstrom F-28A will sock right up to a creditable 100 mph (Vne is 112 mph). For once, the pilot may let go of the cyclic with impunity, to fiddle with charts, radios or whatever, and he can rest assured that disaster will not strike. And mind you, this little bonus comes without the extra mechanical and financial encumbrance of an artificial stabilization system.

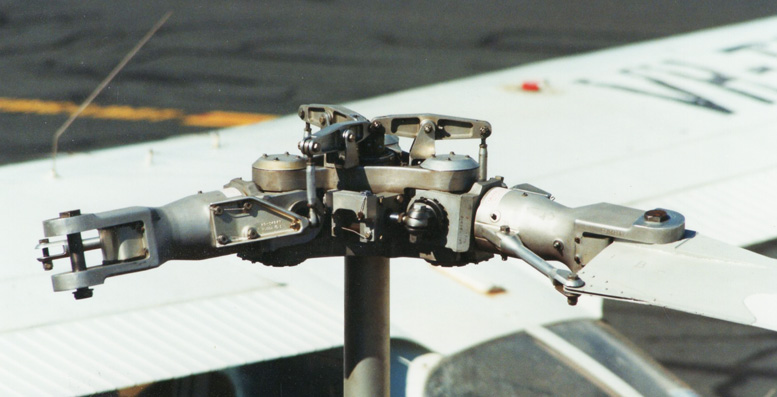

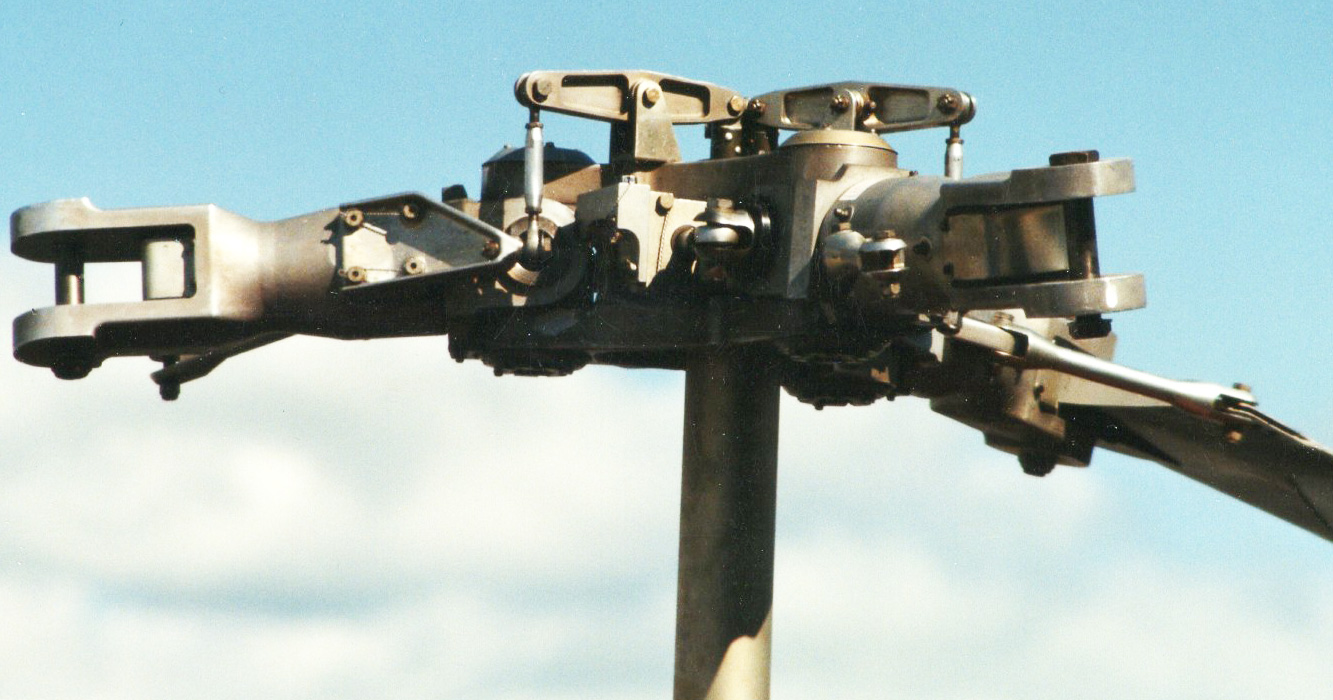

This is because of the Enstrom’s unique Lamiflex thrust bearing design in the main rotor head, which tends to exert a centering force on the rotor system. This hands-off stability characteristic does not extend to hovering, though, since the aircraft tends to nose over if you release the cyclic.

What’s this gracefully streamlined vessel like at high cruise speeds? The aircraft we flew generated a definite thumping rotor beat, but Smith attributed it to a correctable blade-tracking peculiarity not common to others of the F-28A genre.

The interior: Art Nouveau with nickel-plate controls and a flat instrument panel, of all things.

Engine noise in cruise, however, is muted quite decently, and the sound level in the cockpit is probably a bit better than average. Look overhead at the rotor mast during cruise, and you’ll be surprised to see how slowly it seems to be turning. That’s because it rotates at only 330 rpm, compared with up to 530 rpm for the Hughes 269, for example.

As for maneuvering, bend in some lateral pressure on the Enstrom F-28A stick for a turn, and you feel a definite, but not really awkward, resistance. With three aboard, the F-28A cockpit is a bit like the three-abreast seating on a commuter train: snug, but tolerable for short flights.

With a trio of 170-pounders on board and full fuel (30 gallons), the ship is actually slightly over gross, but you can probably get away with a couple of attache cases in the rear baggage compartment—which, by the way, has a generous 60-pound limit, but comes as optional for another $400.

Autorotations in the Enstrom are fairly pleasant events, since the approach angle is rather less steep and precipitous than in, say, a Hughes or Brantly. Sixty mph is the accepted autorotation speed, and the height/velocity curve allows a generous 30-mph minimum airspeed for a safe power-off takedown in the event of engine failure.

During a normal approach, the bird tends to be a wee bit slippery, and you counter a tendency to autorotate by slowing down a bit early and keeping the blades loaded with power on. The Enstrom has several competitors in the three-place rotorcraft market: the Hughes 300 and a trio of Bell 47Gs with different engine setups.

The Enstrom shows up well among them in terms of speed, with 20 mph over the Hughes and from 16 to 19 mph over the Bells. With a full fuel load, however, the Bells will lug an extra 200 to 300 pounds of payload (though you may have to carry it on your lap or strapped out in the breeze, since there’s no baggage compartment, per-se).

The Hughes carries roughly the same payload as the Enstrom: three guys and little else. The Bells are priced from $4,000 to $12,000 higher than the Enstrom F-28A at $37,950 basic; the Hughes goes for about $1,000 less, at last report.

Enstrom is, however, counting on improving its competitive position further in the future by bringing out a turbine-powered model, the T-28, with a 240-hp Garrett-AiResearch engine and a whomping useful load nearly double that of the present piston model. It will have a price tag of around $62,000 (1969 price).

They’ll also be introducing a 225-hp turbocharged piston model. Both are due for certification about the first of next year. Furthermore, the entire Enstrom position is buttressed with extra security and momentum, thanks to the benevolent paternal custody of the big Purex Corporation, a marriage consummated last fall.

The F-28A, then, has its fair share of attributes in the chopper arena: good speed, looks and hands-off cruise stability. It generates an inoffensive amount of racket, and it has a nice height/velocity envelope. It lacks a rotor brake, extra payload with three aboard and just a couple more inches of shoulder room.

But don’t go away; science marches on.

No birdcage tail truss for the Enstrom – instead, a Fiberglass and aluminum cocoon. Result: a 100-mph cruise on 205 hp.

| Enstrom F-28A HelicopterSpecifications | |

|---|---|

| Price (1969) | Base price $37,950 |

| Engine | Lycoming HIO 360 C1B, 205 hp |

| Rotor diameter | 32 ft. |

| Fuselage length | 28 ft. 1 in. |

| Height | 9 ft. |

| Disc area | 804 sq. ft. |

| Passenger and crew | 3 |

| Empty weight | 1,450 lbs. |

| Useful load | 700 lbs. |

| Gross weight | 2,150 lbs. |

| Fuel capacity | 30 gals. |

| Oil capacity | 8 qts. |

| Baggage capacity | 6 0 lbs. |

Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Performance |

|

| Rate of climb | 950 fpm |

| Service ceiling | 12,000 ft. |

| Hovering ceiling IGE | 4,900 ft. |

| Maximum speed (Vne) | 112 mph |

| Cruise speed (75 % power) | 100 mph |

| Range (at 75% power cruise) | 200 mi. |

Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Flight characteristics |

|

| Control response | Solid |

| Hands off stability | Yeah |

| Autorotations | Good |

| Hovering | Good |

Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Pilot Utility |

|

| Visibility | Good |

| Seat adjustment & comfort | Pleasant |

| Accessibility of switches, etc. | Good |

| Panel layout | Nice |

Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Cabin comfort |

|

| Entry-exit ease | Good |

| Ventilation | Average |

| Noise level | Not bad |

Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Maintenance access |

|

| Engine | Good |

Enstrom F-28A Helicopter Quality |

|

| Interior and exterior finish | Handsome |

SERIA INTERESANTE CONOCER LAS EXPERIENCIAS DE PILOTOS INSTRUCTORES DE LOS DIFERENTES MODELOS ENSTROM, DEBILIDAFES Y FORTALEZAS DE SUS MODELOS RECIPROCO Y DE TURBINA, SI SABEN DE ALGUN LINK DONDE PUEDA OBTENER ESAS LECCIONES APRENDIDAS, DEJENME SABER POR FAVOR.

IT WOULD BE INTERESTING TO KNOW THE EXPERIENCES OF INSTRUCTION PILOTS OF THE DIFFERENT ENSTROM MODELS, THE WEAKNESSES AND THE STRENGTHS OF THEIR RECIPROCAL AND TURBINE MODELS, IF THEY KNOW OF ANY LINK WHERE YOU CAN GET THESE LESSONS PLEASE LEARN.