Most Popular Piston Helicopter Manufacturer

ARTICLE DATE: August 1989

With over 1000 flying and a four-place under construction, Robinson Helicopters is firmly established as the major manufacturer that dominates the piston helicopter field

It wasn’t too long ago that the prospective helicopter pilot — or, for that matter, the prospective owner of a light helicopter — faced choices that were both few and hard.

As the fleet of existing piston trainer helicopters — preponderantly Bell 47s of various vintages and models — grew older, it became increasingly difficult to operate and maintain. New piston helicopters were still being manufactured by Hughes and Enstrom, but they were exceedingly expensive and often not much less expensive to operate.

Moreover, even if you could find one in which to learn to fly (and there were a few successful operators, such as Helicopters Unlimited in the San Francisco area), you were often faced with an inability to get insurance.

Those with big bucks could, of course, buy something like a Bell JetRanger or Hughes 500, starting on the wrong side of $300,000, and when you’re in that league a few more tens of thousands to places like FlightSafety International and your friendly neighborhood insurance guy wouldn’t make much of a dent — but for the rest of us, getting a helicopter rating, much less a helicopter, was a pretty tough row to hoe.

Enter, at this point, one Frank Robinson. No stranger to helicopters, in fact, he started with Cessna when they developed their Skyhook, the first light helicopter to receive IFR certification.

Later he moved to Kaman, then to Bell, and finished working for someone else as an engineer at Hughes, where the product line included both the workhorse Hughes 500 turbine (known to the Army as an OH-6 and to troops in the field as a Loach, for Light Observation Helicopter) and the little Hughes 300 reciprocal, known in an earlier version to the Army as the TH-55 and to the students and instructors who trained in it by a number of names, none repeatable on this family website.

At the time, the Hughes 300 was the smallest and lightest piston helicopter in production (the Brantly B-2 having ceased production some years earlier); even so, its price was starting to push the magic $100,000 figure, and Frank figured there might be better and less expensive ways to go about a light helicopter project. (I defy you to find me an aeronautical engineer working for a big company who doesn’t dream of building his own project someday.)

Frank was also learning more than just the right and wrong ways to build a helicopter during his years at Hughes; he’d already been exposed to large-scale production lines at Cessna, and it must have been evident to him that one of the ways Hughes managed to control costs on helicopters (to the extent that did, at any rate) was to have access to extensive fabrication and small parts manufacturing facilities.

Let us not forget, Gentle Reader, that the outfit was once called the Hughes TOOL company . . . Accordingly, Frank Robinson designed the aircraft that would become, with remarkably few changes, the R22.

Judging both from the design itself and its subsequent success, with over 1000 built by the beginning of 1989, he took Geoffrey de Havilland’s famous advice to heart: Simplify and build in lightness.

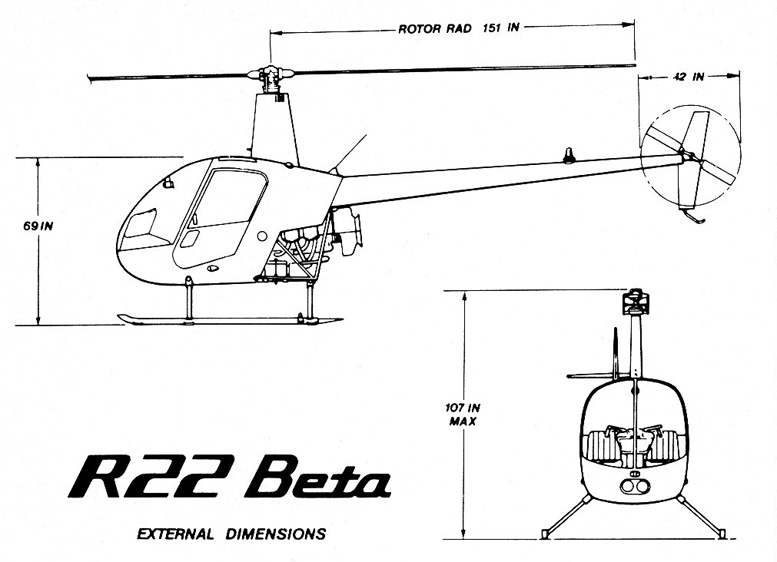

The R22 is not only very simple from both structural and mechanical viewpoints, it’s also very light, weighing in at only 826 lbs fully equipped.

Useful load of the current version isn’t all that much less than its empty weight at 544 lbs; even with full standard and optional auxiliary fuel, for a total of 30 gallons, the little ship will still carry two 200-pounders with enough left over for minimal baggage.

Surprisingly good performance goes hand in hand with this light weight — surprising only in view of the R22’s modest power. In a sense, it starts with light weight; this allows you to install a relatively low-powered engine, which in turn weighs less than a bigger one, etc.

When the ship first appeared, transmission limitations called for its 150-hp Lycoming 0-320 to be derated to 123 hp, allowing it to maintain maximum permissible power to higher altitudes.

In the current Beta version, overall power has been raised to 160 hp and permissible takeoff power has been increased 131 hp, still well below the limits of the rugged carburetor engine (of course, a carburetor is also lighter and cheaper and gravity feed from the fuel tank obviates the need for fuel pumps).

A trip through the Robinson factory at the Torrance, California, airport is quite impressive for several reasons. Given the small size of the company compared to aerospace giants, there’s a remarkable investment in numerically controlled equipment, allowing Robinson to fabricate many of the parts that would normally be farmed out to subcontractors.

Advances in tooling also allow many parts to be machined from already heat-treated stock, rather than having to heat-treat them after machining: this results in considerable cost reductions Frank Robinson told me that even though-parts are being made to better and better tolerances, rejection rates still run around 10 percent: he thinks that his inspectors feel compelled to reject about that many parts to justify their employment!

Equally impressive is the feverish pitch of activity. At present, the firm is turning out six new helicopters every five working days; in addition, about one and a half used ships are completely rebuilt each week.

The rebuild program is a very popular one among Robinson operators; at TBO (2000 hours for both the engine and all life-limited parts on the helicopter) the entire aircraft is returned to the factory, disassembled to its component parts, and sent down the assembly line right along with the brand-new birds.

Robinson also maintains an active training program, not for the public at large, but specifically for Robinson operators. The three and a half day course is aimed specifically at CFIs but is open to any Robinson pilot, and one hears all sorts of accents around the class area; some 80 percent of sales are exports.

By maintaining tight control over pilots as well as the aircraft, Robinson is able to offer operators very low hull and liability insurance rates. Interestingly, the firm carries no product liability insurance, another way in which cost of the helicopters is held down.

As Frank puts it, anyone who brings a big lawsuit against us had better be ready to become a helicopter manufacturer if he wins. Thus far, this system has worked exceptionally well.

Production and development test pilot Paul Parszik — who’s been at Robinson for a third of his 30 years — was my mentor in an R22 refresher, and I must confess that I was a bit apprehensive before we got underway.

Not because of the helicopter, or because of Paul, who’s one of the better instructors I’ve been with over the years; rather, because it had been quite a while since I’d been in a light helicopter, and although I learned to fly choppers in a Brantly, most of my subsequent several hundred hours had been in larger turbine equipment.

It’s more of a truism in helicopters than in almost any other type of aircraft that the bigger they are, the easier they are to fly; moreover, I find that at least for me helicopters are the single aircraft type in which I get rustier, faster, if I don’t have a chance to fly as often as I should.

To make matters worse, Robinsons have a reputation — founded apparently entirely on the testimony of those who’ve never flown one — for being twitchy. Paul worked me through a thorough prefiight, made easier by the fact that just about everything you need to inspect — and that’s plenty even on a helicopter as simple as the Robinson — is easy to get at.

Despite this, the Robinson has little of the angular mosquito-carrying-a-flushlight-bulb appearance of some other light helicopters; the cabin and tailboom are smoothly faired, and the tall rotor mast (which improves both ground clearance and stability) is housed in an aerodynamic fairing.

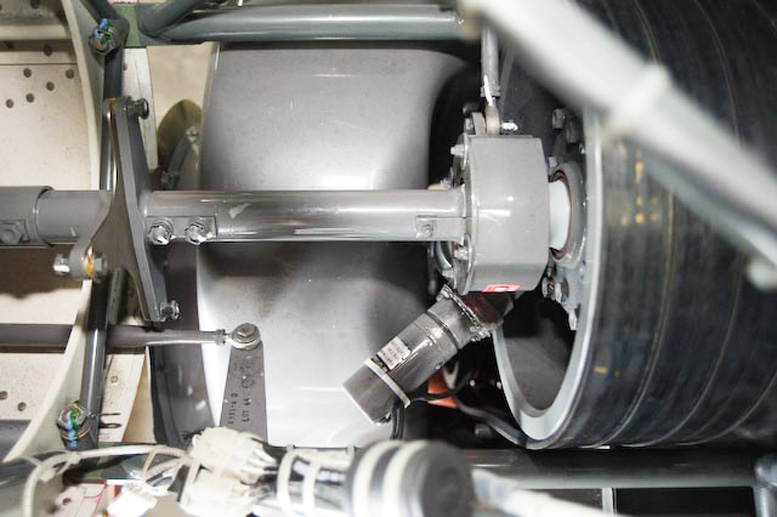

Unlike most other helicopters, the R22 has no grease fittings, making it the first reciprocal helicopter I’ve flown in which a red shop rag isn’t a required part of the pilot’s attire; according to Robinson, no maintenance (other than required preflight items, of course) is required between 100-hour inspections.

Despite the ship’s overall petite size and dainty appearance, there’s plenty of room in the cockpit, and a couple of briefcase-size suitcases can go under the seats. The instrument pedestal between the seats offers room for attitude and directional gyros as well as the usual dual tachometer, manifold pressure gauge, airspeed, altimeter, and VSI; engine gauges and radios are on the center pedestal.

A larger instrument panel is also available; although the R22 is not licensed for IFR flight as such, it’s become a very popular instrument trainer, and in that role it’s outfitted with HSI and full IFR radio package.

One unique way in which Robinson saves on space is the arrangement of the cyclic stick: Instead of one for each pilot, it comes up between the seats and is crowned by a pivoted T-bar at the top with a stick grip at each end. This makes it a lot easier to get in and out and keeps the controls out of the way of the non-flying pilot: When you have the stick grip pulled down to a comfortable flying position on your side (ie, with your hand resting on your thigh so you can fly with gentle finger pressure), it’s raised a few inches on the other side.

Robinson instructors get used to flying with a raised hand, I suppose. The left (passenger) side of the T-bar, and the pedals on that side, can be removed in a few moments.

The little Lycoming lit off with a twist of the key, and a simple flip of a panel switch started the automatic clutch engagement process. After a few moments warmup I ran through the usual pre-takeoff checks, including cutting the throttle to split the needles and verify that the overrunning clutch disengaged properly.

The Robinson tachometer is another unique item; where most other helicopters have mechanical tachometers with dual needles working around a central pivot, the Robinson uses an electronic tachometer with needles coming in from each side of the case.

It sounds strange; in fact, it must appear fairly natural, since I didn’t even notice that it was different once we got underway. Paul lifted us off from the crowded ramp in front of the Robinson flight test and delivery hangar, hovered over to a grass area, and turned the ship over to me.

Although my first tendency was to overcontrol, I think I’d ascribe that more to my own rustiness than to any inherent twitchiness of the Robinson. In fact, the only control with which I had any difficulties was yaw; my first pedal turns, in a somewhat gusty 15-knot wind, weren’t nearly as smooth as I’d have liked.

A little cautious experimentation laid at least part of the blame on the Vibram soles of my size 10 natural-dung Fryes, which were binding on the pedals; after setting down, climbing out, and stashing the offending footgear under my seat I spent the rest of our session flying in my socks, and things got much smoother.

After a little hover practice and some liftoffs and touchdowns we left the airport traffic area and headed off on a brief scenic tour around the Palos Verdes peninsula. This also offered a chance to run through one of the best coordination exercises for helicopters, accelerating and decelerating while maintaining a given heading and altitude.

Because of Torrance Airport’s neighborhood of wealthy noise-sensitive neighbors, we elected to shoot practice approaches and landings to a small barge lying at anchor in the harbor at San Pedro.

The wind was considerably stronger out over the water, but the R22 handled the gusts with aplomb. Coming to a hover even after a fast, steep descent didn’t come near the helicopter’s power or control limits, and it was gratifying to feel at least some of my old chops coming back.

Autorotations were next on the menu, executed over a harborside area where serried ranks of imported cars are stored to maximize dust and salt corrosion while dealers wait for more

favorable exchange rates.

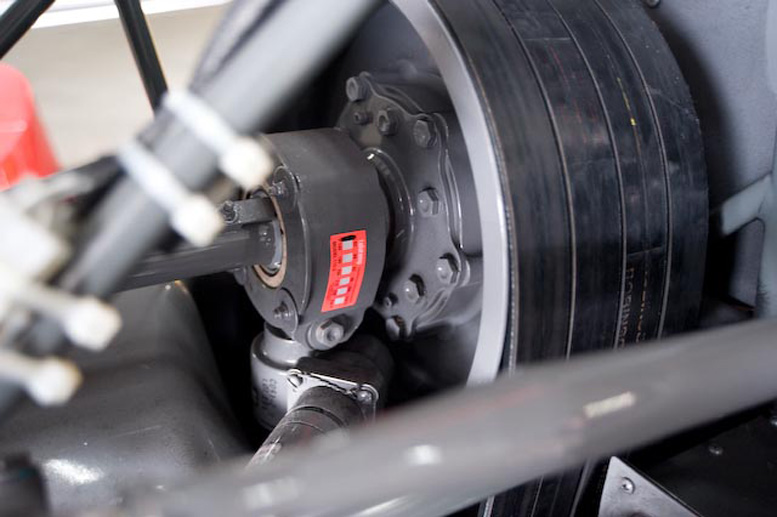

This is another area where non-Robinson pilots are quick to point out the dangers of a light rotor system; in fact, the R22’s unique triple-hinge semi-teetering main rotor has tip weights, sheds almost no rpm as power is cut, and builds up turns very impressively in the flare.

A couple of years ago, I had the chance to go through Robinson’s instructor safety course in an earlier version of the ship, and found it impressive that the factory instructors checked everyone out in full autorotations to touchdown, including from 180-degree turns, as a matter of course.

We returned to the airport for some pattern work; because of its heavy fixed-wing traffic, Torrance’s helicopter pattern is so small (about four city blocks) that only one helicopter is allowed to work in it at a time.

Approaches to the pad in a quartering crosswind were no problem, and just as well, since missing the pad would be messy: The north side of Torrance, right up to and around the pad, is a thriving strawberry farm, and the berries just beneath our skids were red, ripe, and obviously squashy. As we took the ship back to the test hangar pad and shut down, Paul mentioned that he’d recently returned from a stint flying a float-equipped R22 Mariner off a tuna clipper off Venezuela.

More and more of the ships are being operated as fish spotters; the float installation adds only 32 lbs to the basic weight, and the only other airframe changes are a slightly higher tailboom angle to keep the tail rotor away from the water and a larger vertical fin with an endplate.

The Mariner version brings the number of available R22 models to four: The basic helicopter, the instrument trainer, the Mariner, and a police version featuring additional lower windows and various options such as loudspeakers, searchlights and, for all I know by now, napalm racks for those inner-city patrols.

The police ship is finding acceptance due partly to its low cost and partly because the ship is fairly quiet. Of course, the major development at Robinson now that the R22 series is doing so well is that of the four-place R44.

After all these years of apparently doing everything right, Frank knows better than to mess with a good thing, and while the prototype I saw is in the earliest stages of construction, it was obvious even before seeing a three-view drawing that it’ll look very much like a bigger R22.

Power will be a 260-hp Lycoming; if anything, the new ship will look even sleeker than the R22, since its engine will be enclosed rather than exposed.

By now, of course, even a new Robinson R22 costs close to $100,000; by the time you hang a few options on it, it’ll go out the door with a six-figure price tag. On the other hand, its competitors cost considerably more, and, after all, we’ve advanced to a golden age in which even a four-place fixed-gear fixed-wing single(!) can cost that much.

A helicopter will never be the flying machine for everyone, of course, and Frank Robinson probably knows that more than most — but for someone making trips of no more than, say, 300 nm, an R22, with its 100-mph cruise speed, still probably offers the fastest economical door-to-door transportation.

In addition, helicopters are the last bastion of true eyeballs-out seat-of-the-pants flying, and that, as well as their magic carpet abilities to go anywhere, can provide the lucky pilot with rewards more than worth the price.

Almost every pilot, whether he or she admits it or not, is fascinated by helicopters.

There’s good reason for that; not only can these weird and wonderful machines stand still or even back up in midair, but they’re unique in their ability to operate in and out of places absolutely unattainable (or at least unattainable more than once!) by fixed-wing aircraft.

On the other hand, many pilots automatically assume that a helicopter is at least as unattainable for them as the places some of them land.

There’s no question that helicopters have proliferated steadily since they first were really accepted during the Korean War (see the opening title of M*A*S*H); on the other hand, they also seem to have become steadily larger, more capable, more complex, and vastly more expensive and beyond the means of the average pilot.

Moreover, they labor under the onus of maintenance hogs — two hours in the shop for every one in the air. In fact, this is no longer the case. True, turbine helicopters are insanely expensive; true, older piston helicopters, like the Bell 47s that open M*A*S*H and that kept my generation glued to the tube watching Whirlybirds did indeed require a great deal of maintenance.

Modern light piston helicopters, though, have evolved to be both relatively affordable and considerably more reliable and robust than their predecessors of the 1950s.

In these articles, we take a look at two excellent products that encompass the two ends of the light piston helicopter spectrum: The Robinson R22 Beta, a certificated production helicopter that’s gained widespread acceptance both in the US and abroad, and the RotorWay Exec, a similarly performing homebuilt kit — that’s right, a homebuilt! — that occupies a different niche, but in just about as many countries.

Be the first to comment on "Robinson Piston Helicopter Manufacturer"