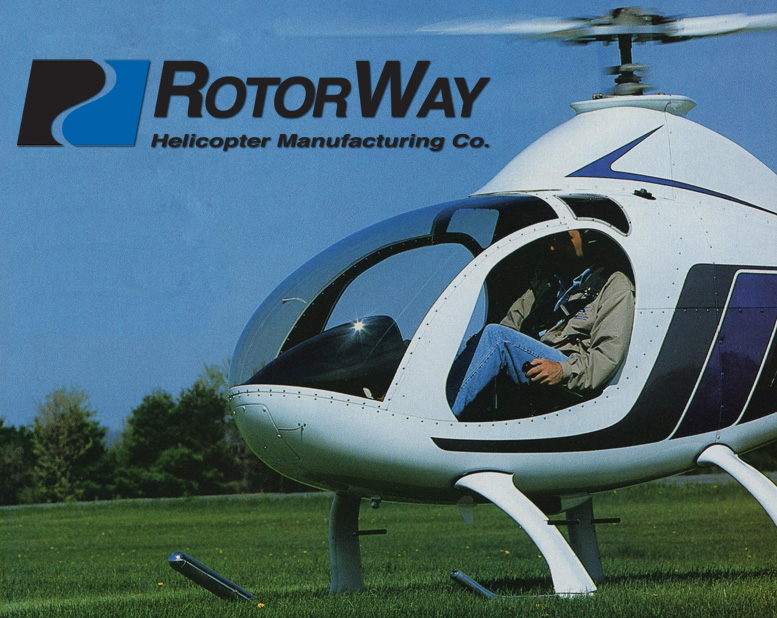

Classic RotorWay Exec 90 Helicopter

Ed DeRossi says he likes a challenge.

COURTESY: EAA Sport Aviation July 2002

That may be an understatement. With a lifelong passion for helicopters, he was among the first to build and fly radio control (RC) helicopter models—no small challenge. Then he built a RotorWay Exec 90 kit helicopter, finishing it in 1994 and earning Reserve Grand Champion Rotorcraft at EAA Oshkosh in 1995 and Grand Champion in 1996.

Today, Ed is EAA AirVenture Oshkosh’s chief rotorcraft judge. He demonstrates his Exec 90 Kit Helicopter at local air shows, and he travels around the world helping others to complete and fly their RotorWay helicopter kits.

He probably knows more about RotorWay helicopters than anyone else outside of RotorWay International. Ed’s interest in flying machines ignited at 5 years old when his father, an RC enthusiast, got him started building simple flying models.

Five years later he was building and flying RC airplanes, and when RC helicopters came on the market in the early 1970s, Ed was among the first to build and fly one. “I’d always wanted to fly, especially helicopters,” DeRossi says.

“I flew model helicopters because I didn’t think I’d ever be able to afford a real one. There were no kit-built or homebuilt helicopters then, just factory-built helicopters. All the kits and homebuilts were gyrocopters, and I wanted to hover.”

DeRossi logged an hour of dual instruction in a Robinson R-22 — “just enough to learn to hover” — and considered joining the Army National Guard. “But they couldn’t guarantee me that I’d be able to fly helicopters, so I gave up on that.” He continued to fly RC helicopters and dream.

In 1967, B.J. Schramm, homebuilt helicopter designer and founder of RotorWay, introduced his kit helicopter — the Scorpion helicopter. RotorWay’s company history says the Scorpion helicopter was “the first real kit helicopter on the market that actually flew.” Underpowered, the Scorpion helicopter suffered its share of teething problems, like any new design.

Using the Scorpion’s lessons, in 1980 Schramm introduced a new two-place kit helicopter, the RotorWay Exec 90 Kit Helicopter. Inevitably, the kit caught Ed DeRossi’s attention, and for 10 years he studied it every year at EAA Oshkosh and Sun ‘n Fun.

After high school DeRossi went to work as an automobile and truck mechanic for Goodyear. After a few years there, he worked for 10 years at motorcycle shop, repairing and maintaining bikes and snowmobiles.

Then he opened his own auto repair shop. He continued to fly RC models (a hobby he still pursues). With a passion to fly, but little time and money for flying full-sized airplanes, he bought an ultralight—a 15-hp weight-shift Quicksilver.

Birthday Building Project – Exec 90 Kit Helicopter

Through the 1980s, Ed was a dealer for Cobra and King Cobra ultralights. He ran a sky diving school for a few years and earned his fixed-wing private pilot certificate in 1988. Still, every time he went to EAA Oshkosh or Sun ‘n Fun, the RotorWay Exec helicopter beckoned to him.

“When my 40th birthday rolled around,” DeRossi says, “I said to myself, I’ve got to do this. I went to Oshkosh and put down the deposit on an Exec 90 kit helicopter as a present to myself on my 40th birthday, July 27, 1993.”

While waiting for his Exec 90 Kit Helicopter to arrive, Ed sold his ultralight dealership and took a full-time job as a mechanic for the local power company. That would give him the time, money, and freedom to work on his RotorWay helicopter.

It arrived in September 1993, and over the winter Ed worked on it like a man on a mission. He still had the building that had housed his auto repair business, and it was perfect for building the Exec 90 helicopter. “I had the shop and most of the tools, and whatever else I needed, I bought as I went along.”

DeRossi ready for takeoff.

His years of experience as a mechanic helped Ed complete his Exec helicopter in near-record time, and he also credits the kit’s design and the people at RotorWay. The company’s builder support is excellent, he says. Tom Smith was his main RotorWay contact, and “I probably called Tom a dozen times with questions, and he was right there with the answers.”

“The whole company was really great.” Working the night shift at the power company garage left Ed’s days free for building and flying. He’d come home from work and spend every available minute on the project.

“I didn’t get a lot of sleep that winter,” he adds, “but I wanted to get it done.” “I only took time off for two things,” Ed says.

“A week at Sun ‘n Fun, and to snow blow the apron outside the shop. When I finished the project, I wanted to be able to hover it, so I kept the apron clear of snow.” Every other spare moment was spent on the kit.

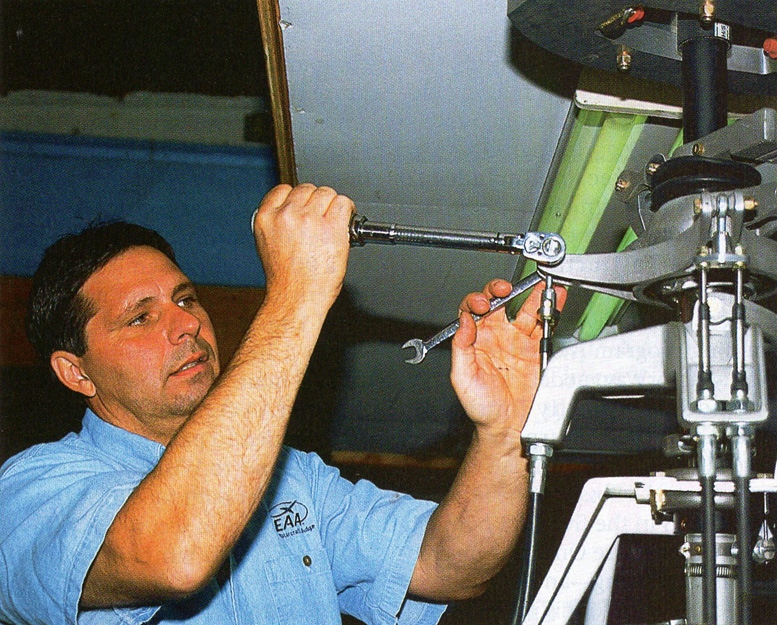

By June of 1994, just nine months after the kit arrived, Ed had put more than 1,000 hours into the project, doing all of the work himself, except the chrome plating. His Exec 90 Kit Helicopter was ready for its first hover test, and he rolled it out of the shop. “As it turned out, that first day, I didn’t hover it,” he says.

“I started it up and spun the rotors, but it just didn’t feel quite right.” Ed may have been in a hurry to finish the kit and fly it, but he wanted it done properly. That was part of the challenge. He pulled the ship back into the shop and checked everything one more time.

DeRossi working on his Exec’s rotor head.

The next morning, he rolled it out again, started the engine, and lifted the ship into a hover. “It worked just the way it was supposed to.” Challenge met. Mission accomplished. It was time to set the project aside and head for Tempe, Arizona, for Phase One of RotorWay’s factory flight school.

Because many of its customers are new to helicopters, RotorWay began training its customers in the 1970s, when it introduced the two-place Scorpion II helicopter kit. For students like Ed, who are certificated fixed-wing pilots, the FAA requires a minimum of 15 hours of dual instruction and 15 hours of solo flight to earn a rotorcraft rating.

All students in the RotorWay helicopter program must have at least a third-class medical certificate and a student or private pilot certificate. RotorWay divides its training program into three phases. Exec 90 Kit Helicopter Phase One reviews building, rigging, and maintaining the Exec and includes 10 hours of dual instruction.

Phase Two consists of more ground school, more dual instruction, and cross-country flights. Phase Three concludes with the FAA checkride. The training program is open to owners of any RotorWay model.

Students typically finish each phase and then return to Arizona several weeks or months later for the next phase. DeRossi finished the first two phases in the five days normally allotted for Phase One, and he credits his fixed-wing — and RC helicopter — experience for his progress.

Ed doesn’t like to brag about it, but RotorWay was impressed, and it named him 1994’s “RotorWay Student of the Year,” and he gives a lot of credit to the Exec 90 helicopter. “It’s a really stable helicopter,” he says. “It’s small compared to a Jet Ranger, and because it’s small you expect it to be kind of twitchy. But it’s not. The RotorWay helicopter is very stable and very pilot-friendly.”

Upon completing the first two phases of training, RotorWay gave Ed a 90-day endorsement for solo hovering and sent him home. His total time in helicopters at that point: 1 hour in a Robinson R-22 and 7.5 hours in a RotorWay Exec 90 Kit Helicopter.

With EAA Oshkosh a month away, Ed intended to pack up his Exec 90 and trailer it to Wisconsin. Starting with a trailer built for sprint cars, he added clamps to secure the skids to the deck and a winch to pull the Exec 90 Kit Helicopter up the trailer’s drop-down ramp.

Then he added one of the few custom touches to his helicopter, a special fitting for attaching the winch’s cable. It takes Ed about an hour to remove the main rotor blades, attach ground-handling wheels to the skids, winch the Exec onto the trailer, and clamp it out. (Reversing the process also takes an hour.)

DeRossi’s Rotorway Exec panel is simple but supremely functional and uncluttered.

To stabilize the Exec helicopter on the road Ed designed and built two tail boom supports using aluminum tubing with a motorcycle shock absorber on one end. The tubes fasten to fittings on the trailer wall or deck, and the shock absorber attaches, through a small spring, to the tail rotor.

The vertical support lifts the tail just enough to take the strain off the fuselage, and the shock absorber cushions bumps in the road. The horizontal support keeps the tail boom centered and from banging against the trailer’s walls, and the shock absorbs the bumps and vibrations.

At Oshkosh, RotorWay gave Ed another 90-day endorsement, allowing him to continue hovering his Exec 90 helicopter until he could return to Tempe for the third phase of training and his FAA checkride. At that point, he had 13 hours of hover time in the Exec. Ed earned his helicopter rating that fall and put the finishing touches on his project over the winter.

He returned to Oshkosh in 1995, where the judges named his Exec 90 helicopter Reserve Grand Champion Rotorcraft. After receiving the award Ed learned from one of the judges that he’d missed the top spot by just a few points and that a better interior probably would have earned him the top award.

“I told him I didn’t build a fancy interior because I wanted it light and functional,” Ed explains. “I told him it was the best interior I could build with the materials I had; it’s not fancy, but it was done with precision.”

DeRossi returned to Oshkosh in 1996, and that year the judges named his Exec 90 the Grand Champion Rotorcraft. “I didn’t change anything,” Ed says. “And in 1996, the same judge told me mine was the nicest RotorWay he’d ever seen. I think the second year, he looked more closely at the details and the finish.”

EXEC 90 KIT HELICOPTER – JUDGE ME

Bob Reece has been involved in aircraft judging since the 1970s and has directed the judging at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh for the last 10 years. Most of the more than 160 EAA AirVenture judges are experienced homebuilders and/or restorers, but, he says, this isn’t a firm prerequisite.

In-depth knowledge of aircraft systems and materials is important, he says. Bob stresses that being an aircraft judge is “a big commitment.” Judges are volunteers who must attend the convention from start to finish and agree to be at EAA AirVenture for several years running.

Judge candidates undergo an intensive interview and screening process, and new judges are chosen carefully. It takes “two to three years to get a judge trained well enough to where I can confidently send him out on his own—if I have to—and he can judge any homebuilt on that field.”

They have to be. says Reece. because “if you get an award at Oshkosh, that’s the epitome of judging.” Judges examine 10 categories on each homebuilt aircraft, awarding up to 10 points in each one. Each category has equal weight in the cumulative score.

“It’s up to each judge to apply his or her expertise in looking and probing and whatever,” Reece explains. “I don’t expect three judges to go out there and look at that airplane and all come back with the same score.”

To be eligible for an EAA AirVenture award, at least three judges must examine an aircraft. Reece sends his homebuilt judges out in groups of three, with each group starting in a different area. Over the week, the groups will criss-cross, and more than three judges will look at most aircraft.

The more judges who look at an aircraft, the more accurate and objective the judging becomes, Reece says, but many airplanes don’t stay the whole week. Some fly in for a few days, or a few hours—long enough for three judges to look at the aircraft—and then fly out.

Each airplane is judged on its own merits. “We don’t judge this airplane against that airplane,” says Reece. “It may look like that’s what happens, but it doesn’t.” Judging is subjective, “but we make it objective by having an open point scoring system” and by using multiple judges who have been carefully selected and trained.

“We have judges who have been working with us for 20 or 30 years,” says Reece, and collectively, they possess a huge body of expertise. “They know how important the judging is and how meaningful the results are,” Reece adds. “They work very hard, they take it very seriously, and they are all very dedicated to doing it right.”

Rotorcraft judge

After earning the top honor in 1996 with his Exec 90 Kit Helicopter, DeRossi was recruited as a rotorcraft judge. All EAA aircraft judges are volunteers.

Carefully chosen, they serve as apprentices to the veteran judges for two or three years before going “solo.” All the rotorcraft judges are devoted to rotating-wing machines, and Ed and his three other judges arrive in Oshkosh early each year, to see what’s there before the crowds arrive.

If they discover a new kit, prototype, or one-of-a-kind design, they’ll spend time studying it before the judging begins. To determine the championship rotorcraft the judges “start by looking at its overall appearance from a distance—about 150 feet away,” says DeRossi. Then they move in for closer scrutiny.

They divide each ship into sections—cockpit, engine, tail boom, and so on — and examine each in detail, looking for evidence of the time, detailing, and workmanship that the builder has put into the project. “The finish, the hardware, uniformity from one side to the other, paint job—all these are important,” DeRossi says.

“We also want to know how much of the project did the owner do himself.” All other things being equal, work performed by the owner will get higher marks. These days most people who have their aircraft judged have professionals paint their homebuilt.

“For the builder, it’s a dilemma, because a great paint job can cut both ways.” “If you hire out the painting, it looks great. If you do it yourself, and do a less-than-perfect job, it’s your own work but it doesn’t look as good.”

“[The judges] sometimes end up deducting points for a less-than-perfect paint job and giving back points because the owner did his own painting.” Occasionally, a builder tries to pass off professional work—work he has hired someone to do for him — as his own.

“When that happens, and it’s not often, it’s pretty easy to figure it out by talking with the owner,” DeRossi says. “If you’ve done the work, you know every inch of that aircraft.” An owner who didn’t do the work isn’t going to know the project as intimately.

During his five years as a judge, Ed says workmanship has been improving — “most of the time.” Personal touches he’s seen on the RotorWay Exec helicopters include electric clutches, instruments, fancy interiors, storage compartments, and paint schemes. “Each year, we see more detail in the paint jobs.”

With his helicopter finished and flying, DeRossi spends a lot of time helping others with their RotorWay projects. “After the FAA has signed off on it, but before its first flight, I’ll go out, look it over, and fly it for the first time.”

“I spend about two days with each owner, making sure the ship is safe and that it flies the same as any other RotorWay helicopter.” DeRossi has worked with nearly 50 Exec builders in the last two-and-a-half years, traveling all over the United States and to Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Africa.

RotorWay builders find him at EAA AirVenture or Sun ‘n Fun, through the RotorWay factory, or through informal builder networks. “I get phone calls every week from RotorWay owners,” he says. And the number of owners is growing steadily.

A hobbyist at heart. DeRossi’s Exec perched atop his R/C shop.

RotorWay sells 70 to 90 kits a year worldwide. RotorWay’s Susie Bell says Ed is “definitely one of our most knowledgeable customers.” From his experience as a builder and EAA judge, “he really knows his stuff.”

For Ed, sharing his knowledge and helping homebuilders like himself to achieve their dreams has been one of the unexpected rewards of building his own helicopter. Though he’s a regular at EAA AirVenture and at Sun ‘n Fun, DeRossi has never flown his Exec 90 Kit Helicopter to either gathering.

This year, as in the past, he’ll trailer it in from his home in Johnstown, New York. He only flies it in the summertime, and the farthest he’s ever flown the Exec 90 helicopter was just 160 miles, round trip.

“I like flying around home and landing where an airplane can’t,” he says. “I’ve flown to Wal-Mart and to lots of restaurants, landing in a corner of the parking lot or on the grass nearby.” He also flies to local events—including air shows. Last year Ed flew to the Schenectady air show, and the organizers asked him to be Saturday’s pre-air show act.

“I did some basic maneuvers—hovering, sideways and backwards flight, and a fly-by—just to show what a Exec 90 Kit Helicopter can do. With a skid I knocked over an orange rubber traffic cone—and set it back up.”

“Then I went up and did a couple of autorotations, each time landing right in front of the cone,” Ed says. “I didn’t want to bore anybody, so I kept the presentation short—about 15 minutes. Everybody liked it so much that they asked me to do it again as part of the regular air show on Sunday.”

He’s been invited back to the Schenectady air show in 2002, and he and his Exec 90 helicopter appeared at a local balloon festival in June. Most of the time, Ed says he flies his Exec 90 for the simple joy of it.

So far, he’s logged roughly 650 hours of good, clean fun. “There is an ice cream parlor near here, and I love to fly there.” He also mentions a favorite restaurant: “Whenever I land there for dinner, the owner gives me a free dessert.” Another unexpected reward.

Be the first to comment on "RotorWay Exec 90 Kit Helicopter"