Webb Scheutzow Helicopter Designer – Inventor

ARTICLE DATE: March 1974

EDITOR’S NOTE – “In 1961 Webb Scheutzow set out to fill what he saw as a gaping hole in the helicopter world . . . a low maintenance, easy to fly machine that could be marketed within a price range that would allow a significantly greater number of persons to own a helicopter. Today, Mr. Scheutzow is nearing completion of certification of one model and plans are well along for a version for homebuilders”.

“Beginning with this introductory article and continuing in future stories, the author will relate the history of his experimental work to date, detail the many technical innovations peculiar to his design and reveal his plans for rotary wing homebuilders”.

The helicopter is the only flying machine in history to rival and exceed the capabilities of wheeled or track-laying vehicles for point-to-point transportation. The helicopter leaps over mountains, streams, deserts, choked highways, flooded fields or burning forests with remarkable ease.

It can land or take off from a spot the size of its skid whether it’s level or not. It’s possible to fly in close proximity to power lines, up the mountain side, through the valley and across the plains at speeds of your own choosing. What else can do this… nothing else!

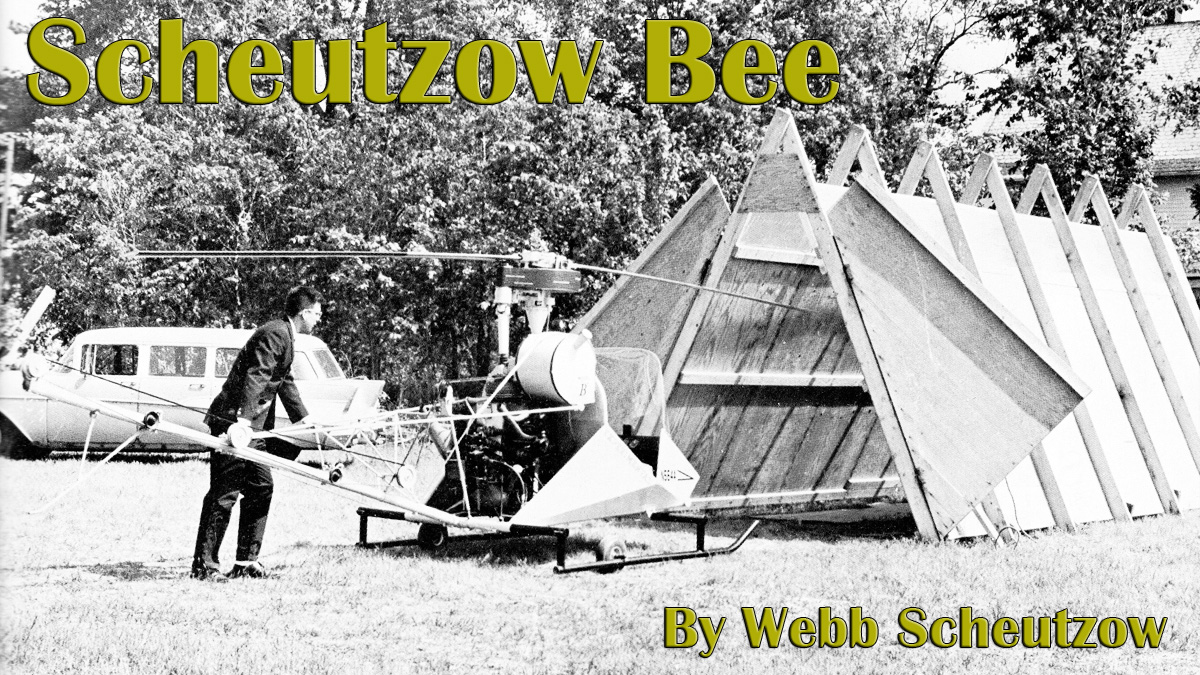

In the summer of 1961 the design of the BEE (or Model B) was started in the Scheutzow family garage-shop-office in Berea, Ohio. The objective was perfectly clear, but, as it would develop, the path could hardly be called smooth.

Paul Becka, (Left), Webb Scheutzow, (Center), and Jan Scheutzow May 1963 — at Strongsville Airport.

In the market place the Brantly B2 helicopter was just entering the production stage, the Hughes 269A was barely on the horizon, both of these priced around $25,000, the Bell 47 was selling for about $45,000.

If you will examine the function and components of even the simplest automobile side-by-side with the equivalent components of a small helicopter, it is immediately obvious that the helicopter is by far the simpler of the two.

Ten design areas to be thoroughly investigated in the next year were listed as follows:

-

Main Rotor Hub

-

Rotor Control

-

Main Drive

-

Main Rotor Blade

-

Clutch Components

-

Tail Rotor

-

Tail Rotor Drive

-

Fuselage & Cabin

-

Tail Boom

-

Landing Gear

Careful detail analysis of each item was made, many concepts investigated and sorted out, and layout drawings were made to fully investigate feasibility.

Principal design considerations, in addition to design simplification, were to make the helicopter easy to fly, design for infinite life components, use “fail-safe” designs eliminate items requiring costly tear down inspection, and replacement, design to eliminate rotor hub lubrication and fretting problems.

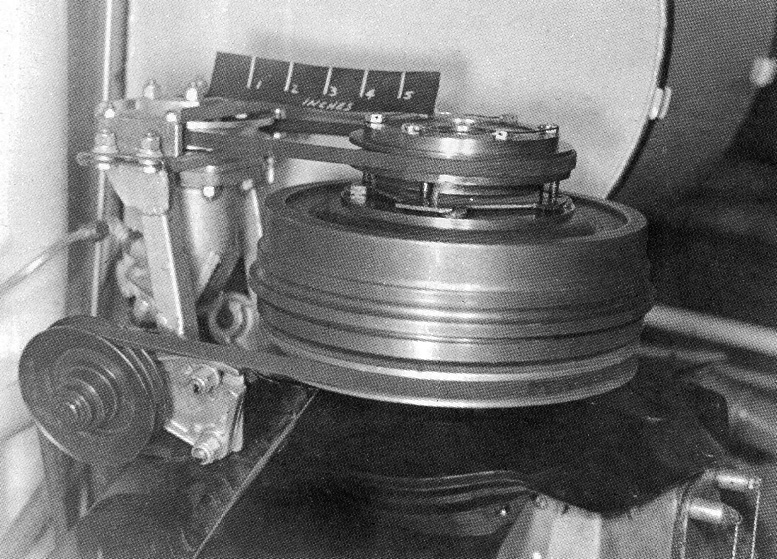

The end results of these efforts were later reflected in the Model B test bed pictured; N-564A. Design items 1, 2 and 3 were combined into a simple, rugged component, mounted on a static spring mast for vibration isolation.

The Scheutzow Model B helicopter on the Strongsville airport in the early 60’s. This was the first Scheutzow, but was called the Model B in deference to Henry Ford’s Model A. Webb also liked the concept of the “BEE” which flies from point to point to gather honey . . . the kind of utility all of us would like to have from our personal aircraft.

Rotor blades were mounted in a unique hub using elastomeric bushings in place of anti-friction bearings; V-belts which would fail safe replaced gears; and a new type of fail safe over-running clutch was devised.

N-564A was the first helicopter with an all elastomeric rotor hub to fly. It was airborne in a hover with Paul Becka, our A&E mechanic/pilot at the controls on January 9, 1963.

Back in 1963 I had stated our goals as follows:

“The helicopter is here to stay but only the availability of the small, inexpensive, low-maintenance-cost model is going to make it a universally accepted transportation tool. This is intended to be the ‘Cub’ of the helicopter world, with its ability to lift off and land in small areas where there is no airport. It will find its place in ranching, farming, or any job requiring travel or survey over a large area.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR . . . WEBB SCHEUTZOW

Webb Scheutzow, EAA 84561, had a ham radio ticket when he was thirteen. In 1939, while attending Case School of Applied Sciences, he couldn’t find summer work in Cleveland so he hitch-hiked out to California where the aircraft plants were beginning to hum . . . there was a war in the making.

His first job was at Douglas Aircraft, Santa Monica. There were about 3000 people employed by Douglas, and the starting rate was $.50 per hour. He later worked for Lockheed, Goodyear Arizona, Kellett, Hiller, and Cadillac Motor Car.

Paul Becka at N564A controls and Webb Scheutzow; Test run-up at “International Headquarters” January 1963.

His experience includes lofting, jig building, process engineering, preliminary design, mechanical design and staff engineer over prototype construction and test departments. In the course of the years he made contributions to the DC-3, A-20, Vega Ventura, PB2Y3, PB4Y3, PV-2, B-24, XR8, XR10, UH12 (H23) and Cadillac military vehicles, M41, M42, M56 and M141.

Starting his own company in 1964, he has built on the patents and concepts proven in the original Model B, N-564A, test bed, which was designed, built and flown under the FAA Homebuilder’s Regulations and now has the 180 h.p. production Model B in the final stages of Type Certification.

SCHEUTZOW BEE PRELUDE

Before we get on with our discussion of the Scheutzow BEE, I would like to point up some of the background leading to this undertaking. My true and loyal wife Marjorie and I had made several moves; from Santa Monica, my wife’s home, to Phoenix, to Philadelphia, and then to Palo Alto in July 1946.

In the course of our travels we also brought our first two children into the world. In 1946 Christine was two years old and Jan was eight months. I am amazed that in five years we undertook so much; however, it seemed commonplace then.

This period in our country’s history was one of great turmoil; we were all engaged in an intense struggle. I am reminded of this by the current TV presentation of “World at War.”

Whole nations disappeared almost overnight, others were driven to the brink of destruction. Hitler and his legions were a formidable opponent, at the same time we were engaged almost alone in the massive Japanese War of the Pacific.

In July of 1946 the war was over, we moved to Palo Alto to join the helicopter team being assembled by the young Stan Hiller in the company he at first named “United Helicopter Corporation.”

A remarkable amount of talent was to be found in this group; Wayne Wiesner, Bob Wagner and Jim Rigby from Kellett Aircraft; Joe Stuart III from Aeroproducts, Don Jacoby from NACA, and Frank Peterson one of the first helicopter pilots trained at Wright Field in the Sikorsky R4.

Instrument panel, cyclic and collective controls. Forward fuselage was constructed of aluminum tubing.

The state of the helicopter art is reflected in a humorous way by a remark of Peterson’s. He said of his military flying, “Everytime I crashed I got a promotion.” A most unusual person in the Hiller group was Frank Coffin who had been taught to fly by the Wright brothers.

With the dramatic decline of the aviation industry immediately after the war, much talent was available. There were many other able and experienced people in that early group.

After certification of the Hiller UH-12 (Army H-23) was completed, in April of 1950 we moved east to the wide open spaces of Ohio. The beginning of the Korean War in June of 1950 brought me into the Cadillac Motor Car, Cleveland Tank Plant.

Eleven years of highly varied experience in the design, testing and development of military track-laying vehicles followed. In June of 1961 I resigned from the Cadillac organization to begin the development of my concepts of a lower cost helicopter.

With some misgivings, my wife agreed to this radical change. By this time our family had grown to four children. Christine would be entering Valparaiso University in 1961, Jan would be off to Princeton in 1963, Paul and Mark both in grade school.

SCHEUTZOW MODEL B DEVELOPMENT

As with any aircraft project, the engine decision is the first order of business. In this instance it didn’t quite work that way. I was able to purchase surplus McCulloch MC-4 metal helicopter blades from an Army project at Ft. Benning, and matched these with a 90 h.p. Continental.

While these components would build a relatively small helicopter in a two-blade configuration, this was preferable to starting by building my own blades. Wood blades could have been made, but they are not as dimensionally stable as metal blades.

The weight of mechanical transmissions required in a helicopter, plus engine weight tends to place minimum practical limits on the engine size that can be used. The 90 h.p. chosen was convenient, but a mite small.

In making a helicopter engine selection I would not consider anything less than an honest 125 h.p. I would certainly choose a proven, reliable aircraft engine above any other type of powerplant.

In designing the transmission, rotor hub and control system, I found a way to integrate these components into a single unit. This component also fitted in nicely with my desire to set up a general arrangement which would permit servicing any one major component without having to remove or disassemble any adjacent one.

I started out with a strong preference for a gear transmission, but on closer study found that the advent of Polyester cord in the construction of V belts had produced a large gain in both capacity and reliability. I used twelve “3V” type belts on N-564A and never had occasion to give the transmission a second thought.

We did use individual tachometers for the rotor and engine, and while a dual tachometer is typical in helicopters and would be required by FAA regulations, the pilots found no problems in using individual tachometers. The tail rotor drive system on N-564A is of interest. I had a lot of experience in military vehicle hydraulic gun control systems.

Vickers pump and motor components are relatively easily found in the surplus market, so I designed a hydraulic tail rotor drive system using these components. At first this looked like a good way to overcome tail rotor drive mounting problems. This taught me quite a bit about tail rotors.

The main rotor of a helicopter can only obtain the amount of power available in the engine, a relatively small percentage of the power it could absorb. By comparison, the tail rotor can demand an almost unlimited amount of power right up to stall. The hydraulic drive was undersized, and to size it properly would have been excessive in weight.

The long belt runs were a convenient fix. However, while they performed O.K., they were a constant concern because they could easily develop standing waves on the slack side. The long belts were not really a good idea.

Centrifugal clutch, over-running clutch, tail rotor hydraulic pump, and cooling drive a-la-Corvair. Corvair centrifugal blower and shroud were also adapted. Continental 0-200 engine was modified to run in the vertical mounting.

The tail rotor blades were mounted on a flexural, laminated steel strap hub arrangement which eliminated the requirement for bearings. We used this arrangement successfully and I believe it has since been developed in more sophisticated form in other applications.

The fuselage design consideration was made on the basis of ease of construction and convenience, and therefore welded tubing was chosen, using experienced and established welding sources. The helicopter landing gear chosen was the old established skid type. This has a lot of advantages; it’s simple, stable, relatively lightweight and will absorb some abuse.

One of its attractive qualities is that when you are running the helicopter on the ground there is very little tendency for the helicopter to move out of place. However, ground handling procedures with skids are a bit of a nuisance.

There are some advantages to wheel landing gear, and in the larger new high performance helicopters being designed, retractable wheels are now coming back into use.

N564A Tail Rotor with original hydraulic drive system.

Be the first to comment on "The Story Of The Scheutzow Bee"