Single Seat Scorpion One Kit Built Helicopter

OneUpmanShip

ARTICLE DATE: February 1971

First off, this pilot report is by “remote control” since Scorpion helicopters, more than favorite putting irons, handkerchiefs and maybe wives, are not for sharing. Affidavit your umpteen thousand hours of rotary-wing time, and the inevitable rebuff to your request to fly somebody’s one-man Scorpion will be: “You build it; you fly it.”

This would seem to betray a certain misgiving about the handling qualities of this tiniest of helicopters. And indeed, one Scorpion owner does tell about the high-time chopper pilot who climbed into his machine, pulled it into a hover and transformed the entire works into instant spaghetti by squeezing rudder the wrong way.

Nevertheless, no one has yet disproved the rotary-wing homily that the smaller the helicopter, the more jittery it will be to fly. As perhaps the world’s smallest helicopter, the Scorpion personal helicopter, therefore, would seem to qualify as the world’s trickiest.

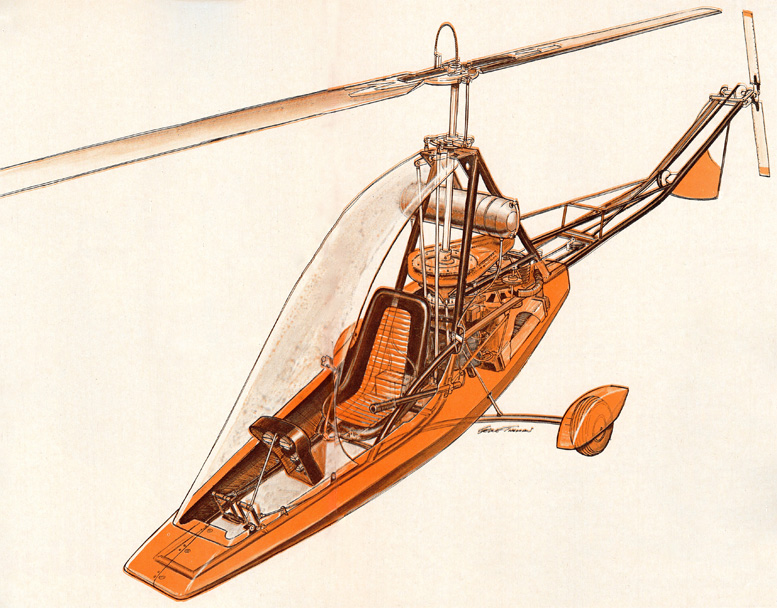

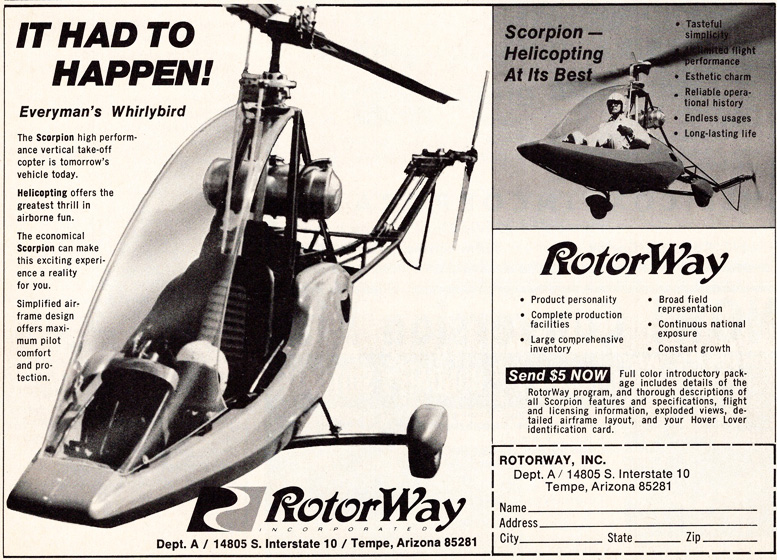

The Scorpion personal helicopter qualifies as a true, full-hovering helicopter, not an autogyro. There are two body styles: this one with a large canoe-like fiber-glass sheath, and also a conventional skid gear version with a smaller plastic nose section, as above.

Confront Mr. B. J. Schramm with this observation, and if he has a Scorpion within reach, he may render you dizzy with his repertoire of zooms, swoops, quick-stops, and autorotations. Of course, tightrope walking over Niagara Falls might seem easy for someone who has cultivated this skill assiduously, so that’s no real proof.

But Mr. Schramm, president of Rotor Way, Inc., is willing to talk turkey. The control sensitivity of his 475-pound helicopter, he claims, is less “nervous” than that of a Brantly (which is damnably skittery), and slightly better than that of a Hughes 269 (slightly less damnably skittery).

Furthermore, says he, the Scorpion autorotates as well as or better than the Hughes. And that’s something a chopper pilot can relate to.

In other ways, however, Mr. Schramm holds unorthodox views about the rotary-wing business.

He figures a guy can not only build his own helicopter; he can teach himself to fly it. And to follow through on this idea, he’s developed an enterprise of no little magnitude, backed by a shiny new factory in the desert outside Phoenix, Arizona, plus the handsomest little $6,178 one-man helicopter ever to stir up dust, and an elaborate program of do-it-yourself construction and self-applied rotary-wing flight indoctrination.

The rotor blades have a steel leading edge, with an aluminum trailing edge bonded and screwed to a birch main spar. The airframe is made of tubular steel pre-bent at the factory. A five-gallon tank is mounted behind the rotor mast.

The tail rotor is driven by V-belt. Another set of six V-belts transfers power from the engine to a counter shaft with a clutch for autorotations. A second stage is reduction configured with a chain drive, thus eliminating conventional gear boxes and tail rotor shaft drives.

The helicopter itself represents a bundle of surprises and innovations. Practically everything is belt driven, including the main rotor and the tail rotor, eliminating gear boxes and shaft drives. Part of the reduction sequence, however, employs a chain drive in the power train to the main rotor. The engine has perhaps the most unexpected heritage.

It’s a two-cycle, V-4, 115-hp Evinrude outboard motor called a Vulcan. According to Schramm, it is nicely suited to high-throttle running conditions, and its water cooling provides a greater margin of engine heat dissipation in hover operations than the conventional air-cooled aircraft powerplant.

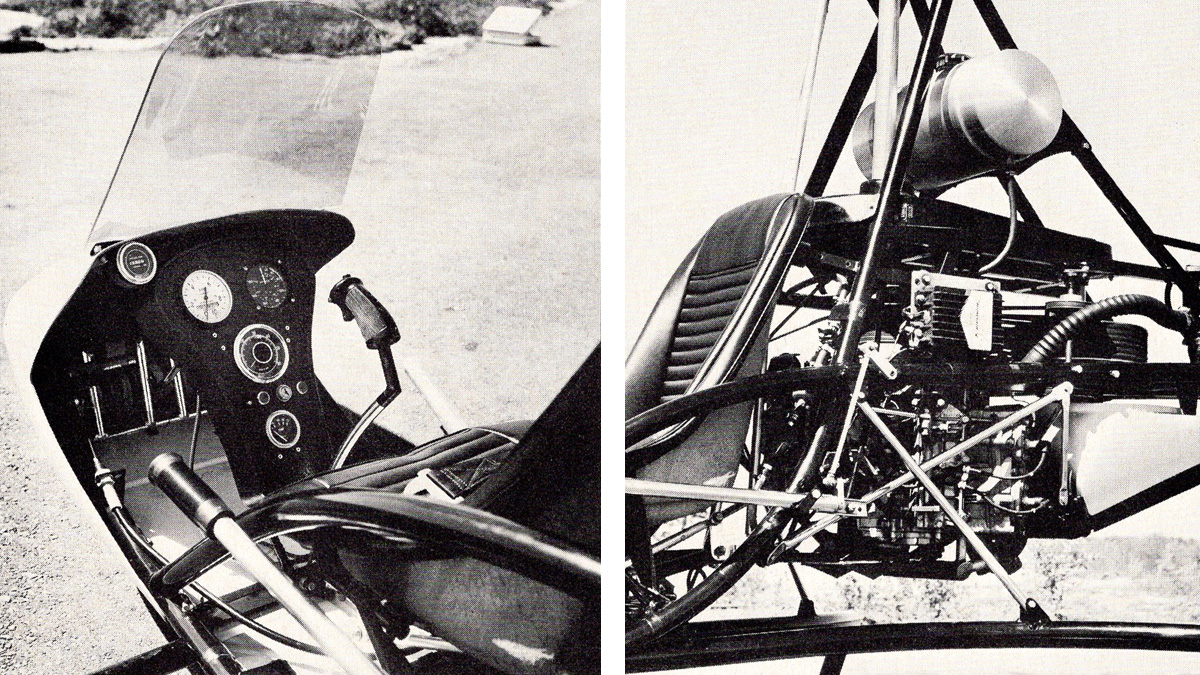

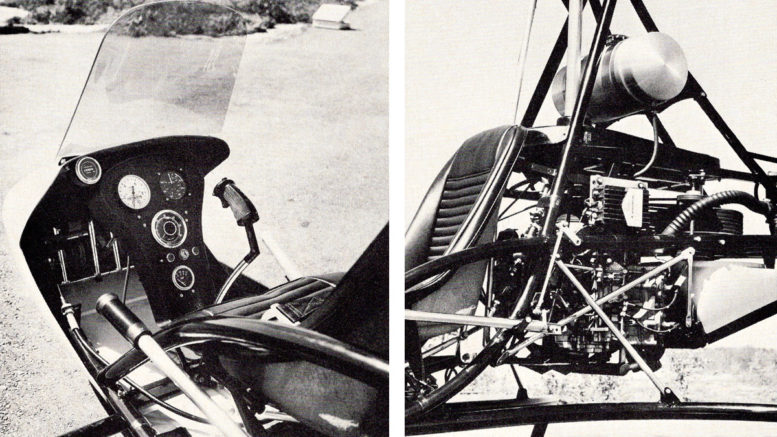

In the Scorpion, cyclic and collective controls for changing the tilt of the main rotor disc and the pitch of the teetering blades are separate and distinct. A unique flexible push-pull cable sprouting up through the rotor hub handles collective pitch.

If the rotor system is different, it is also, according to Schramm, tough and trustworthy. “It is unbelievable what this rotor system will take. No other is designed to such high safety standards.” But then the entire machine is designed for the amateur.

“There are enough built-in tolerances so that no catastrophic errors can occur,” says Schramm, who with partner Bob Everts began developing the machine about 12 years ago. Along the way, they devised not only a unique hunk of hardware, but a program to introduce the very tricky business of helicopter piloting to the uninitiated.

Why not just tell the fellow to go out and learn to fly in some two-seater with a flight instructor in the conventional way? Because it costs $85 to $125 a gosh-durned hour — that’s why. But Mr. Homebuilder doesn’t simply hop into his newly finished Scorpion and tackle hovering autorotations.

The engine is a 115-hp outboard two-stroke with four cylinders in V-configuration. A ducted fan provides forced cooling of the water-cooled engine even during hover.

The loop at the top of the rotor mast is a push-pull cable, which changes blade pitch according to up-and-down movement of the collective in the pilot’s left hand. A motorcycle-type twist grip on the collective operates as a throttle, in conventional fashion, although the rotor blade turns in the opposite direction to most U.S. helicopters.

This calls for reversed rudder movements with collective pitch changes. Although the rotorcraft comes in kits with many precision parts finished, a considerable amount of home shop work remains to be done, including welding and cutting of brackets from sheet metal.

The factory holds him by the hand every inch of the way. Once the helicopter is ready for flight, Mr. Schramm himself will come out and inspect the machine (for the price of a one-way airline ticket), and fly it to see that everything’s in running order.

Then the factory program insists that the Scorpion be tied securely to the ground by each landing skid corner while the novice teaches himself to hover, limited by the tethers to not more than a few inches above the ground.

Smile, but don’t fly: no rotor. In this configuration a high, curving wind visor is available. Completely enclosed cockpits are also under design.

In little 5- and 10-minute increments, the embryonic pilot gains enough skill and confidence to cut the tether one day and attempt free hovering exercises.

And somewhere along the way before he attempts climbs, cruises, landing approaches, and engine-out autorotations, he is advised to go get those hours of dual instruction that he can’t do without. How well does the Scorpion actually handle through a boot-strap program like this one?

Builders we talked to say the idea seems to work. Some report that the helicopter works flawlessly and with unbelievable lack of vibration—after careful tuning and adjustment. Others report a bit of cyclic stick shake.

When properly adjusted and balanced, the Scorpion flies smoothly and with a minimum of vibration. Although component “lifetimes” are not computed and listed as with conventionally manufactured and certificated helicopters, designer Schramm maintains the rotorcraft is built with broad strength margins.

The one-man ship must be checked off by an FAA inspector under the experimental category, and the flyer must have a regular pilot’s license.

Some had trouble adjusting drive belt tension, and blew out a couple of sets of belts until they resolved the matter. And a continual upgrading program sends along occasional modifications from the factory.

At any rate, all the precision components come pre-finished, and the basement mechanic can buy things in financially digestible lumps, one at a time if he pleases. It takes about 600 man hours to construct the Scorpion, or six to eight months in spare time, evenings and weekends.

The Scorpion will hover, quick stop, do autorotations, and cruise at up to 70 mph. For the novice flyer, there is a beginner’s program of self-instruction, aimed at paring hours of expensive dual lessons.

No particular expertise is required (except a certain handcrafting talent and welding—though this can be farmed out), and since the aircraft comes under the Experimental category, it must be checked over by an FAA inspector.

Granted, the final result won’t have the conventional manufacturer’s suggested component lifetime limits. As one homebuilder explained it, “That’s something of a grey area.” But he figured that if Schramm has been flying them around for 12 years or so, “they must be pretty well proven.”

Be the first to comment on "World’s First Personal Helicopter"