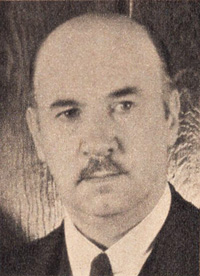

By Igor Sikorsky – as told to George Daniels

Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky – May 25, 1889 – October 26, 1972), was a Russian-American aviation pioneer in both helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft. His first success came with the S-2, the second aircraft of his design and construction.

His fifth airplane, the S-5, won him national recognition as well as F.A.I. license number 64. His S-6-A received the highest award at the 1912 Moscow Aviation Exhibition, and in the fall of that year the aircraft won for its young designer, builder and pilot first prize in the military competition at Saint Petersburg.

After immigrating to the United States in 1919, Sikorsky founded the Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation in 1923, and developed the first of Pan American Airways’ ocean-conquering flying boats in the 1930s.

In 1939, Sikorsky designed and flew the Vought-Sikorsky VS-300, the first viable American helicopter, which pioneered the rotor configuration used by most helicopters today. Sikorsky modified the design into the Sikorsky R-4, which became the world’s first mass-produced helicopter in 1942.

Licensed helicopter pilot No.1, designer Sikorsky enjoys the thrill and the experience of personally flying his amazing wingless aircraft.

He has flown these ships in scores of experimental hops, and also set the world’s sustained flight record for helicopters, yet neither he nor any of his test pilots has ever so much as scratched a finger in a helicopter.

When he says they’re safe, he means it.

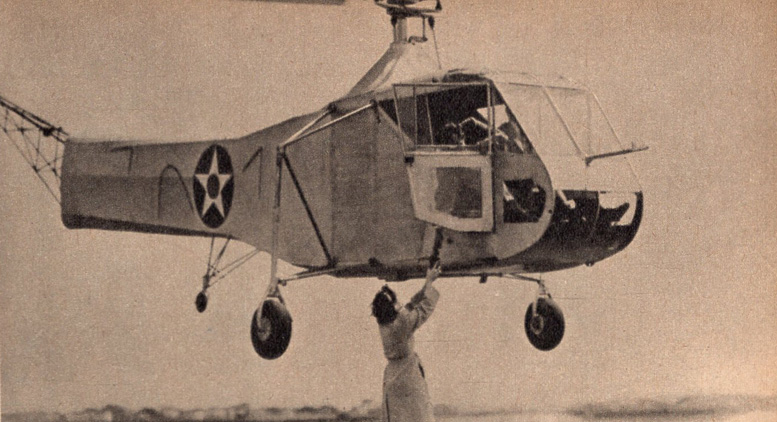

Latest thing released in helicopters

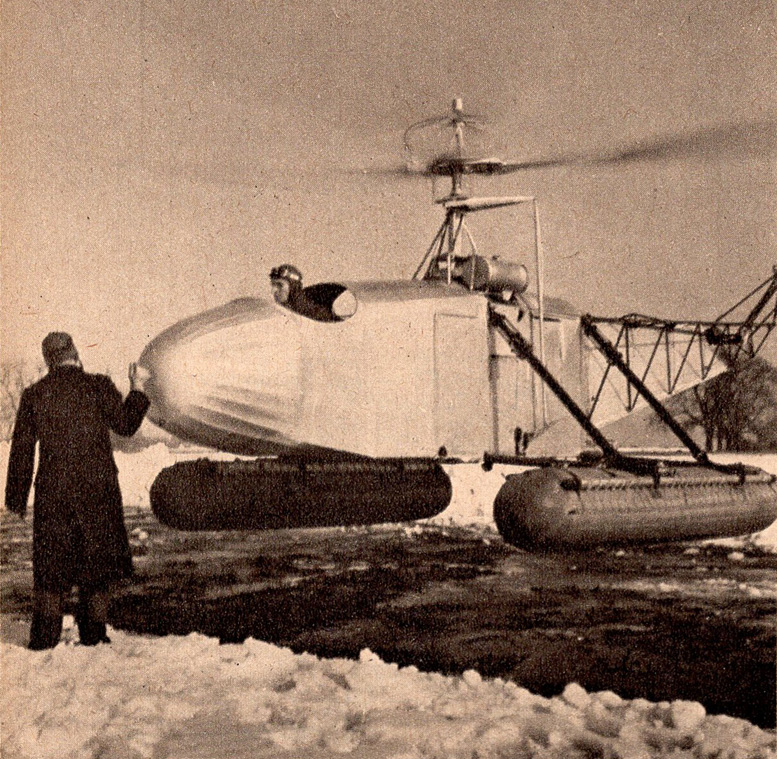

is this Sikorsky-bullt Army ship. Main rotor is approximately 36 feet in diameter, steering rotor at tail, about 7.5ft. Like its smaller sister ship, it can fly in any direction, including straight up and straight down. Army may use this type of ship for message carrying and ambulance work. Rough-sea rescues might be made by rope ladder as shown while ship hovers.

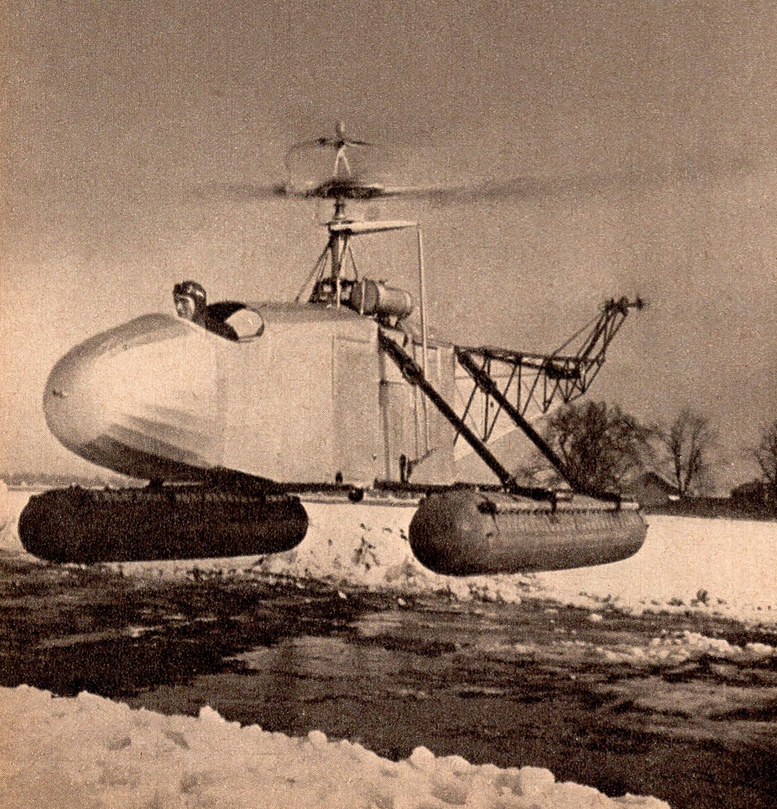

Your family helicopter is no longer an idle dream, for what may well be the direct forerunner of the “heli-flivver” is already flying. The present ship is a 100 horsepower ship, with optional installation of conventional wheel-type undercarriage, or pneumatic rubber pontoons that enable it to take off or alight on either land or water, or even on mud, snow or ice.

As a result of recent improvements, it is doing the things today that the private owner or commercial pilot of tomorrow will want his ship to do, and it is doing them safely and economically.

A mere touch of a lever whisks you straight up into the- sky in this ship, a slight movement of a control sends you scurrying across the countryside. And all the while you know that the patchwork view below contains a thousand airports—for you can land safely almost anywhere.

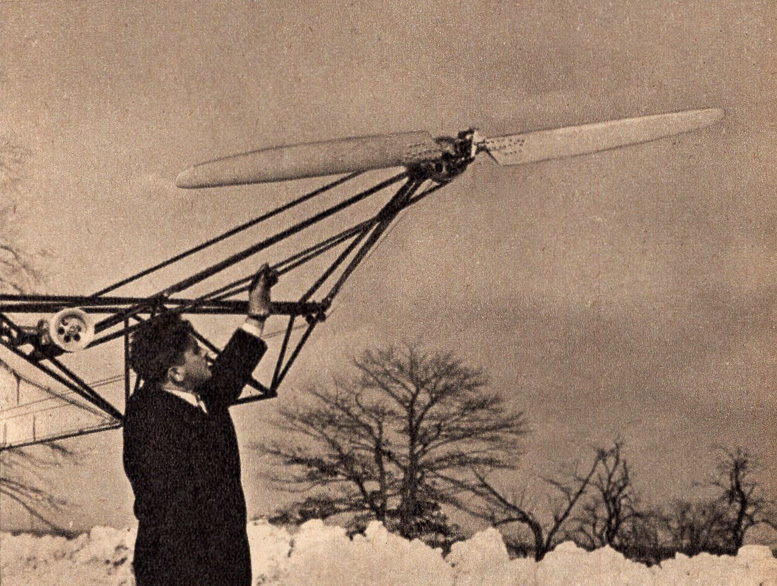

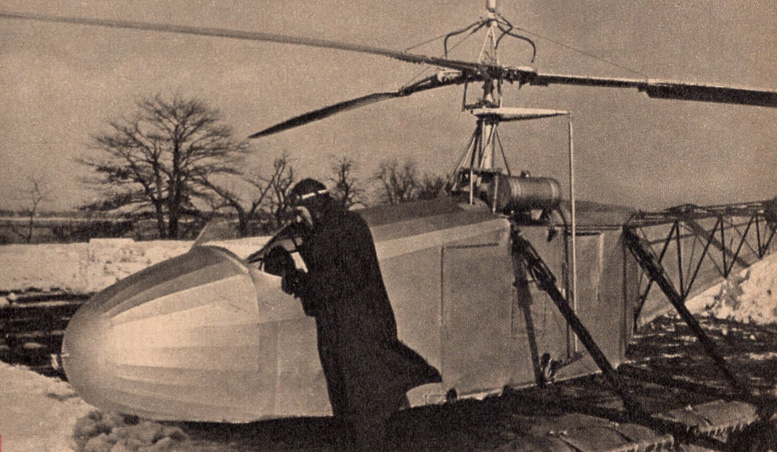

Patent Engineer V. Roxor Short points to rudder propeller. This steers helicopter by pulling tail to right or left when corresponding rudder pedal is pushed to vary pitch.

This ability of the helicopter to land where other types of aircraft cannot, makes it useful for a wide variety of purposes. The new Army helicopter, for example, has not only hovered stationary in mid-air, but has also shown that a man can safety descend from it on a rope ladder.

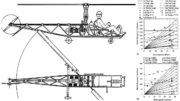

In its original form the experimental ship carried three 46-inch radius propellers at the tail for control. One propeller faced sideways as at present, for steering, and the other two faced upwards at the ends of outriggers on each side. All three had variable pitch blades, controllable by the control stick in the cockpit.

When the stick was pushed forward, the two propellers which faced upwards were readjusted to pull upwards, lifting the tail, and depressing the nose. This caused the ship to move forward. The reverse movement of the control stick caused an opposite effect and produced a backward motion of the ship.

Pushing the stick to either side caused the tail propeller on that side to pull downward while its mate on the opposite side pulled upward, causing the ship to tilt in the direction the control stick was moved.

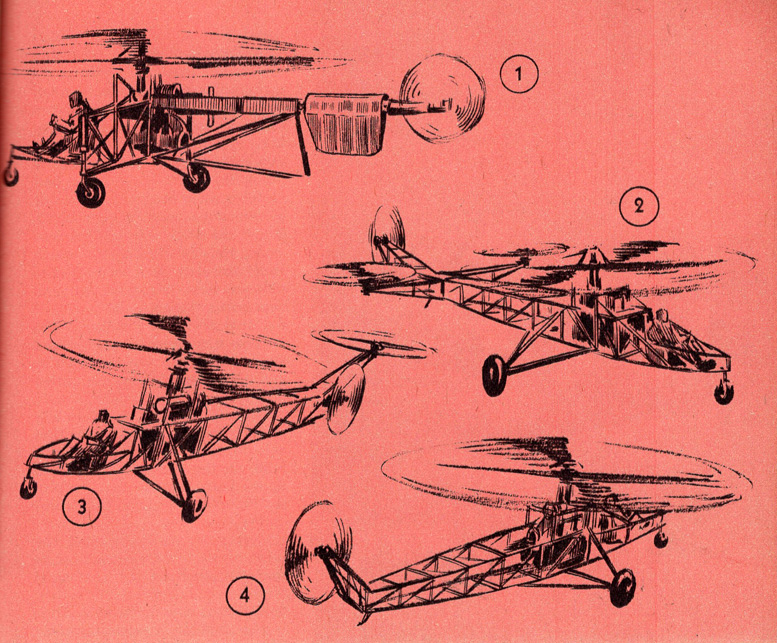

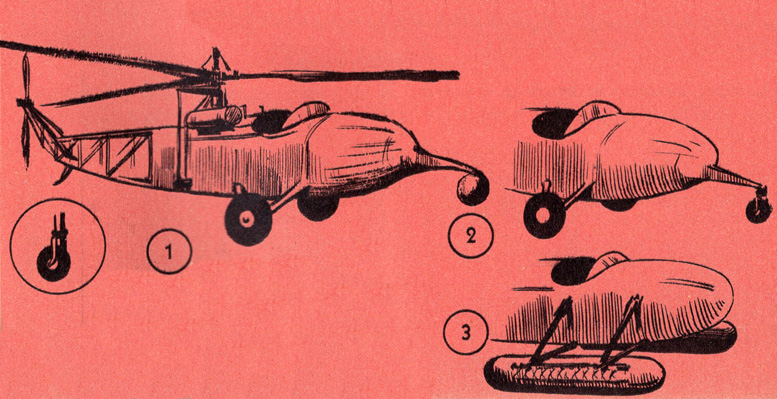

Ship No. 1 was first successful Sikorsky helicopter. Controls were on same principle as those now used. Pilots and engineers lacked experience, so tried types 2 and 3 before returning to original idea (4). Modern fuselage eliminates tail fin.

During the summer of 1941, the main lifting rotor was changed so that the pitch of the individual blades could be varied as they passed each side of the ship. Thus it was possible to cause the main lifting rotor to tilt sideways, controlling the craft in roll and eliminating the need for the two horizontal outriggers at the tail.

In their place, one horizontal tail propeller was mounted directly above the tail of the fuselage, facing upwards, and the steering propeller facing sideways at the tail remained as before. The tail propeller which faced upward, lifted or depressed the tail as the stick was moved forward or backward respectively.

The side propeller continued to act as a rudder, pulling the tail to the left or right when the corresponding rudder pedal was pressed. The next step in the refinement of the helicopter consisted of redesigning the main rotor pitch control so that the pitch of each individual blade could be varied throughout its entire circuit.

Thus, if the pilot wished to point the nose of the ship down, he would move the stick forward as usual, but the controlling effect came from the main rotor. By feathering the blades in their cycle, each blade could, for example be made to decrease pitch as it passed the front of the ship, and to increase pitch as it passed over the tail.

This would tilt the rotor forward and cause the ship to tilt forward and if continued for a short time to actually move forward. This system of cyclical pitch control has been found excellently satisfactory, and is the type now used on the test ship.

The takeoff. Engineer rests hand on helicopter’s nose as ship rises slowly, to demonstrate perfect control. Wind is about 20 m.p.h.

Only one rotor in addition to the main one is needed with this arrangement and that one faces sideways at the tail to act as a rudder. Less complex than your automobile, the private helicopter will lend itself easily to production when the time comes, special purpose ships doubtless being among the first civilian machines to serve the public.

It is not difficult to see how the helicopter-ambulance, for example, could perform invaluable work in otherwise hopeless instances. It could land and take off without danger in the soft mud of flooded in the deep snow of an areas, or isolated forest clearing. Even the roof of a mountain cabin is an airport for a helicopter.

In air mail use, the helicopter could speed the step between mail plane and post office by carrying the mail directly from the airport to post offices in central areas of towns and cities.

Hovering over its parking space after takeoff, the ship prepares to back away from Ml camera.

Landings would not be essential, along these aerial mail routes, as today’s experimental helicopter has already demonstrated its ability to pick up or deliver articles while hovering in mid-air. However, it is difficult to conceive of a post-office, on or near which a helicopter could not be landed.

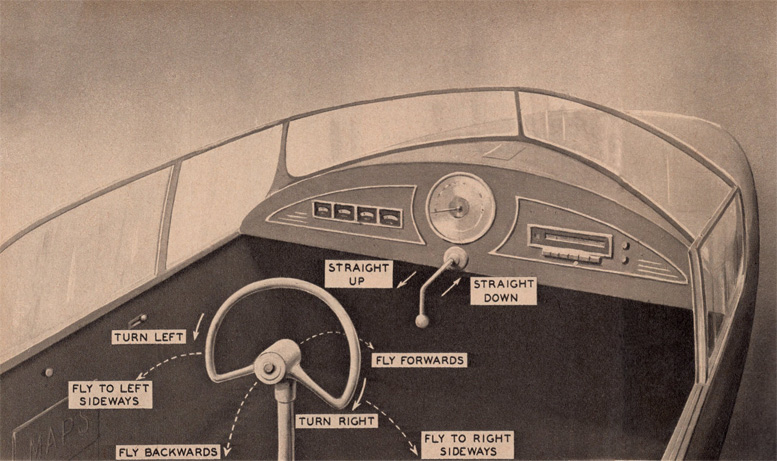

The controls of the helicopter are simple and easy to master, being practically the same as those of an ordinary sport plane. Perhaps the chief difference lies in a lever beside the seat called the “main pitch control lever”. You pull it back—and the ship rises straight up. By using the other controls simultaneously, you can rise at any desired angle.

Perhaps one of the effects of the general use of private helicopters will be that of developing residential areas far from business centers. The healthful atmosphere of a lofty mountain retreat can easily be the home environment of the commuting business man.

Helicopter backs out of landing area at walking pace, under perfect control – despite rising winds which blew the camera tripod over a moment after this picture was taken.

A hundred mile trip to work is only an hour’s ride in a helicopter, and you needn’t wonder how you’ll get to the office if the weather happens to be foggy. Your helicopter can take off or land vertically as slowly as one mile an hour, or less if need be.

It can travel forwards or backwards at an equally low rate of speed, or even sideways when the occasion demands. Once in the air, a few simple navigation instruments will suffice to take you to your destination regardless of visibility, for it is always possible to descend at a snail’s pace to check your location by road signs if you’re in doubt.

If for any reason, it should become necessary to land in a strange area, you have the assurance that your ship can come in even with a dead engine, at practically walking speed. It is not by any means limited to vertical ascent or descent, however, for the helicopter can glide in any direction with or without power.

Climbing straight up a little higher, as the pilot smiles down to the camera. The helicopter is no noisier than a light sport plane. The main rotor makes a swishing sound.

If your engine should fail, it is a simple matter to glide toward a desired landing spot (which may be a very limited space) and then settle the short distance into it vertically.

With your engine running you can spend as much time as you need in landing, backing up or shifting sideways to park in a tight spot. Unlike conventional aircraft, in conditions of poor visibility the appearance of an obstruction ahead during a landing glide is little cause for alarm.

You can bring your helicopter to a full stop in mid-air, then climb straight up, settle straight down, or move in any other direction you may care to—as slowly as you please. If your ship is an amphibian, which may very likely be the case, you need not worry about lowering the wheels for a ground landing—or forgetting to retract them when descending on the water.

Artist’s version of future helicopter cabin. This control system would eliminate rudder pedals used on today’s ship. Airplane pilots prefer rudder pedals, auto drivers may like their airflivvers with wheel and perhaps a throttle they can “step on. “

The helicopter amphibian needs no wheels, and even today lands and takes off easily from either water or land even under heavy wind conditions that would seriously hamper a conventional ship of the same weight. The helicopter will not replace the airplane as a means of long range high-speed transportation of heavy loads.

A reasonable limit to the capacity of helicopters of the type now in operation would appear to be in the neighborhood of 12-15 passengers or their equivalent in freight. A logical top speed will probably be around 140-150 miles an hour, although this may not be attained for several years.

While the pilot beside him leisurely holds the ship stationery in midair, the passenger of Army-Sikorsky helicopter opens door and receives a package from the girl on the ground.

Their utility, therefore, will be in the short run, the aircraft feeder line, the private flier, and any type of flying that must be done in and out of small areas. While the helicopter cannot equal the range and speed of the conventional airplane, it can provide safe and practical air transportation to and from places where no other type of aircraft could possibly operate.

Chief Pilot Charles L. Morris prepares for a hop in the daddy of heli-flivvers. He holds helicopter license. No. 2 Rotor control rod is visible on the fuselage side behind the cockpit.

The first two helicopter licenses have already been issued, and it is logical to assume that the ease of operation of the helicopter will make the requirements for this type of license much simpler than those for any previous type.

As to the possibility of overly heavy helicopter traffic, it is only necessary to consider the comparative useable areas of the highways of the world and the sky overhead. The vast “Helicopter highways” offer not millions, but billions of times the useable space.

This little known helicopter was Sikorsky’s first successful one. It had the same type of control system as that used on the present day machines. Pilots and engineers lacked experience, however, and tried numerous other control arrangements before returning to the original. Vertical fin on its tail is absent on the modern helicopter as the side area of fuselage has a similar effect.

The helicopter will not be confined to one narrow pathway, or even to one level, but will have millions upon millions of cubic miles at its disposal. Heavily populated areas or other traffic centers will naturally have some form of traffic control just as airports have today, but the helicopter flier need have no worry over a crowded sky.

Beginners will doubtless behave much like the new automobile driver—poking along the skyway at 15 or 20, but they won’t get in your way because they’ll be flying at their own altitude level. The speed demon, too, will fortunately be confined on his own particular level, where he won’t be distracting your attention if you prefer to loll along and enjoy the view.

Artist’s sketches of some of the varied landing gear systems that have been used on the helicopter. Wheel and skid combinations, rubber nose “bumpers,” and the present day rubber amphibian “feet” have all been successful in operation.

Be the first to comment on "You Can Fly My Helicopter"